Based on a True Story

Hardcore's spirit and ethos has been passed down across multiple generations and over various mediums. But at its core, ours is an oral tradition.

I.

A little over ten years ago, when I was teaching at a university in Brooklyn, I was asked to design and implement a required course for all Communications majors that would give students an overview of our three predominant eras of using language: Orality (the culture and form of narrative that existed before the invention of writing), Literacy (the culture and organization of ideas that developed with the invention of writing), and Secondary Orality (the culture and ways of thinking that materialized after the invention of mass printing, and then again, with the internet). A study of these eras, as far as the course went, would go on to show that meaning is not solely confined to the unembellished words we use to tell our stories, but can be embedded into the very mediums we use for language themselves. In other words, how you transmit culture is as meaningful as the actual content you attempt to put forth.

In the case of pre-writing cultures, storytelling played a unique and integral function. Whereas the print and digital ages have been able to create a semi-permanent record of its people’s cultural history, traditions, and beliefs via the written word—with difficult-to-remember details and comprehensive lists that could only be documented with this new “technology”—purely oral cultures had no choice but to transform the spoken narrative into a more basic kind of record-keeping vehicle. And because valuable information needed to be both stored and retrieved in this narrative form, the stories that emerged from such oral traditions needed to be somewhat easy to recall. That’s why whenever we hear stories that began as oral narratives—like, say, Homer’s The Odyssey—it’s still quite easy to find mnemonic devices, repetitive refrains, or other memory aids scattered throughout the text. These stories were made to be remembered, and the content reflects that reality of its medium—not the other way around.

A few weeks ago, in my praise of fanzines, I spoke about how these semi-permanent records have always “played an outsized role in the way we define and create hardcore culture”—and that’s true. We better understand the people who came before us because other people thought to write it down. But we can also take that idea back further. Because whenever I think about the transmission of hardcore’s history, traditions, and values, I still think about the stories and the storytellers—not necessarily the scribes. As such, whenever I interview people, I think about how I can best elicit and record a story that tells us something about the subject’s own unique experiences, because I know that, somewhere in that narrative, there is embedded data to be found—whether it be subtle information about the cities, the eras, and the conditions that created the kind of hardcore scene that these storytellers grew up in, or veritable lessons attached to our community’s history, traditions, and values. I also sometimes get the feeling that many of our best storytellers have told these stories several times before, or at least enough for these narratives to have been hewn into a form that expresses everything they believe the story should reveal.

In this sense, I’d argue that hardcore is an inherently oral tradition. Telling each other stories is how we transmitted our culture before the proliferation of fanzines and blogs. And we told our stories repeatedly so that they might be remembered.

II.

Since relaunching Anti-Matter last year, I’ve recorded over 50 new interviews. Many of them, I’ve come to recently realize, are what I’d call “storyteller interviews.” Pat Flynn from Fiddlehead gave one of them. Brian McTernan from Be Well gave another one. Civ from Gorilla Biscuits absolutely gave one. There were others. All of them adhere to the tradition of hardcore that taught us that we can know ourselves by our stories. All of them adhere to the belief that the answers to most questions can be nestled inside of a narrative. When I sat down with Sammy Siegler, a hardcore lifer and legendary drummer who has played with an almost unthinkable number of bands—including Side by Side, Youth of Today, Project X, Judge, Shelter, CIV, Rival Schools, Glassjaw, and 7 Seconds, among others—I understood sooner than later that he, too, was a product of this hardcore oral tradition.

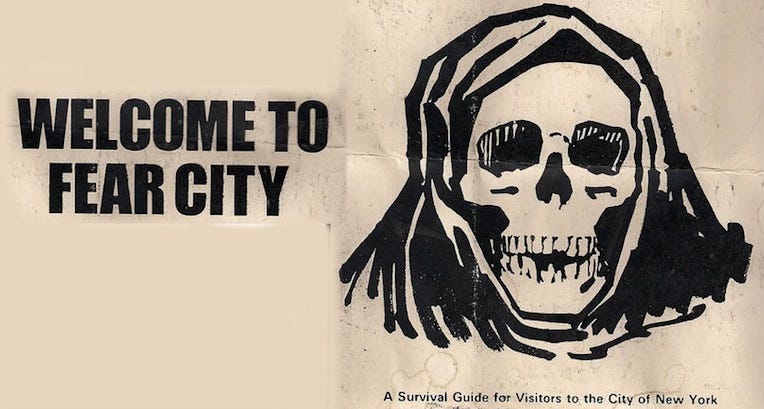

Of all the stories he told, however, there was one that I thought gave particular insight into both his own upbringing and the conditions that allowed an eleven-year-old kid like himself to enter into the New York hardcore scene of the 1980s—and how many of those conditions arose in the first place. In and of itself, this story has nothing to do with hardcore. But the embedded data is there. This story revolves around a man named Bernhard Goetz, who, in 1984, shot four teenagers that tried to rob him in a New York City subway car. After becoming nationally known as the “Subway Vigilante,” Goetz was eventually arrested, tried, and acquitted of attempted murder charges—being found guilty of only count of carrying an unlicensed firearm. But long before that decision came down, Goetz divided the city and became a cipher for America’s violent crime rates and gun laws. He was also Sam’s neighbor.

“There’s another story that really ties me to 15th Street,” Sam tells me, recalling the block in Manhattan where he grew up. “When I was nine years old, Bernhard Goetz lived right across the street from me. One day, after he got into trouble for shooting those kids in the subway, someone rang my buzzer and was like, ‘Hey, I’m from the New York Post. Do you mind if I take some photos from out of your window? I’ll pay you if I can take pictures of Bernhard Goetz.’ So I was like, sure. I needed a summer job; I needed money. And sure enough this guy paid me like a hundred bucks or something to hang out in my room and take pictures of Bernhard Goetz. But a couple of nights later, the sun goes down, and I see this little red laser scope coming through my window and onto the wall. And then my sister was in her room and she saw it, too. We came running out of our rooms like, ‘Oh my God!’ We really thought it was Bernhard Goetz. We thought he was pissed about us letting a photographer take pictures into his place. A lot of shit happened.”

On its face, this might be seen as a random, but ultimately terminal story, cast with a dash of New York City folklore. But thinking about my own history as a pre-teen kid who discovered hardcore in New York City, I understand that this story explains some of the things that I’ve had trouble explaining to out-of-towners who couldn’t understand how literal children like Sam and me became part of a scene that was older, difficult to penetrate, and occasionally, even somewhat violent.

For one thing, Sam was only eleven years old and home alone when he let a random photographer into his apartment. That’s not normal. (“My mom came home and she was like, ‘Sam, who’s that in your room?!’” he laughs.) But back then, there was a sense of fearlessness among New York City kids that’s difficult to describe today. Most of us were a part of the “latchkey kid” generation, and many of us, including Sam, grew up with extremely permissive parents—if we had parents at all. It would be at least two years, for example, before my father started asking me where I went every Sunday between 1987 and 1989. When I told him I was hanging out on the Bowery, he almost choked.

“That street is dangerous!” he said. But at no point did he ever forbid me from going back.

Even more telling, though, is the fact that Sam’s response to finding out that his neighbor was a mass shooter was almost startlingly indifferent. If that sounds wild to you, just consider the fact that New York was simply a more savage place in the 1980s. Growing up as kids in that decade, we never really had an expectation of safety anywhere. Young people were, to some degree, inoculated to the threats associated with urban living—and whatever violence we witnessed at New York hardcore shows still paled in comparison to the real-world violence that lurked literally everywhere else we went. Which is to say that this story, whether Sam realizes it or not, transmits a historical reality that’s worth preserving: It’s not that New York hardcore in the ‘80s was a violent culture. It’s that New York City in the ‘80s was a violent culture. Our community did not live inside of a bubble.

III.

The concept of storytelling has been slightly damaged, in my opinion, by a modern marketing and influencer culture that attaches its stories to “personal brands” and demands that its stories provide some type of cheap inspiration or immediate satisfaction; a narrative in the modern age only seems to work if it’s the length of an Instagram reel and if there’s a call-to-action that compels follower engagement.

Storytelling as part of an oral tradition is not so shortsighted. Hardcore stories are meant to be recalled over time. They are part of a wider fabric that weaves together generations and provides a sense of continuity to our ever-evolving scene. These stories also sometimes evolve alongside the people who keep them alive and under the circumstances with which they are told. Sometimes they help us relate to one another more, but often, they actually serve to explain why it feels like we can still be so different. Our only call-to-action is to listen to each other.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Sammy Siegler of Rival Schools, Youth of Today, CIV, Judge, and 7 Seconds.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is crucial to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

It's true, growing up in the 80's I was more scared about missing out on all the great things going on rather than the danger they presented. I grew up hearing about hardcore and all the great bands playing at the Living Room in Providence RI. Living in and going to college in Rhode Island, we were awed by the crazy in NYC and closer in Boston. I grew up with the members of Verbal Assault watching them them grow into a great band. With word of mouth and fanzines, we grew up with an oral history of hardcore history. I was never home, my parents had no idea where and who I was with. Going to hardcore shows, skateboarding around Newport RI, drinking and using drugs. Going to shows in Providence and Boston. I had a college friend who recognized Sammy on a record cover. He said "that's little Sammy, my brother is his wrestling coach in NYC." Great times but also bad times for the out of control of drinking and drugging.

That Bernie Goetz story is amazing, especially the part about Sam’s mom coming home and asking who was in his room. “Inoculation to the threats associated with urban living” is such an accurate description of what happens when you are immersed in it. I teach in Far Rockaway and an old friend recently asked me what Queens is like now, since leaving NY over 20 years ago. Initially I went into an explanation of all of the development and gentrification. Then as almost an afterthought I talked about the regular lockdowns my school has because of nearby stabbings and/or shootings. We even had to lockdown because someone released pitbulls into the school. There has been a police detail on the corner of my school for nearly a year. Naively I thought it was because NYC schools remain unlocked and open for anyone to just stroll right in, but just came to find out they are protecting a gang informant. This is the part of my job I never really think or talk about. The school building that my school is housed in is huge with students in K-8th grade. I guess the most immediate threat of violence we encounter with some regularity occurs when students get their parents involved in their fights. On more than one occasion I have had to act as a human shield bringing students to their buses as parents brawled in front of the school building.