In Conversation: Porcell

For the 30th anniversary of Anti-Matter this week, we're revisiting one of the best interviews ever from the original zine.

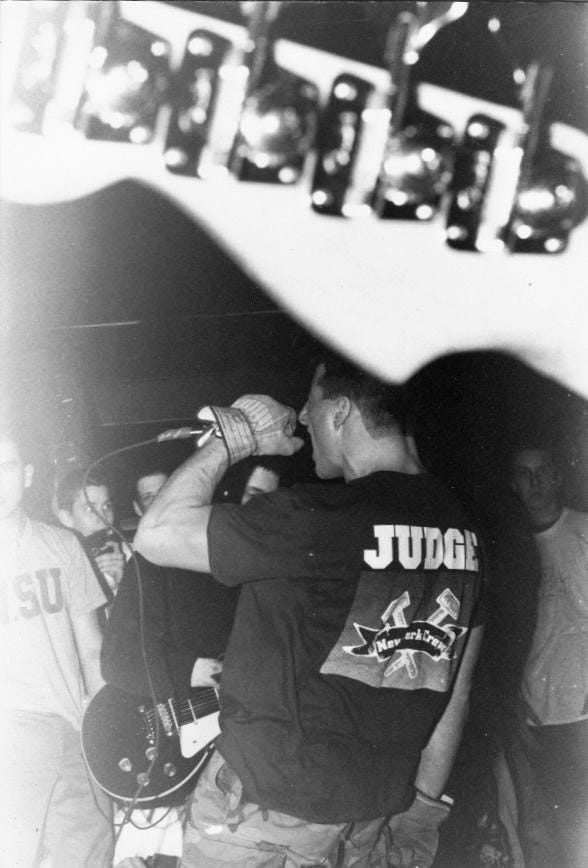

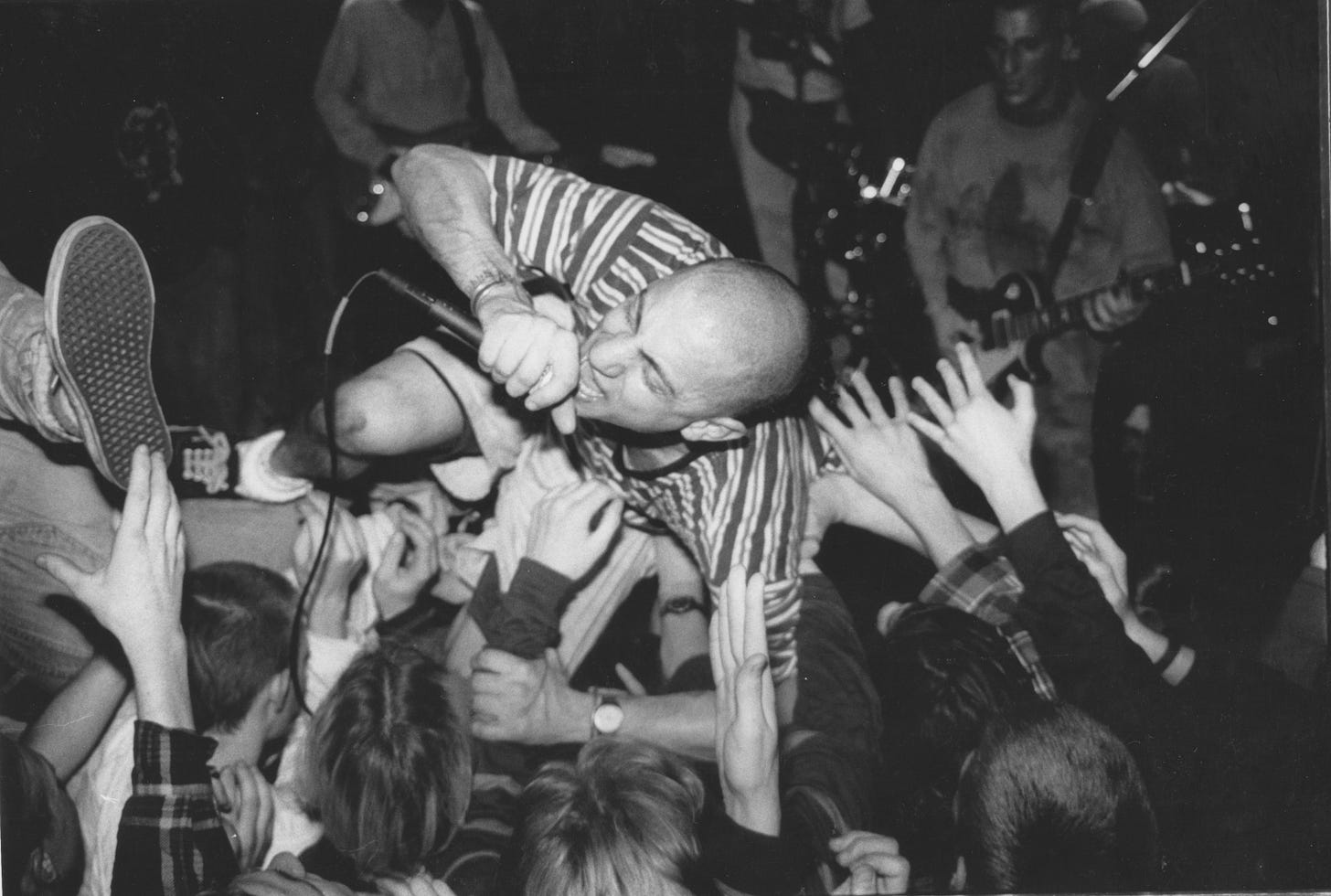

John Porcelly is best known as Porcell, the guitarist behind some of straightedge hardcore’s most seminal bands, including Youth of Today and Judge. His recorded tenure is coming up on forty years of music, and just last week he released his latest album, with a new band called Values Here. But things weren’t always so great.

Back in the early ‘90s, Porcell was a man in transition. By the time Youth of Today broke up in 1989, the band had launched straightedge as the biggest global movement hardcore had ever produced. But as the decade turned, so too did straightedge’s popularity, and Porcell was faced with a crisis of identity: What was a perennial man on a mission supposed to do when there was no longer a mission?

We originally recorded this conversation in my East Village apartment, in 1995, for the fourth issue of Anti-Matter. Porcell was settled on a new mission—as the guitar player for Shelter and a relatively new Hare Krishna devotee—so I felt like it was time to talk about that in-between period, the searching and the suffering and the fucking up. This interview wasn’t about getting Porcell to finally confess to “breaking his edge,” which he did, but ultimately, about acknowledging that rare period in the early ‘90s when many of us found ourselves thrust into the uncertainty of growing up amidst what was quickly becoming hardcore’s most radical evolution. We were opening up our record libraries, donating our Champion sweatshirts to Goodwill, and growing our hair out. We became either more permissive or more fundamentalist. We embraced violent gangs or joined peaceful cults. Vegans started eating meat and straightedge kids died of overdoses. Porcell’s story isn’t unique in that sense—and that was the point. We were all going through it.

Some may have chosen to judge Porcell harshly when this interview first came out 28 years ago, but in 2023, I believe it tells a more universal story about how so many of us choose hardcore as an identity, only to find out we still don’t know who we are. It’s a story about searching and being a searcher. As we commemorate the 30th anniversary of Anti-Matter, this felt like the perfect conversation to revisit.

PORCELL: [Lying on my bed] I feel like I’m on the psychiatrist couch and you're my psychiatrist. I’m so psyched for the Norm interview.

Don't think of it like that. I think the way our conversations go, it really doesn’t matter. They’re always interesting to me.

PORCELL: That's true.

So tell me about “The Big V.”

PORCELL: Anything specific?

He’s just such a mythical character to me. I’ve never seen him and I’ve never met him, but I feel like I know him. I feel like he's this 60-some-odd-year version of you.

PORCELL: No, no, no. This is the Big V’s deal. You gotta picture it. His name isn’t really Vito, but everyone calls him that because he looks like Vito from The Godfather [laughs]. He’s just this old, kinda-straight Italian guy; you know, the businessman who watches football games and eats lasagna. It’s kinda weird because my older brother is exactly like the Big V. Him and the Big V would play football and watch games on the weekend or whatever. I was always the black sheep. I was the punk rocker who shaved my head or dyed my hair. If you could just imagine me walking home with spiked blond hair to the Big V—it was such a comical thing. So it was always a battle in my house to see how far I could push it and how far the Big V could take it until he broke.

You wanna know something? The culmination of it all was the time when I was in college. He was always telling me that I had to go to college and I had to make something out of myself. He was almost counting on me to go to college because my brother was stupid in school and my sister wasn't really into it. But I always got good grades. He always said, “John, you're the one in this family who's going to make it. You're gonna make it.” It was almost like the Porcelly good name was resting on my shoulders. So he talked me into it and I went to college in Upstate New York. I really didn't want to be there. I mean, here we were. Youth Of Today had already started, hardcore was my life, Kevin Seconds was putting out our record. Things were happening. That was my meditation: hardcore. All the way through high school, all I ever dreamed about was being in a straightedge band and singing about things that I really believed in. But then the Big V sent me to college for a year and it was just the worst thing. I was the only straightedge person in the whole school. It was just weird. So at the end of the year, I didn’t even sign up for the next year. I didn’t register for my dorm or anything, and I didn't have the heart to tell the Big V. Anyway, I got this really hellish landscaping job for five dollars an hour. It was totally torturing work, shoveling rocks out of a dump truck all day long. The Big V thought I was saving money for school. He was like, “John, I'm so proud of you. You're saving up all this money for school!” But I couldn't live with myself; I had to tell him. Because not only was I not going to school, but Ray [Cappo] and I were going to move to New York City to get an apartment together. And the Big V hates New York City.

Finally, literally three days before I was supposed to go to college, I told him. It was the hardest thing I ever had to do in my life. Me and the Big V could never really communicate either, so that just made it harder. Anyway, I got up the courage and I walked downstairs and knocked on his door and walked in and said, “Dad, I gotta tell you something.” He knew it was serious. He was like, “What is it, son?” [laughs] I didn't know what to say, and I was just trying to break it easy. So I said, “Dad, I know you wanted me to go to college and everything, but I’m sorry. It’s just not what I want to do right now. I’m not going. And all that money I was saving up all summer long? I just spent the whole thing on a Marshall amp and guitar setup. And I’ve got something else to tell you. Instead of going to school, I’m going on tour in two days and when I get back, I’m moving out and I’m moving to New York City.” I thought he was going to go nuts on me. But he just stared at his paper for about 30 seconds of awkward silence and then looked at me straight in the eye—with almost tears in his eyes. He said, “John, I can't tell you how disappointed I am in you.” That was all he said. That was worse than anything he could’ve done. My father, my authority figure for my whole life, just came down on me like I was the biggest loser.

So when you got to New York, what was your first job?

PORCELL: Well, you see, when I first moved to New York I didn’t want to get a real job. My rent was only 150 dollars a month, so I figured I could just get a scrub job. I put up these housecleaning fliers that said: “Struggling art student trying to pay his way through college. Cleancut. Nice. Trustworthy” [laughs]. I had no idea. I just saw these fliers hanging up everywhere, all around the Village. Sure enough, I started getting all these people calling me up for ten dollars an hour to clean their houses. It was so weird because I would just go for the interview, and after fifteen minutes, these people would give me the keys to their house. I’d come in while they were at work.

After a while, Ray and I became pretty successful and we figured, “Hey. We could put up painting fliers and charge even more money!” Neither of us knew how to paint! It was so funny because we had to show references and we’d have all these fake references, like, “Jordan Cooper: Revelation Records” or “Duane: Some Records” [laughs]. The first painting job we got was this beautiful West Village apartment. It was totally an incredible brownstone with these beautiful wooden floors. She was going to pay us fifteen dollars an hour a piece. We were so psyched. So she left for work and we bought all this paint. It was so funny because Ray had this “How To Paint” book. And after we finished, we thought we did pretty good. We were like, “OK! Let's clean up!” So we lifted the dropcloth and realized we got the wrong kind. This lady’s beautiful wooden floors and apartment were soaked with paint. And when we started cleaning up, she came in and freaked out. She was like, “I'm not moving until you guys clean up every single spot.” It was like detention or something. I don't know, we had all sorts of weird jobs. I was never one to get a real job.

Why is that?

PORCELL: I’ve just never had to. I never really worked a job more than three months, anyway. That was another thing. We’d always get an apartment or get a job and then we’d go on tour. We knew it would be a temporary thing. Every single time I came home to New York I had a new apartment. It was an adventurous thing. We wanted to take over the world, you know?

Was that just you, though?

PORCELL: No. [Ray], too.

That's not what I meant [laughs]. I mean, for what it's worth, you and Ray are sometimes too much alike. And when you think about it, it’s been ten years since this move to New York.

PORCELL: It’s true. And I knew him way before Youth Of Today. I met him when I was like fifteen.

Is he like family now?

PORCELL: Yeah, I think so. After you’ve been with someone that long… I mean, the reason we get along so well is because we both really had these high ideals of what we wanted to do. When Youth Of Today first started, we had Graham [Phillips] and [Darren] Pesce in the band, and they weren’t that idealistic. Our whole idea was to put together our idealism and our music and put together a band that we could really rally behind. Our favorite bands always had messages: 7 Seconds, Minor Threat, Youth Brigade. We wanted to inspire people with music, and these other guys didn't have the same vision. We were willing to drop everything to do the band. Even today, we still have that same vision. So when you live with a person, you learn what makes him mad, grumpy, or happy. You learn what he’s really like as a person. But when you go on tour, it’s like a thousand times magnified. You’re practically living in a van with a person. It’s not like he’s in the next room or something; he’s sitting right next to you for months. And we’ve toured a lot, for years on end. It’s a real bonding experience. So since we’ve had so much history together, that keeps us together. It was weird when he first joined the Krishnas because we didn't see each other for years. I mean, I was on the first Shelter tour, but after that I’d only see him every now and then.

You mentioned something yesterday that I never knew before.

PORCELL: What?

Deprogramming Raghunath.

PORCELL: I'll tell you, man. When I first read that Maximum Rock’n’Roll thing [about the Hare Krishnas], it really upset the hell out of me [laughs]. It really did. I mean, when you live in New York and you grew up in the New York hardcore scene, the representative of Krishna wasn’t Romapada Swami and it wasn’t Dhanurdhara Swami. It was Harley. It was Richie Stig. It was John Bloodclot. So I always thought the Krishnas had a violent edge. Even though I used to go to the Greenwich Avenue programs and I thought that anti-materialism and vegetarianism were really cool, I never really trusted them. So when that came out, I was telling Walter [Schreifels], “Dude! We gotta deprogram Ray! We gotta get him back. He’s brainwashed!”

So why didn’t you do it?

PORCELL: We didn't have enough money [laughs].

That would’ve changed history.

PORCELL: That would have been hysterical.

Remember when you got back from that first Shelter tour and you started growing your hair out and it seemed like everybody was going through their own weird period?

PORCELL: Yeah. You know what it was? When the whole straightedge thing sorta fell apart… and it really did. I mean, the straightedge thing is back now, but after that tour it was really dead. It was almost an embarrassing thing to say you were still straightedge. And it was such a big part of my life that it really made me question a lot of things in my life. I was questioning the whole straightedge image, just thinking about how everything became cliché. Here was me—king of the cliché—with the Champion sweatshirt, crewcut, shorts. It was what I’d always worn, but now I was like the walking quintessential straightedge kid. And even though I dressed the same, I grew my hair out as a revolt at that sort of thing. It was a search for individuality. Everybody goes through it.

OK, then, this next question is optional [laughs]. Do you want to come clean on your own personal straightedge saga?

PORCELL: [Laughs] Oh, no! I knew it was coming!

Well?

PORCELL: Do you know?

I do.

PORCELL: God, should I come clean in Norm's zine? [Pauses] OK, I’ll do it.

Are you sure?

PORCELL: Yeah.

OK, then. The question I’ve been asked for years: Have you ever “lost your edge?”

PORCELL: It happens even to the best of us [laughs]. OK, OK. The first time I ever lost the edge… God. Well, when I was in high school, I went out with this girl for over two years. I was really in love with this girl. We never really broke up. We just went to college, and I always had this thing for her. So anyway, it was right in the Youth of Today heyday, and one day, out of the blue, she just called me up and wanted to hang out. So I saw her that weekend, and somehow she talked me into getting drunk with her. I felt so nervous at the time, but I did it. And it sucked, too, because Youth Of Today played CBs the next day. Let me tell you, when we were up there playing “Thinking Straight” and all those songs, I could’ve cried. Even though no one knew, I really felt like I let that whole crowd down.

Didn’t someone walk in?

PORCELL: I’m pretty sure it was Richie Birkenhead.

Did Ray know?

PORCELL: No way. I swore Richie to secrecy [laughs]. But I always figured that there was always nothing worse than a person who says something and doesn't practice what he preaches. In a way, I think it strengthened my straightedge. I’m not making excuses, but the fact that I just felt so bad and felt so much remorse about it… I was full-on hardcore straightedge after that. I didn’t smoke or drink or do anything.

The next time I broke my edge was way after Youth Of Today broke up and way after Judge broke up. It was right after I moved back from California to New York. It was such a weird time in my life. I wasn’t starting to get into Krishna consciousness then, but I was really questioning what was right and what was wrong. I was living with Walter, Tom [Capone], and Drew [Thomas] on Stanton Street, and pretty much every single one of my friends wasn’t straightedge anymore. It was just like it never happened, and in the back of my mind, I was really wondering if there really was a right or wrong. Like, did I really believe in straightedge, or was I just clinging onto the past? And was I just afraid to take another step forward because I’m afraid of what people will think of me?

So one day, me and Walter got these tickets to see Morrissey. Walter was like, “OK, Porcell, let’s go to the Shake Shack and get some pot and we’ll go to the Morrissey show.” I loved Morrissey so much, and I was so excited to go to the show that I just got caught up in it and I was like, “OK, man! Let's do it!” [laughs]. So sure enough, we went to the Shake Shack. It was pretty funny. It was just like high school, we went to the bathroom and smoked pot in the stalls. It was so juvenile. Anyway, I hadn’t smoked pot in so long I didn’t think that one joint was going to do anything for me. I was like, “Are you sure this is enough? I mean, if we're gonna break the edge, we better get stoned!” So, yeah, we smoked it and we were just baked. I remember just watching Morrissey and freaking out. We had fourth-row center seats, and it was so strange. Everything was moving slowly, and… How can I describe it? I don't know. I remember that I kind of enjoyed the concert and that when we walked out, I was getting super-duper paranoid. I was like, “Dude, there’s so many people, man. We’re like rats in a cage, Walter! We’re like a bunch of ants!” He was just laughing at me. And then, well, I don’t know if I want to get into that…

The squirrels?

PORCELL: Yeah.

I actually think that's an important part of the story.

PORCELL: OK. So me and Walter were walking home, and I was still completely stoned. I was getting all these weird revelations. I was like, “Walter, time is so relative! Don't you get it? Look at how fast that squirrel is moving! He lives his whole lifetime in five years! Just think about a fly that buzzes around and dies in a day! I'm freaking out, man! Time is nothing!” He was just laughing at me the whole time. So anyway, I woke up the next day really sad. I was really depressed because in a real way, deep down, even though I was questioning what was right and wrong, I knew. And I knew that in my heart, smoking pot and getting drunk, it was just wrong. I wasn’t into it. I mean, I felt like we had something so good and we were examples to so many kids. It was crazy to throw it all away for something so stupid. It was such a cheap thing. I was always into self-discipline, and even though I wasn’t a Krishna, I was into self-control—even if it was sex or chasing down girls. I just felt like it was wrong. I couldn’t explain it philosophically, but afterwards I felt pretty bad. And I remember me and Walter went to go see Morrissey again, and I got caught up in the whole thing again, and that’s when I realized it was no magic thing. It was stupid.

So that whole time in New York was such an important time. I had just got back from California, and it was always my dream to go there. I worked at Revelation, a few blocks from the beach, and there were so many straightedge kids in the town and they were psyched. I had the “street cred” or whatever you wanna call it. I had friends, tons of money, fans, a cool motorcycle, a cool job—I had such a big false ego. I thought I was so cool, but I was such a fool. And even though I was living out my dream, I couldn’t figure out why I wasn’t satisfied. I felt lonely. And I guess the stuff that I’d heard over the years just from whatever little association I had with the Krishnas about how materialism doesn’t satisfy a person and how no matter what material situation a person was in, there will always be distress, it was all coming back. I remember sitting in California and just thinking about how much this sucked. And I picked up and moved back to New York. It might sound corny, knowing what you know now, but I really knew that when I got back to New York I was going to go on some sort of spiritual search. I’d already cornered the market on all these different material situations, and I just figured that since I had no spiritual life, then that’s what I must have been missing. And I knew that I didn’t want to do drugs and get into the whole party thing because I tried it again and I knew that it sucked.

I got into so many things. I was into New Age, crystals, Buddhism, Taoism. I had all these books on Taoism, but it was so confusing. It was like, “Walk, but don't walk. Run, but don't run.” I was like, “This is it! If I could just learn how to think, but don’t think! It’s so spiritual!” [laughs] I don’t know. I was pretty into health food—no sugar, no white flour, no dairy. I’d exercise like crazy. I was really into purifying the body, and I always knew that I wanted to try to purify my consciousness, too. It’s weird because I’ve always been an idealistic person, and I always knew that stealing was wrong and that taking advantage of people was wrong, but there I was, working at this health-food store, just stealing all this stuff. I’d have bags of groceries. So all these things in life that I knew were wrong, I couldn’t do it. It was such a frustrating thing for me. I started reading Prabhupada’s books, and it was really attractive. It was a spiritual life that you could do in a practical way. It wasn’t some kind of paradoxical thing that you couldn’t figure out. Then, Steve [Reddy] from Equal Vision moved back to New York from the Krishna farm in Pennsylvania and asked me if he could stay at my apartment. So from there, he would bring me to the temple and we’d read together. We’d even go to the gym together, and he taught me all the prayers to offer my food while we bench-pressed [laughs]. And I started chanting. I could see how the more I practiced spiritual life, the more I was able to get rid of all these bad habits that I could never seem to get rid of on my own.

And how about making a commitment? I mean, I remember when you were coming to the temple with Steve and he’d be like, “Porcell’s so into it.” I didn’t believe it until the day you told me you were moving to the farm.

PORCELL: At that point in my life, I really didn’t care about what people thought. I didn’t care if people thought I was a jerk or brainwashed, whatever. The reason I didn’t tell anybody wasn’t so much because I cared about what people thought of me, but more because I didn’t want the hassle of them trying to talk me out of it. I really felt like there was some truth in Krishna consciousness, and I just wanted to dive into it. I wanted to live the lifestyle, and the situation was presented to me. I knew Walter would try to talk me out of it. Sammy, too. And even though we didn’t hang out that much at that point, I really have a deep sentimental attachment with those guys. So I didn’t tell anyone. Not even my landlord. I just sold my whole straightedge t-shirt collection to some French kid.

Well that's story number two: the day you went into Reconstruction Records and sold your legendary record collection for one thousand dollars.

PORCELL: And I told them it was to buy a new motorcycle because I was afraid that if Dave Stein knew I was going to join the Krishnas, he would have never bought them. He knew that for me to sell my record collection, it must have been a big thing. I mean, we grew up in the same scene; he knew that my record collection was my pride and joy. Of course he wanted to buy them, but he kept pressuring me to tell him why. That was the first thing I came up with.

Honestly, have you ever regretted that? I mean, I didn’t have a third of the record collection you did, and I do sometimes kick myself for selling mine.

PORCELL: At times, I do. You could look at it and say it was a false renunciation thing, because you can be into Krishna consciousness and still have a record collection. You don’t have to sell everything you own and shave your head and be a monk. But I think that at the time, for me, I was so attached to music that I just had to break all my attachments. I’m a lot more balanced now, and I’m pretty strong in my spiritual life. I’m able to do what I used to do now in a Krishna conscious way. But I think I needed to do that when I did, and I don't really have any regrets.

It’s hard to believe that it's been three years since then.

PORCELL: It’s kinda strange, huh?

Are you really happy now?

PORCELL: You wanna know something? I’ve definitely had the best three years of my life, without a doubt. I’ve learned so much and I’ve done so much, I think that it’s actually incredible that it’s only been three years. I feel like a completely different person, and that’s kind of cool. I feel like I can finally live up to every ideal that I ever had. I always wanted to use music in a way that was really going to change people. I mean, even in Youth Of Today. It was so depressing to me to know that we went out and pretty much preached straightedge and vegetarianism to all these kids and now, three years later, who's straightedge? Literally 97 percent of the kids that were straightedge then aren’t straightedge anymore. It actually made me sad. People’s hearts weren’t changing. They’d go to college or get a little older and they’d do what all their friends were doing. But now, with Shelter, we can give a whole philosophy on why to be straightedge or why to be vegetarian. And now, I feel like not only are we giving people the cause, but we’re also giving people the process. We’re giving people the end and the means to the end. It’s not just a slogan anymore.

Vraja Kishor [from 108] said to me four years ago how he used to watch Ray scream, “Make a change!” but you’d never really say how.

PORCELL: Exactly. That's it. And that’s why people would laugh at it, because it was a bunch of kids screaming slogans and not really digging into why. So now I feel like I know how to make a change, and I want to make it.

OK. One last question [smirking]. Now that it's off your chest…

PORCELL: [Laughs] You kill me, Norm.

How do you feel about it? I mean, I think that people knew, but now they know.

PORCELL: Yeah, they know. But you know something? My track record ain’t that bad. That’s not so bad for ten years of full-on straightedge.

Do you feel like anyone will be let down?

PORCELL: Well, what can I do? It was a learning experience, and everyone comes across stumbling blocks in their life. The moral to the story is that I went on and that I stuck with what I really felt was right. If people just hype that part of the story without realizing why I told it or why I came clean or what the real point of it was, then that's their thing. I know why I’ve said what I said.

So it’s important not only to have the story, but the conclusion.

PORCELL: Definitely. And I'm sure a few kids will get a kick out of finding out when the singer of Project X got stoned.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

this interview is so interesting because he immediately mentions the trauma that happened to him - deep rejection and alienation from a parental figure at a vulnerable age - and then spends the rest of the interview talking about the coping mechanisms he sought out to alleviate that pain, but he seems not to connect that inner void with the early trauma? I hope he's doing better now. thanks for resurfacing this interview!

Proving that time is indeed nothing, I vividly remember reading this interview back then right down to the record store where I got my copy, to the records I got along with it and the shows I went to and played that week into weekend,... and it's a little surreal reading this again today and having the same giggle factor thinking about Richie Birkenhead walking in during that scenario (mostly because I imagine his reaction being the same as watching Into Another live). Which reminds me,...

If anyone ever animated The Chronicles of Porcell per this interview, like those 911 tape animations with the animal characters or maybe Charlie Murphy's True Hollywood Stories, that would be pure comedic gold.

Thank you for making 1995 feel like it was this morning again.