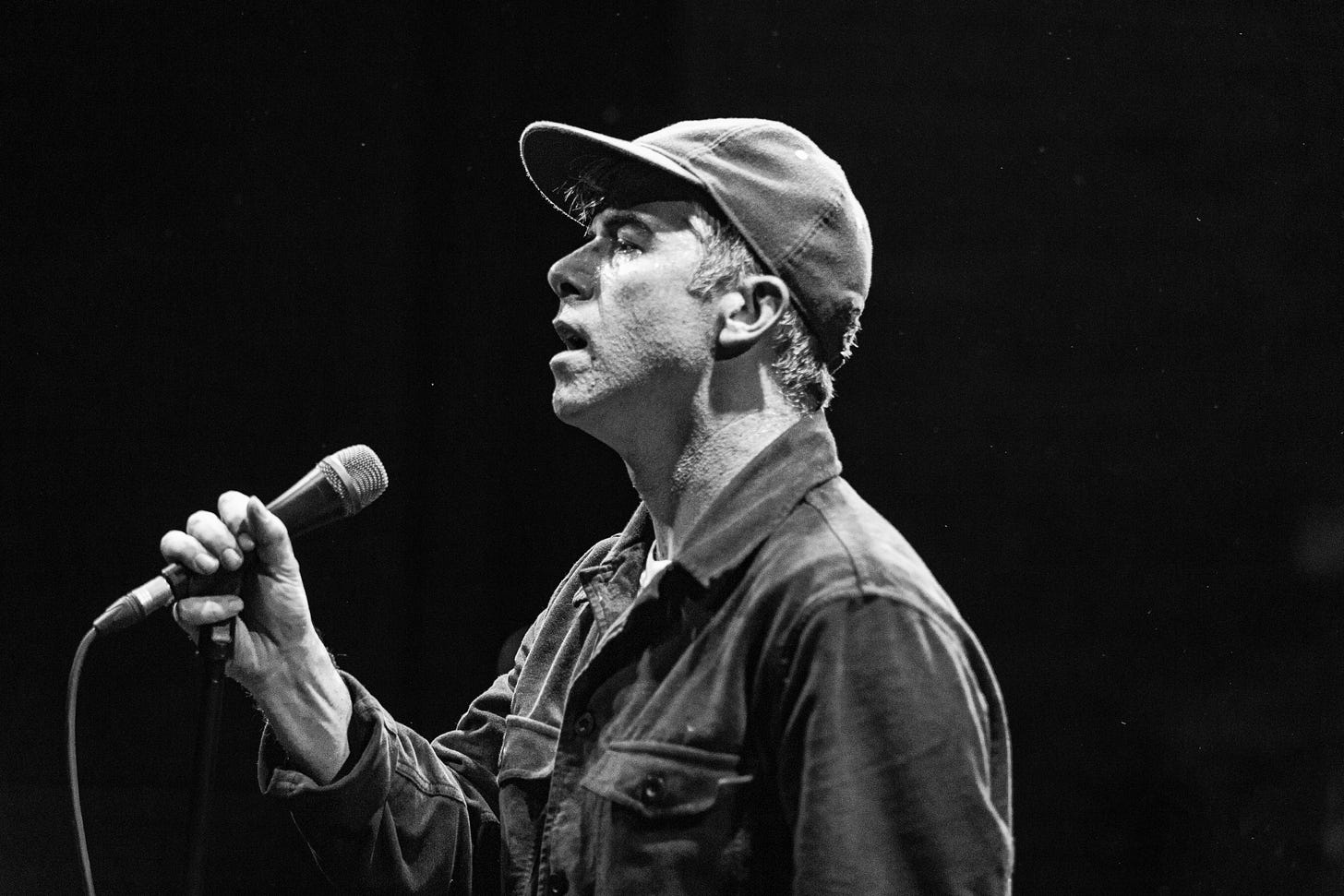

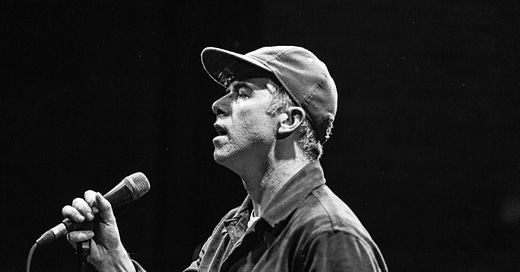

In Conversation: Pat Flynn of Fiddlehead

Over five years and three albums, Fiddlehead have traversed through loss like no other band before them. Pat Flynn wants you to know that all is full of love.

It used to be that if you were a hardcore kid who wanted to process the death of a loved one through music, you probably needed to find another genre; for me, when I lost my best friend in 1990, that meant listening to songs like “Untitled” by The Cure or “I Know It’s Over” by The Smiths on repeat. Hardcore punk didn’t feel like a vehicle that could carry grief at that time, and whatever attempts we had back then only ever scratched the surface.

But hardcore has evolved so much in the last 30 years, both stylistically and thematically, that we have finally arrived at a place where it can convey a more complex range of sentiment, beyond mere anger or disappointment or political strife. Fiddlehead have certainly tested those boundaries with unprecedented persistence, and on Death is Nothing To Us—their third album, out tomorrow—singer and lyricist Pat Flynn walks us through even more nuanced layers of the heartbreak stemming from the 2010 passing of his father, LTC Richard Flynn.

It was inevitable that I’d want to sit down with Pat to really get between those layers. But what I discovered in the process is that the only difference between “grief songs” and “love songs” is the way we choose to perceive them.

First things first. The best line on the new record by far to me is: “Deeply depressed kids seeking art to mean more than a gathering of friends.”

PAT: Oh man, I'm glad that one stuck out. [laughs]

I mean, obviously, if you’re going to call a song “True Hardcore” that’s the first place I’m going [laughs]. But I guess reading that made me wonder if you carried some kind of depression into your experience with hardcore, and maybe what it was about the community that made you feel like it was a safe place to park.

PAT: Retrospective psychology is always dangerous for me, but there are certain moments that stand out to me—like the first show I went to. It was the summer of 1999. That was my first real hardcore show. I was 14 years old, and the closest thing to hardcore that I had was the Revelation In-Flight Program comp. I don’t know how that wound up in my little pile of mostly Epitaph Records stuff, but it was there.

I showed up to the show kind of punked out, which I thought was the code. The show was Grey Area, this band All Chrome, this band Before I Break, and the opening band was The Products, who changed their name to Beyond Authority. They were the main pull for me, because the local Boston street punk stuff, to me, was like the “legit” stuff after Epitaph. Anyway, there was this guy in the local New Bedford hardcore scene named Eric Yu—I think he was in Before I Break at this time—and he walks right in wearing a peacoat, and sees this other man who’s wearing a sweater, and they just totally embrace each other. Like, I’m talking full-on hugging each other, rocking for thirty seconds like they were brothers separated at birth. So I go to this show expecting to be punk, and it’s like, here are these two men openly embracing each other, celebrating something. It was like, there’s just this bond of friendship here, and all of the stereotypical ideas of masculinity and punk just went out the doorway.

And then the show progressed and All Chrome played. I didn't know who the hell All Chrome was, but they were local heroes and every single person—every single person in this room, probably like two or three hundred people—knew all the words, even though it wasn’t on Fat Wreck Chords or Epitaph. And I was like, “Oh, this is communal. This is a local thing. People care about this like it’s a big deal.” It just felt like a door had opened for me, and it felt like I could be a part of this. It left an imprint on me.

What experiences in your life brought you to that door?

PAT: I think being an Army brat and being shoved around a lot. I moved to Columbia, Maryland, when I was five years old. It was an Army brat neighborhood, so there'd be a lot of families moving in and out, and I had apparently moved into the house of “the beloved child of the neighborhood on Red Apple Lane.” And so, you know, the early childhood or early adolescent reflex among the kids in the neighborhood was that I [was responsible for moving] this kid out. My brother and sister were a little older than me, they socialized a bit better. But I remember these kids just wildly teasing me. I was desperate for friends. I was desperate to have other kids to play with. It’s a distant memory, but I just remember trying to hang out with kids and being told, “Get the fuck away from me.” I couldn't connect.

But there was this one kid, Gregory, who was a year older than me. And he left a massive mark on my life, just in terms of the codes of friendship and whatnot. He was friends with all of them, and for some weird reason, he just thought, Hey, this isn't OK. I'm gonna be friends with him. He has no one to play with, so I'm going to play with him. So me and Gregory would go off on these adventures, and we’d swear in the woods, and we’d just be kids for these two years.

I’ll never forget though. It’s branded in my mind. My father retired from the Army to go back to Massachusetts. And I had this true bond with Gregory. So we got to have one last sleepover. The whole house was empty—and an empty house is a very stark image if you've lived in it, especially when you're a kid. The next morning my father is in the blue Volvo, it's totally packed, and he picks me up, and Gregory is waving goodbye. And then my father's car starts driving. Gregory runs along with the car and is waving! Just really strong visuals like, I'm leaving this friend. And then we were just planted into this town in Massachusetts that truly looked like it had not updated itself since the 1950s. I’d gone from a very modern looking public school to a Catholic school. I just felt totally out of time, and I had lost this friend Gregory, and I just wasn't making any friends. It’s nothing too traumatic, but I just think that kind of moving around, you know, kind of messed me up a little bit.

I mean, what you’re talking about is basically a serial displacement, which can definitely fuck you up [laughs].

PAT: My brother and sister were moving around a lot longer. I don’t want to talk too much about their own lives, but I got a front seat view as to how more and more displacement really negatively affected them, in my opinion. It was a really tough journey for the two of them. And I saw things really start to unravel.

I think the reason why I asked whether you would have described yourself as depressed back then is because a lot has been made about the Fiddlehead grief narrative—the “grief motif,” right?—and I’m trying to parse the difference here, because there’s a difference between depression and grief. Even on the new record I noticed that you managed to get the word “depress” into the lyrics of the first six songs [laughs]. So would you have described yourself in that way back then?

PAT: Oh, totally. I remember I had this huge blowout with my father in the first month of high school. It wasn’t physically violent, but he and I had a terrible argument and I ran away that night. I mean, if you want to talk about memorable feelings… I was just losing it. I was thrown into this high school and I was clearly in this terrible transitioning state. I went from this small class of fifteen kids and then suddenly there were 500 classmates of mine. I was just this animal rattling around. And for some reason one night, I think I wanted to go ride my bike the next day, and my dad said, “No, we have plans,” and I just flipped and I punched the wall. You can still see the mark in my mom and dad’s room to this day.

So I just ran out the door because I knew. I was like, “Holy shit, I just put a hole in the wall.” I ran through town and I was thinking, “My father is going to be getting in his car to chase me.” It was like I was running away from the warden or something like that. I ran to where I thought my girlfriend was at the time—it was a failing girlfriend-type situation [laughs]—and her friend’s house, where I thought she was staying, was near a graveyard. So I remember looking to take refuge in this graveyard. I’ve actually never talked about this! I’m OK with talking about it, but I’m just remembering it… Anyway, I remember the loneliness of sitting in that graveyard at 14 years old, evading my father, on a dead quiet night, just sitting there in the amber lighting of the streetlight. And I just thought, I have so much left of life. I don’t even know why I’m doing what I’m doing. I can’t explain these emotions, they’re just coming out of me, and I don’t like that they’re controlling my physical movements.

I think it's just a bit of my disposition. I definitely tried to really zero in on that as explicitly as possible with this record, so when we were writing—like when I was doing the vocals and my bandmates were checking out the lyrics—they were like, "Hey… Everything all right, Pat?" [laughs] Alex Henery was like, “I'm not worried, but this is some pretty depressing content.” And I guess it turns out I use the word “depression” in the first six songs!

It's funny because I can't even think of that many songs that use it. Like, it's not like a very tuneful word [laughs]. I mean, there’s “Drown” by Burn—”this de-press-ion!”

PAT: Oh yeah, I mean, when I first heard that song I was just taken by it. I mean, that 7-inch is just great.

That song, lyrically, is one of the greatest hardcore songs of all time in my opinion. Partially because I can't think of another hardcore song before that that talked about depression in such a real way.

PAT: You know what does really talk about it—and this to me, while writing this record, it's been a little bit of homecoming to where I was when I first found punk music, because my brother loved Black Flag—but the song “Depression.” Right on the nose! I was attracted to the lines of “depression’s got a hold of me,” but it doesn't just stop there. He’s got to break free. There was something about that willingness to endure—to quote William Faulkner, the human condition’s ability to endure and see it through. So while I've been attracted to the dark, there is this kind of hopefulness that I can't seem to kind of get away from. I look at all the records that I've written and while they’re actually all prone to sadness, there is ultimately a positive tension to it, and that is a reflection of who I am and how I function.

This band wasn’t intended to be this portrait of Pat grieving the loss of his father. I try to write about things that are on my mind, and if someone is providing musical sounds that inspire those things in my brain, I’m going to chase it. Any cognitive behavioral therapist would say this is a very healthy way to deal with this kind of stuff.

Obviously, before having these conversations, I always try to read as much as I possibly can—trying to read about what you’ve said before, but also how other people have talked about the music. In your case specifically, I feel like the overarching discourse around your band is always based on grief and loss and sadness. And all of those things are there. But I remember when my dog Bosie passed, seeing this inspiration post or something on Instagram that was like, “Grief is just love with nowhere to go.” And I was like, fuck. That changed my life. Because I immediately felt like I understood what I was feeling; it changed how I felt about grief. And so I guess what I'm saying is that if I choose to think about grief in that way, then in a lot of ways, I have to think about your records as love songs.

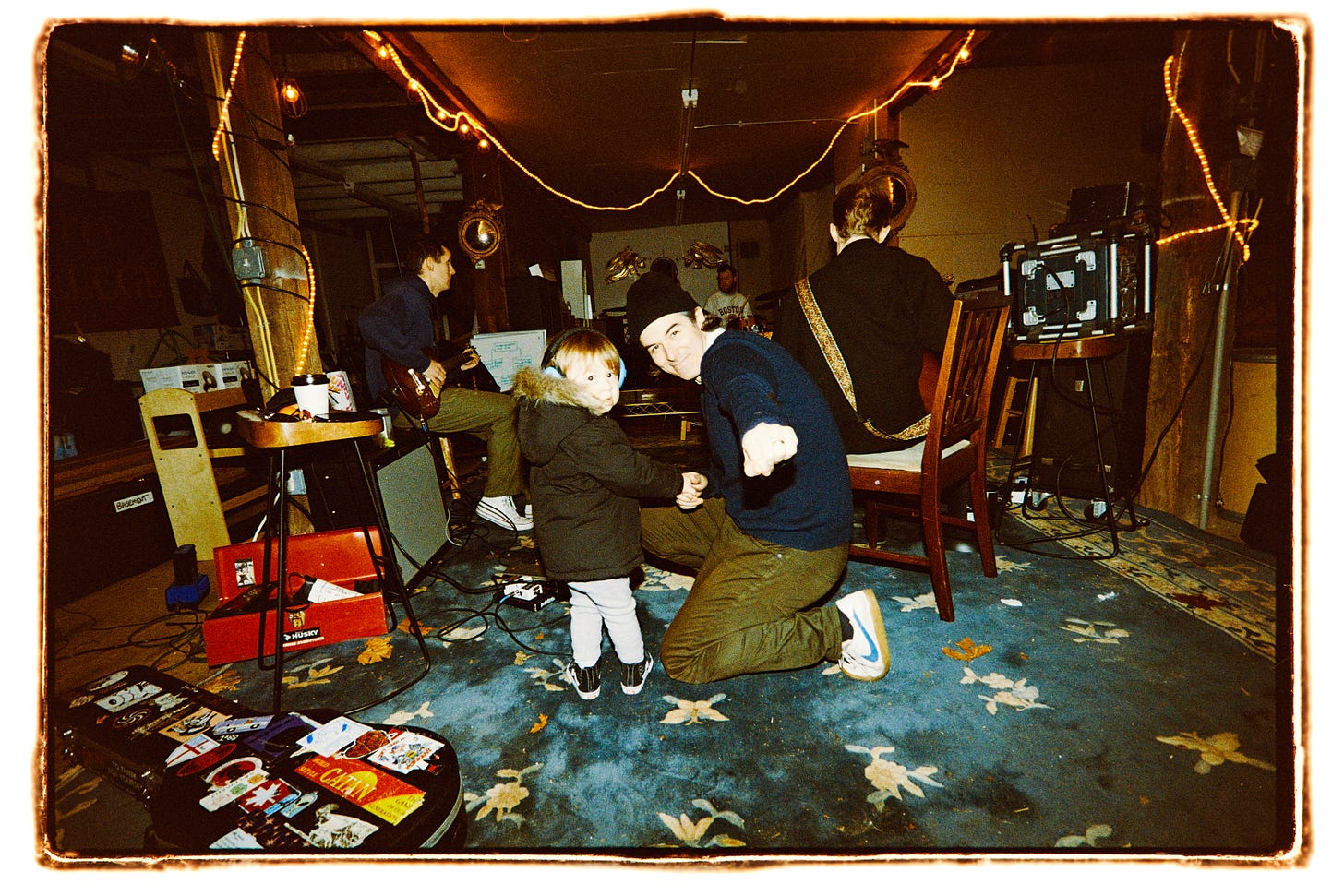

PAT: That’s it! I mean, that's the nail on the head. They are total love songs, some more explicit than others. There was something on the last record—the line, “What would you think of me now?”… I spent my days missing my father and then it became far more overwhelming when I had children. My father passed when I was already at a pretty low point in my life, in our family situation. My brother was in prison. It was big. But any type of achievement I was making, there was always this constant, “What would you think of me now?” It just became overwhelming when my son was born, and I had to write that line.

I see those first two records as, like, real communications with my father. They’re conversations. I don’t know if you’ve ever read The Road by Cormac McCarthy; it’ll just rip you up. But there’s this part where the father passes and the son is kind of left on his own, and he promises to continue to speak with his father every day in his own way. That’s just buried deep in there. I think on those first two records I was really trying to make those conversations with my father automatic, develop an automaticity. We don’t play that much, so when we do, it’s great. I’m so grateful that I can have this career as a teacher and play as a musician, because it really makes for those moments to be totally sacred. Not that I'm having this outer body experience; I've written these words intentionally for this specific moment. And it's an opportunity to communicate with my father in very explicit ways, but also where perhaps other people in the audience are doing the same thing in their own weird way. So definitely those first records were me trying to build some type of bridge to continue the love I have for my father.

Are you ever worried that writing so much about this topic could eventually desensitize you from feelings you might still need to have?

PAT: I don’t think so, no. Because, for me, there’s just an eternal longing for my father. It will never go away. I saw some random video of Billy Bob Thornton saying, ‘I've never been the same since my brother died. I will never be the same’—and I understand that. A desensitization towards death and loss, to me, speaks to an unhealthy way of dealing with it. But what I’ve really tried to do is look at death and loss as a part of the life experience and really welcome it into the daily conversation so that it’s not weird. In the first few years after my father died, I remember feeling weird talking about him in the presence of my friends, and then feeling weird about feeling weird. I really want to rip that part out of it. That’s why I’m happy to speak kind of openly about it. I think you get desensitized when it’s internalized, when you’re only having conversations with yourself and you continuously feel weird.

The risk is definitely there, but you’ve got to walk the line of a healthier approach to it. I think avoiding the romance of grief is important, because it’s very easy and emotionally comfortable to sink into this state of profound loss. It's soothing to feel broken and sad in the extremes of it—almost to the point where, like, I’ve never really done any major drug, but there’s some neurological stuff taking place when you're going through it.

Absolutely. To be honest, I think this is actually another place where my personal experience with depression brushes up against this conversation. Because at some point, I started to understand that I was getting this almost perverse pleasure in being depressed—where I could indulge in my depression and somehow paradoxically feel better, the worse I felt [laughs]. I had to finally identify that as a problem. The indulgence is problematic.

PAT: That’s really why I wanted to really write about it so explicitly. Because that's just sort of always been there with me and I wanted to be rid of it. I'm a father, I have a career, I've had success in writing music and collaborative activities. I just thought, I should be over this. This is middle-school-Pat-Flynn, graveyard-night stuff. I'm nearing my forties now. Let's be done with it. And so it was enraging that I couldn't just turn it off.

I think my father’s generation, they just didn’t let in any element of depression, and so the way in which it came out was through a lot of explosive rage and anger. That's not healthy. So it’s about finding the door to let it in. At the same time, if you let it in too much, you can really sink into the woe-is-me [mindset]—and then suddenly life is really only about you. And the way you might handle some type of conflict with another human being lacks total perspective, and the arguments turn into fights without resolutions.

There are giant signs that you have indulged too much. At one point, I started to indulge too much and I lost the love of my life. About a year and a half after my father passed, I lost my wife. She was like, “You’re gone. You’ve been taken by this.” And in this life, you can have communal support, but you get out of these holes, ultimately, when you make the decision to get out—on your own. So she left. And then I went into so much of a demoralized state that I started Fiddlehead [laughs].

As a side note, the reason why it’s called Fiddlehead has nothing to do with the vegetable. It was really because my wife introduced me to the vegetable, and there was something about the way that she said it—the way it sounded—that I just loved it instantaneously. I just like the way that she said this word. So when I was starting this band, I wanted to face that profound loss of losing my father, my brother was in prison, and now the love of my life is gone. While some people might find the name quite pleasant, for me at the time, it was a source of profound turmoil, because it was not just a name. I don’t see the name and see the letters. I see her voice. And I didn’t have that anymore.

Do you ever just want to talk about something else?

PAT: It’s funny. The name of the record is Death is Nothing To Us, and when I presented that, I tried to be mindful about it. It was never like, “I want to be a new band,” or, “I want to park this as the end,” or, “This is the end of the trilogy! We are no longer going to be talking about that.” I’m going to talk about whatever is eating my brain, because I think that makes the live performance really powerful and what helps create greater connective tissues with people out there. But when I was finalizing a lot of the lyrics, I very fortuitously went to my history department book swap. I got a book by this historian, Stephen Greenblatt, and in the preface he’s talking about how—and this is a little complicated—in the fifteenth century there was a papal secretary, Poggio Bracciolini or something like that, who uncovered this ancient poem from a Roman philosopher by the name of Lucretius called “On the Nature of Things,” and in that poem is the line: “Death is nothing to us.”

[The Church] had been using death and eternal damnation to keep people in line, just using death to sort of control you. And it was powerful. But then hundreds and hundreds of years later, this random secretary finds it, and Greenblatt—a 21st century historian—argues that this helps set in motion the return to life of the Renaissance, from what was a deeply stuck-in-the-mire medieval Middle Ages. And, you know, from that you get some beautiful ideas. You get a lot of gross stuff, too, out of Europe. But you get a pretty powerful reawakening coming to life that brings us into a little bit of modernity. It’s an argument. I don’t know if I was buying it, but what I was most struck by was that the historian in the prologue was saying, “I found this story two years after my father had passed and my mother was grief-stricken. She was wildly lost in the throes of grief and death.” And that just completely resonated with me and seeing my mother struggle with losing her husband. So there I was, like, I got this book randomly at a book swap and I'm writing these lyrics and it was on the nose of where I've been trying to get since my father passed—really struggling to not be under the thumb of something, I guess you could say.

You’re a 108 guy [laughs]. Your interview with Rob [Fish] was very powerful to me. 108 was huge on my life. They had this lyric: “Abandon the deathlife and reignite the light.” Something about this concept of “the deathlife” really struck me. This idea of living through this kind of woeful dance, or obsession with death. I really wanted to break any idea that that’s what this band is about—a romanticizing of grief and death. Personally, I wanted to explicitly make a stance in my life that death and its power to influence life is nothing compared to the power of life. What comes first is really striving to just live life, and not just endure it, but to really experience and soak up all the things that magnify its beauty while we’re here.

When you’ve talked about your approach in Fiddlehead, you’ve said, “I wanted to historicize it. I want to memorialize it. I want to poeticize it.” So I get the memorialized part. And I get the poeticized part. But the historicized part always made me feel like—is that what you’re really doing?

PAT: It’s a good question. I write very personally and it’s very difficult to understand the whole person. So I have these records and they’re kind of portraits of where I am at that point in my life. But perhaps the better thought is that this historicizing of who I am is, to me, more like: what will my children have of me? They’ll understand that history is more than a single source, but they’ll have these documents of me singing—tangible evidence of who I was at this point in my life. Like, I’m really happy that I wrote the way I did when my son was born, and likewise with my daughter. I was left with so very little of who my father was when I was born. It’s not there. So I see it as providing a piece of history, I guess you could say. It’s not an end-all, be-all of who I am—I’m far more complex than that—but if I step back and I look at everything I’ve put out there as a lyricist in this weird world where I don’t even consider myself a musician, it’s still a part of who I am. I’ve been very lucky to have this platform.

Do you think you’re ready or willing to expand the range of emotion if there’s another Fiddlehead album?

PAT: I mean, totally. I’m getting older, and I’m happy to encounter a lot of the mundane, banal elements of life. Having my children is very paradoxical because it’s simultaneously the most exciting and emotionally raucous experience I’ve ever had in my life and also some of the most boring times of my life. It honestly reminds me of how my father described being in the Vietnam War. He didn’t speak that much about it, but he said that it was just rapid, wildly horrific moments—like, single split-second moments of fear and horror—coupled with centuries of boredom. And all the while that boredom horribly intensifies by the threat of another single split-second moment. Not that having children is like going to war [laughs]! It’s really the best thing; it’s the antithesis of war. Because there will be these jolting, shocking moments of profound joy.

I'm leaving for two weeks tomorrow, going to Japan, and I told my son I was gonna be gone and he was just dealing with it, so he went out on the doorstep. He’s not supposed to leave the house without telling us; he’s only four. But he left and he knew he wasn’t supposed to do that. It was a little act of defiance, just his little emotions trying to deal with something that he really doesn’t like. So in his tiny act of rebellion, he opened the door, but he didn’t leave the house. He just sat on the front step. And even now, I just sort of think about when I was wrestling with my emotions as a teenager and I slammed that wall and I left the house, and I think about the cycle and how it’s not repeating. I could have taken the authoritarian parent route—like, “You should not leave the house!”—but instead, it was this wonderful moment of like, “Hey. I see you struggling with something that’s really tough and it’s got you down, and I’m leaving for two weeks, so let’s sit down on the front step together and just be at peace.” It was really nice. They’re hard moments that are, to me, the height of life. That’s the tiny little jolt that I live for, and it makes the boredom completely worth it.

I say this because much of my life is pretty boring. I mean, I’ll spare you the details, but I still get the bouts. I want to get out of this thing that’s on me—of being a depressive guy. I very much read publicly as a sunny disposition, happy guy, and it’s not like it’s a wild disaster when I’m really feeling it, but [the depression] is still totally there. But who wants to hear a record about being bored, and then also the wonderful joys of being a father?

It depends on how you do it? [laughs]

PAT: I will write that if it's going to come out… The sound always has to have emotion for me. The experience writing with the guys in Fiddlehead is unbelievable. We all come to the table with what we have and it's super democratic. We all just want to build each other up and it's very magical. I'm very skeptical on how long that can last.

There are other topics in my life that I would really want to write about, but the sound has to come my way. And I don’t know if it’s in the wheelhouse of the fine young men of Fiddlehead. I also don’t think it’s something sonically that a lot of people would enjoy. I mean, it’s not powerviolence; I can't describe it. “Curse of Instinct” is like the closest thing that would capture these moments in my brain. But Fiddlehead… if we wanted to write a record about me exploring my infinite love for my wife, I’m gonna write it. I am constantly in awe of her. So if the sound is there, and the riff comes my way, and it meets that, that is always on the table. There just has to be a matching between the emotion and the sound. I don’t know of any other way to write music.

Truly, this is the most precious art form out there. And just to circle back to that line in “True Hardcore,” there's nothing greater. I’ve gone to all the national museums. I've seen the Mona Lisa. I’ve seen Van Gogh. You name it. Nothing compares.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

Sometimes you read something, a book, a play or in this case an interview, at the right time and the right point in your life. That was today, thank you.

"Striving to live life, not just endure it" - a line I'm going to be thinking a lot about today.