In Conversation: Sammy Siegler of Rival Schools, Youth of Today, and Judge

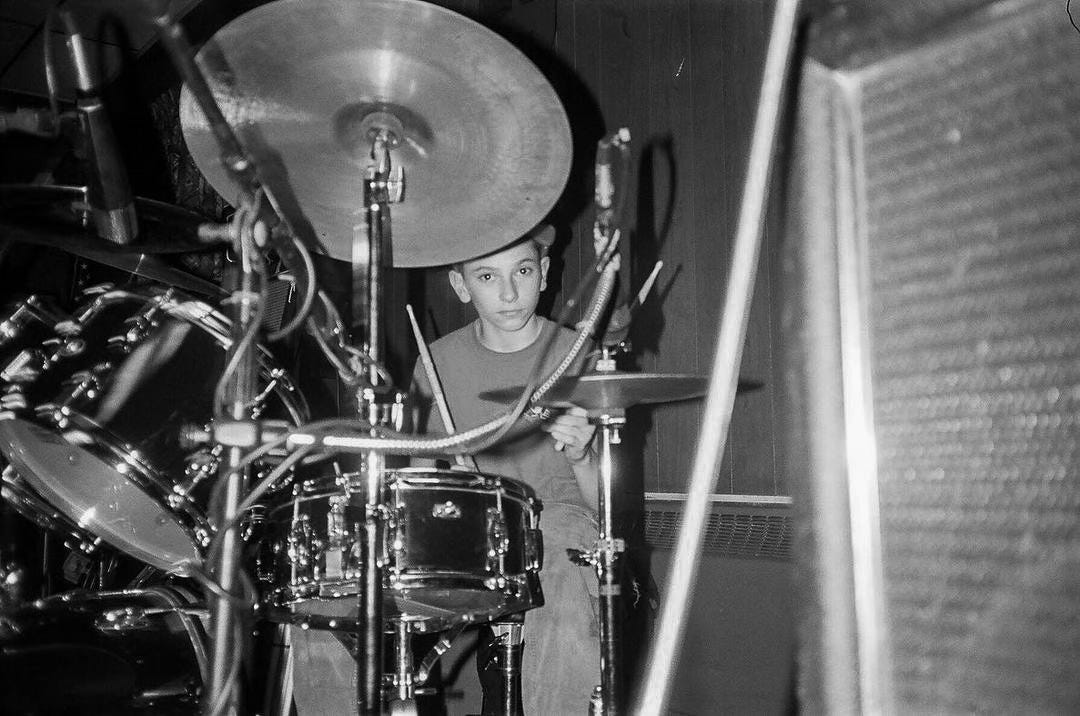

He's been the drummer for your favorite bands since he was eleven years old, but he never allowed growing up in public to narrowly define him. At 51, Sammy Siegler remains open to every possibility.

If you were in California this past April, you may have noticed something entirely unique and unprecedented happen. In one weekend, over three different shows, five separate bands all played their respective sets with the same drummer. On April 12, we saw 7 Seconds and Judge. On April 13, it was Youth of Today and Side By Side. And on April 14, Shelter had its turn. The connective tissue for all of them was Sammy Siegler. Even more amazingly, these five bands represent only a fraction of the music that Sam has played a part in over the last 39 years. Throw in Rival Schools, CIV, Gorilla Biscuits, Glassjaw, and Project X and you still might be only halfway there.

As Run For Cover prepares to reissue new versions of two classic Rival Schools albums next month, it felt like a good time to catch up with Sam for a conversation that explores both how an eleven-year-old kid in a leather jacket went on to become straight-edge hardcore’s most legendary drummer and how that kid—now the adult father of a fourteen-year-old daughter—remains, quite possibly, more creative and active than ever. “I think this is the thread,” he tells me. “I’m not like, ‘I don’t do that’ or ‘I don’t do this’ or ‘That’s not hardcore.’ I want to be open to things.”

One thing I’ve noticed is that, historically, you are very specific about the way you talk about your childhood. You never talk about growing up in New York City; you talk about growing up on West 15th Street. Not even a neighborhood, but a street [laughs]. That is a very New York way to talk about where you’re from. We identify certain streets in a way that’s legible to us. But for the majority of people who have no idea what that means, how would you describe that street when you were growing up? Because if we’re talking about West 15th Street in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, we’re talking about a very different West 15th Street from what it is today.

SAM: That’s an interesting point. It’s true, though. It’s not even like saying, “I grew up in Queens,” or “I grew up in Brooklyn,” because West 15th Street is such a specific little pocket. It’s not really Chelsea, it’s not really [Greenwich] Village. But I always referred to it as the Village because my dad also had a business and a building on West 11th Street.

My parents bought this loft in 1974 that was a floor-through in a building that used to be a factory. This guy who had the top floor started it, and the idea was that it was only meant to be for artists. My mother was a copywriter, so I guess that sort of deemed her as “an artist,” and she was able to get in. But it was totally raw and fucked up. The elevator was one of those manual ones that you had to operate yourself. So there was this whole system where, if you came in and the elevator was on the ground floor, you could take it up to your floor. But then if someone else needed the elevator, they would ring a bell, and then you’d have to go to the seventh floor to pick them up and bring them down, and they’d drop you off on the way down. After that, the elevator was on them. It was like a game of tag.

Specifically, 42 West 15th Street. There was a giant parking lot next door. I remember that. I knew the guy that ran the parking lot. His name was Charlie. My mom sometimes borrowed cash from him when she needed money because she didn’t get paid until Fridays. There was this whole parking lot relationship. It’s funny. I remember when I was twelve years old and I was playing in Side by Side, for some reason I was the guy that was able to hold the money from the shows—like 60 bucks or whatever we had. And I would go get singles from Charlie because I thought it was cool to have a wad of money [laughs].

There’s another story that really ties me to 15th Street. When I was nine years old, Bernhard Goetz lived right across the street from me. One day, after he got into trouble for shooting those kids in the subway, someone rang my buzzer and was like, “Hey, I’m from the New York Post. Do you mind if I take some photos from out of your window? I’ll pay you if I can take pictures of Bernhard Goetz.” So I was like, sure. I needed a summer job; I needed money. And sure enough this guy paid me like a hundred bucks or something to hang out in my room and take pictures of Bernhard Goetz. My mom came home and she was like, “Sam, who’s that in your room?!” [laughs]. But a couple of nights later, the sun goes down, and I see this little red laser scope coming through my window and onto the wall. And then my sister was in her room and she saw it, too. We came running out of our rooms like, “Oh my God!” We really thought it was Bernhard Goetz. We thought he was pissed about us letting a photographer take pictures into his place. A lot of shit happened.

Another important part of your story is your family’s history with music, which I’m not sure I fully grasped until I looked up your father’s name on Discogs and he showed up on the Beastie Boys’ Hello Nasty. Have you seen this credit? It literally says Richard “Sammy’s Dad” Siegler. [laughs].

SAM: He was so pissed at me. He was like, “What is this shit?” [laughs]

That song, “I Don’t Know,” is actually the third most streamed song on Hello Nasty, after “Intergalactic” and “Body Movin.’” Which is kind of a big deal.

SAM: It’s a great song! It was different for them. I don’t know if you know the story of how that went down, but basically, growing up downtown, I met Ricky Powell. I kind of loosely knew him. He invited me by this basketball game at P.S. 41, and I’m not a great basketball player or anything, but I was at a point in my life where I was just psyched to do it. Sure enough, I get looped in and it’s this Beastie Boys private basketball game that happens at P.S. 41. So I just started playing. We played on Tuesdays, and we played on Saturdays, and then we added Thursdays, and I ended up doing it for like seven years. I would see these dudes more than I would see a lot of people. So it was Adam Horowitz and Adam Yauch, but it was also a lot of other kids that grew up in the Village. We had this common thread of the Village.

I had a cool relationship with Adam Yauch, specifically. They were really nice and generous. They’d invite us to the studio to listen to mixes and whatnot. At any rate, one day he was like, “Do you know any Brazilian drummers?” And I was like, “Sure, there’s a guy named Duduka, who is the session dude.” My dad knew him, so I could get his contact. But then I was like, “What do you really need?” And he said, “I just need a bossa nova beat.” And my dad could do that. He grew up playing jazz and really got into Brazilian music. He can definitely play bossa nova. So I connected him and they invited us down to the studio on Mott Street to record.

My dad is kind of this Larry David character, you know? So he walks into the studio like, “So, eh, where are these Beastie Boys?!” And they’re all right there [laughs]. But yeah, my dad ended up playing on it, and they did wind up hooking up with Duduka, who played on some stuff. We weren’t really sure what they were going to use, if anything. And then the record came out and it said: “Richard ‘Sammy’s Dad’ Siegler” on it and my dad gave me some shit for that. But he got a kick out of the whole thing. He came up in New York and Long Island just gigging, playing weddings, playing in the Catskill Mountains, playing bar mitzvahs, playing jazz and some big band stuff. So this was a first-time thing for him. It was really special.

You also grew up with [Judge bassist and Trust Records owner] Matt Pincus, right? Like, you were actually kids together.

SAM: Yeah. I went to the Village Community School and then I went to Friends Seminary, which was a Quaker school on East 16th Street. That was for fifth, sixth, and seventh grade. On the first day of orientation, I was standing in this little courtyard area and there was this kid with a mohawk. I went up to him, and I go, “Hey man, are you punk rock?” And he goes, “Yeah, I’m punk rock. Are you punk rock?” And I’m like, “Yeah, I’m punk rock!” [laughs]. We just just hit it off right there. That was Matt Pincus. He was a year older than me; I think I was eleven and he was twelve. And we just got really punk rock together. It was my Sex Pistols phase, I guess. The Clash and Repo-Man and Suburbia. We were smoking cigarettes and smoking pot and doing RUSH [poppers] and Whippits and we thought we were just punk. We tried, for sure.

Matt grew up with a really wealthy family; his dad was a really smart dude. But he was rebelling hard, and ultimately he got kicked out of school. After a couple of years, I got asked to leave Friends, too. They asked like three or four of us to leave. I wasn’t bad bad. I was just a little bit of a class clown, kind of a wise-ass. Friends Seminary today is a pretty high-end school, but back then it was a little looser, and I just think they made a decision to clean house.

There seems to have been this permissive air across your childhood, but usually when kids first gravitate towards punk, there’s a greater sense that we’re rebelling against something. So if you weren’t rebelling against your permissive parents, what do you think you were working through?

SAM: It’s interesting. I was middle class. I wasn’t poor. And my parents were really cool. They were really supportive of me. They would take me to CBs because I was too young to play, and they took me to the old Ritz because I couldn’t get in. I was just attracted to the music and the culture and the energy [of punk]. That fire and that spirit. I mean, I was really young! I was like eleven years old. So when I first got into punk, I was into anarchy and, like, “fuck the government.” I didn’t really know what that meant. I would listen to T.S.O.L. and they’d be like, “President Reagan can suck it” or whatever it was, and I just thought, “Yeah, fuck President Reagan!” So initially, I think it was just camaraderie. Once I joined Side By Side—or even before that, when I joined Gorilla Biscuits in 1985 when I was 12 years old—I was just like, I am fucking into this scene. It was too exciting. There were heroes and villains, and there was violence, and there was also this positive movement that I got looped into. And then the fact that I could play music and be a part of it and play a show or make a t-shirt or make a record… I was fucking in.

Admittedly, I was kind of a nerd when I came into the scene, but you were coming in with Matt and you were smoking and getting high or whatever. How did straightedge enter the conversation?

SAM: I think the timing was right. I was only really “punking out” for a year or two. But when I was eleven, I did acid by accident. I was going out on a Friday with Matt Pincus to meet my dad and I ran into a friend in Washington Square Park who sold me a tab of acid for a dollar. He was like, “Yeah, it’s like pot, but a little stronger.” That’s what he said. So I took it, and I kept walking, and sure enough, 45 minutes later it kicks in and I am fucking tripping. I go to meet my dad, he’s yelling at me, I’m in tears. We get into the car and I’m tripping. It was just a bad scenario.

I was still kind of punk when I met the guys in Gorilla Biscuits. I was smoking pot and I had a leather jacket. But to be around them and the guys in Youth of Today at that time, to see the straight-edge thing starting to happen, I was ready for it—because I was a little freaked out by that acid experience [laughs]. But it was the music that really drove me to all of this. To get Break Down the Walls and to hold that record and listen to those songs, to be able to meet those guys and go to the shows and they were so fucking electric, to become friends with them and to have Porcell be like my big brother—that was a no-brainer, do you know what I mean? It happened naturally and it made a lot of sense for me.

I have these very vivid memories of being thirteen years old and hanging out on the Bowery and feeling this heightened self-awareness about how young I was. Everyone I knew was at least four or five years older than me, and I was aware that I was being taken under people’s wings so I always felt like I had something to prove. There was a sense of insecurity there. I’m curious about whether or not that was a part of your experience as well. How did those feelings play out for you?

SAM: It’s amazing how much shit happened in those two years. I would hang out in Washington Square Park a lot because it was easy to skateboard there, and there was this whole scene of kids hanging out. Some were older, but it was very mixed—and I liked that. As far as being young, we kind of always had a crew. Like, Rishi [Puntes], who played drums in Youth Defense League was young, and then Luke [Abbey, from Gorilla Biscuits]… I met Luke pretty early on. He was playing in this band L.A.B. when I joined Side By Side, so I was probably twelve and he was maybe thirteen. He was just teeny, you know? We had a crew of kids. It wasn’t an issue.

It only became apparent when I went on tour. In 1988, Youth of Today went on tour for two months around the U.S., and those “big brothers” that you used to hang out with, you’d see different sides of everyone on tour. After two months in a van, shit starts to go sideways. You start to see the age difference a little bit. Like, I was going through puberty and they were already there. But it wasn’t an issue where I was like, “Fuck, I wish I was older”—because it wasn’t like they were going out drinking and partying. We were all kind of doing the same thing, which kind of made it easier.

One thing I’ve noticed, and really appreciated, is that whenever you talk about joining Youth of Today, you are always very forthright about saying it was “a dream come true.” Tell me what you mean by that specifically.

SAM: I think about how my friends Chris, Matt Pincus… we would literally go to Matt’s house and put on Break Down The Walls really loud and just start moshing and pillow-fighting [laughs]. We were just fanning out. It was pure. Fast-forward to when Mike Judge left Youth of Today, and there were these tryouts. Walter [Schrefiels] and Luke were really good friends, so Walter was pulling for Luke and Porcell was pulling for me. But I tried out and I got it. I mean, holy shit.

I would see Ray [Cappo], but I didn’t really know him very well. They were all like four or five years older than me, and again, at that time, I was like twelve and teeny. They were like superheroes, man. Raybeez. Vinnie Stigma. Jimmy Gestapo. Pete Sick of it All. Gavin [van Vlack]. These were like giant humans to me. Just muscular, big dudes. So it was like, fuck, man. I’m in Youth of Today. I’m in my favorite band. It was like, “OK, we’re flying out to L.A. to play Fenders and open for 7 Seconds and Uniform Choice”—who were also one of my favorites. Just mind-blowing. Like, big leagues. Look out! [laughs]. And then we got signed to Caroline Records and I was able to buy a new drum set. It all happened very quickly. I was fourteen. That was the big leagues for me.

Actually, mentioning Caroline brings something else up for me, because at the time, bands that were signing to labels like Caroline or Profile—that was a little controversial. In the years since then, I feel like you’ve always been kind of aloof or unbothered by that kind of stuff. Like, in the interview I did with Civ, he was recounting this story of going to out to dinner with you, Charlie [Garriga], and [legendary music manager] Doc McGhee, and how we was just struggling with this plan to sign with Atlantic to the point where he left the restaurant and called his girlfriend, crying. I never really perceived that level of struggle from you.

SAM: No, it’s an interesting point. I know what you mean. Maybe it has something to do with the roles. Like, if you’re a singer like Ray Cappo or Civ or Walter—I’ve seen him go through a lot of debates with himself over what he can and can’t do—maybe it’s just this fact that if you’re a frontperson for a band, or you’re singing and writing the lyrics, or you just have to be up there, that there’s a different kind of pressure there versus being a drummer.

But some of it I learned from hardcore. I really believed in the positive outlook—through the clouds I see the light. I don’t want to dwell on that drama. I don’t dwell on whether people don’t like us on this record or if they think the song “Can’t Wait One Minute More” was a sellout. Fuck it. I love that. Even more so now, I love throwing curveballs. The more rigid the scene gets, the more of a tendency I have to say “fuck it.” There are no rules to me.

Well, then tell me this. There had to be a thought process before you agreed to play with Limp Bizkit.

SAM: No! I mean, yes and no. It’s more that life is always going to throw you a bunch of shit, and I’m always going to be up for an adventure—assuming you’re a nice person and you're a good person. I don’t want to partake in bad shit [laughs]. But life always threw things at me. Like, I remember walking down West Fourth Street once and someone was like, “Hey, we’re doing this commercial. Do you want to be in it?” That kind of thing happened a lot. Or once, my mom told me I needed to get a summer job. And then I went to see Crocodile Dundee with a friend uptown, and when I came out, this woman came up to me like, “Hey, I’m with New York Woman magazine and we’re doing an article on New York City kids. Do you want to contribute something?” That school year, coincidentally, we had an English project to write the story of your life. So I already had it done, and I gave it to her and she gave me 800 bucks. I was like, “You happy, Mom? There’s my summer job” [laughs]. If I had to get philosophical about it, it may be luck or it may be putting an energy out there or just showing up. But these things just kind of happen.

With Limp Bizkit, it helped that it happened through a friend. I was playing in Glassjaw, so I met that producer Ross Robinson. We became friends and we were hanging out a lot at that time. He works with Limp Bizkit. So he called me up like, “What do you think of the LB?” And I was like, “What the hell is the LB?” And he said, “Limp Bizkit! They’re trying to make a heavy record and their drummer can’t do it right now. What do you think?” And I said, “Sure. I’ll meet the guys and I’ll try out.” So I did. Wes [Borland] was really cool and Fred [Durst] was a little bugged out, but you know, although I hated the “Nookie” at that time, when I got looped into meeting them later, I saw that ultimately these guys are musicians. They’re artists from a different scene, and they want to make their shit, and they want to make it cool. They were nice. They respected me and treated me well. So I didn’t really struggle with it. I remember seeing a couple of comments from the Buddyhead guys that were like, “You’re on the other team now,” or something like that, and I was like, “Oh shit, do I do something bad?” [laughs] But I’m a drummer. I play drums. Like, I remember one time I played drums for Patti Smith at one show because I knew her boyfriend and they lived down the block from me on MacDougal Street. I have this weird memory of playing on a P.M. Dawn track, but I can’t really remember that one…

OK, but both of those things have cred!

SAM: Yeah, but there was also Warrior Soul! Before Limp Bizkit, that was pretty cancellable in our “cred” world. Don Fury hit me up when I was seventeen and playing in Judge, and he was like, “Hey, my friends are in this band called Warrior Soul. They got signed to Geffen Records, and they’re going on tour with Metallica, and they need a drummer!” And I was like, “Sure. I’ll meet them.” I mean, I don’t want to make it sound like I would do anything. But I’m definitely up for a conversation. I’m definitely up for at least sticking my head in there to see what’s going on. So I played in two [Warrior Soul] music videos, and they were like, “Can you wear a bandana?” and it was a little cheesy. And then they kicked me out because I wasn’t that good [laughs]. But I think this is the thread, Norm: I’m not like, “I don’t do that” or “I don’t do this” or “That’s not hardcore.” I want to be open to things.

I think I’ve always struggled with that kind of openness a little bit. I like to think that I’ve put myself out there in different ways, that I’ve had my hook in the water. But I haven’t always been open to every bite, and there are bites that I look back on now where I’m like, “Oh, that was fucking stupid.” Like, at one point [in the late ‘90s], I got a call from someone on Trent Reznor’s team who asked if I would try out for Nine Inch Nails. He was literally like, “Trent knows who you are.” But I said, “No, I don’t think I’m right for this gig.” I didn’t even just take the chance to go down and meet him and talk.

SAM: I mean, ultimately, it will play out. Like Limp Bizkit—I didn’t last. Their old drummer came back. But I would still encourage people [to try things]. Again, don’t do shit with bad people or don’t do things that suck. But if you’re just going to go back to those rules of “you can’t do this” or “you can’t do that”… I’m not a fan of that. I’m just driven to go for it. Warrior Soul? Yeah, sure, fuck it [laughs].

My dad always talks about life as if you’re cooking food: All the flames on your stovetop have to be on and everything has to be cooking. Because if not, if your love life goes out, you’re fucked. If your family life or your business life or your music life goes out, you’re fucked. So it’s really trying to play this balancing game, and that’s kind of where I try to exist. I’m going for it all.

But using that analogy, can’t you also set the house on fire?

SAM: [Laughs] Yeah, you can. It happens. But you know, I think the nature of my instrument is that I’m dependent on other motherfuckers, for better or worse. I’ve always been envious of these people who could pick up a guitar and be like, “Oh shit, I just wrote an album,” you know? But the nature of being a drummer is that I can’t really throw myself at it; it’s all dependent on getting everyone together. I have to wait for the team.

I think one of my most breakthrough realizations in the last year has been that I have creative assets. Like, I have zero in material assets, but I have creative assets—like Anti-Matter, like the music I’ve made—and it makes sense to keep those things alive as much as I can. In the last year, you’ve played shows with Rival Schools, Shelter, Judge, Side By Side, Youth of Today, and CIV. That’s like every band you’ve ever played in! [laughs] I’m wondering if you’ve ever thought about those bands as your creative assets. Where you think: This is what I have. This is what I have to generate creativity and generate income and generate love.

SAM: Yep. There’s so much yes, definitely. I mean, a lot of things have to come together in my checklist—the main one being that everyone is in good shape physically and mentally, and wants to do it, and can play. With all these bands, it’s important to me that the music is at a high level. So fortunately, right now, everyone is in good shape and can do it. They’re all good players. The music is good. And then, is there a demand? I think there is. People want to see it, and hardcore is having a great moment right now. It’s global. So there are all these opportunities that weren’t there back then. All those things have to come together. And of course, you get paid, which is a nice bonus on top of it all, and it’s part of how I make my living, but it’s not 100 percent. When I was in CIV, I was 100 percent a “professional musician,” and it was cool, but you end up thinking about the music in a different way. There are different pressures and it takes some of the fun out of it.

Right now, I’m really thankful. I love the work I do. I do marketing with Revelation and Trust Records, and I also get to play with a lot of these bands. It’s this really cool balance. But it takes a lot of work. It takes a lot of that stovetop mentality. I don’t know if it’s being a drummer or just who I am or starting at a very young age, but I’m wired and I’m 51 now. I’ve been doing it for a long time.

OK, I thought I’d end like this: I’ve been thinking about what we’ve been talking about, and I’m realizing that in order to have lived the life that I’ve lived, I’ve had to sacrifice some things—and some of those things, like security or stability, are things that don’t suck [laughs]. But, hey, no regrets. At some point, you’re making a conscious decision to move forward and sacrifice those things for the sake of what drives you. Clearly, you’ve done the same. So my question to you is this: Your daughter is around the age that you were when you really started to get into the thick of what became your life. If, at some point, you started to see her drifting into a similar path as the one you’ve chosen, how would you talk to her about it?

SAM: I mean, my daughter is fourteen and she plays bass. The other day I took her down to this place called The Smell in downtown L.A. It’s been there for a long time. It’s like an all-ages punk club. And she was like, “Dad, I want to go back to this place. I love it.” So you can see that lightbulb going off. But I think the main thing I took away from my parents, the main thing I learned, is just communication. Always talk. Always show up. Be present. I feel like, with that, we can get through almost everything. Hopefully I would give her good advice and give her the skill-set to be able to navigate anything that she lands on.

For me, looking back, it’s like holy shit. I met this crew of fucking kids that were into no drinking, no drugs, and even anti-one night stands. My mom said it was like a parent’s dream. But I can’t control that. I’ve told my daughter about straight-edge, she knows about it, but I can’t really control where she’s going to land. The main thing, I think, is to have the conversations and to be open-minded. I want her to have that open mindset, to have a network of people that you can call at two in the morning and ask for a place to stay. My dad always says that a real friend is someone you can call at two in the morning and say, “Meet me on 125th Street and give me a hundred bucks.” I’ve got a lot of those people in my life, and that comes from being a personable, communicative person. That comes from caring. That’s what I want to try to pass down to her.

Anti-Matter is an ad-free, anti-algorithm, completely reader-supported publication—personally crafted and delivered with care. If you’ve valued reading this and you want to help keep it going, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Photos of Sammy adorned my walls as a kid. In my early vinyl collecting years, every 7", 10" and 12" purchased was cut down the middle and pinned up on my walls and A-frame ceiling (rendering each slab of wax unsellable). BUT, it was more important that I had the collection always in clear sight, above and next to me at all times. Hardcore bands—like all those that Sammy has drummed for—were my greatest influence, my historical artifacts, my blood in my veins.

Thank you Sammy, for years and years and years of incredible rhythm.

Love Sammy's outlook. Love this interview!