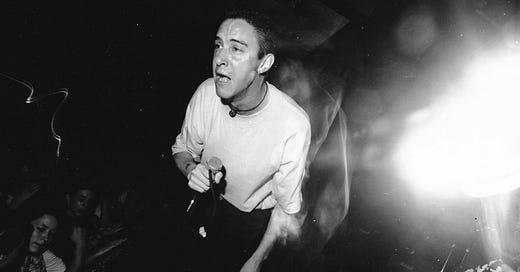

In Conversation: Lou Koller of Sick Of It All

Very few people can access the experience, wisdom, scale, and sheer longevity in hardcore that Lou Koller and Sick of it All have accrued over the last four decades. We must protect them at all costs.

Programming Note: Don’t forget that the Anti-Matter merch presale is only live until July 19. Once the storefront closes, these designs will be gone. Check it out now, and please support this work if you can. (Details for a paid-subscriber exclusive design and discount code can be found here.) Thank you, friends.

Choosing Sick of it All’s Lou Koller as my subject for Foundations Week was a no-brainer when I began the work of conceiving what Anti-Matter’s first anniversary month might look like. Lou and his band have essentially defined the word “stalwarts” as it pertains to hardcore on practically every level; to say that Sick of it All is our most dependable band is basically a truism at this point. Of course, that was in late May. On June 6, when we did this interview, Lou was still almost two weeks away from finding out that doctors had discovered a tumor in his esophagus, and that this tumor was cancerous. It was another mortal reminder in a year of mortal reminders.

There was a moment where I felt like a follow-up interview—an addendum that acknowledged his diagnosis—might be necessary. But as soon as I started to listen back to this conversation, I realized that so much of what we talked about actually resonates more in light of recent events. For one thing, I was able to use my original Anti-Matter interview with Lou from 1995 as a reference map for the evolution of his band and our scene. This only accentuates the fact that theirs is a unique story, one that few bands can tell, about the experience of being a hardcore lifer, about the challenges (and rewards) of playing in the same band for 40 years, and about the economy of aging in a long-running and legendary band. But this is also a portrait of someone whose authentic modesty truly says something about how hard it must be for Lou to be in the position he’s in today—where he is unable to work, where his upcoming tours have been cancelled, and where he’s been forced to directly ask for help. It’s all the more reason that we must support him in whatever way we can, now more than ever.

When we first got together for an interview in 1995, I remember pointing out that Sick of it All had basically outlived every band by that point. And now here we are, 29 years later [laughs]. So besides the fact that it’s shocking that we’re both still doing this, I also thought there was a little bit of poetry here—because not only was that interview 29 years ago, but you were actually 29 years old when we did it. What do you remember about that time in your life?

LOU: We were either touring on Scratch the Surface or writing Built to Last. We were flying high, both as a band and as people. My life was really good at that time. We were met with such a positive response from people all over the world. But the band, that was my life… I also had a girlfriend at home, and she had a child, so he was part of my life at the time.

Your godson. You mentioned him in the interview.

LOU: Yeah! That was a really good thing for me. But touring was all I wanted to do. We were just so into the band. And it wasn’t like we thought we were going to be rock stars. We were naive. We were innocent. We were like, “We’re going to take hardcore and show the world how good it is!” You know? That’s what we thought.

In that interview I asked you how old you were when you went to your first show and you said, “It was 1984”—which I perceived as dodging the question [laughs]. So I asked if you were hesitant to talk about your age. And you said, “No. I just don’t remember because I’m bad at timelines.” Eventually, you did admit that you got paranoid because you were afraid that the kids would be like, “He’s that old? No way, dude!” How has that paranoia developed in the years since?

LOU: Some people still don’t believe how old we are—not just because we’re still doing it, but because of the way we do it. A lot of times people will ask how old I am and I’ll say, “I’ll be 59 this summer,” and they’re like, “You have three times the energy of a lot of bands that are half your age!” I don’t know how to explain it. I really do think that continuing to do the band has kept us young. And at the same time, it’s entertainment, too. I keep in shape. I don’t sit around at home and just eat garbage all day, you know? I mean, look at my brother [Pete]. He’s nonstop. Even on tour that guy works out. I can’t do that.

I’m not so paranoid anymore, but I do still feel a little bit of hesitation when people ask [how old I am], especially in interviews, because I’m always worried about this whole new generation of hardcore that ignores the past. They have their own heroes, which is great; they have their own favorite bands. But when their favorite bands cite us or Agnostic Front of Youth of Today as their heroes, I think they can be more hesitant to check us out because they think we’re going to be a bunch of old men on stage.

I always try to put myself in the shoes of a kid getting into hardcore right now, and I think about how when I got into hardcore it was easy to catch up—the whole thing was only like six years old. But now you’ve got over 40 years to catch up on. Who’s got time for that? [laughs]

LOU: When you put it that way, I get it. But it’s like, we’ve had this situation happen. Even back in the early 2000s, when Furnace Fest opened themselves up to not just being a Christian music fest. They had us, Indecision, Andrew W.K.… And the day we played, Zao went on before us. They were the big Christian metallish hardcore band at the time, and the place was packed to the gills. They were up there saying, “We wouldn’t be a band if it weren’t for Sick of it All. Stick around for Sick of it All.” And as soon as it ended, 90 percent of the crowd walked to the way, way back of the room [laughs]. We were like, wow. This guy just told you that we’re the reason they’re even a band and you’re not going to give us a chance. OK.

I’m curious about how you feel like you’ve been able to handle intergenerational relationships in hardcore. Because the longer we stay in hardcore, the more you have to maintain relationships with people that are going to be much younger than you. That’s inevitable.

LOU: It’s a double-edged sword. Like, I couldn’t wait for the day that people would mention Sick of it All in the same sentence as Agnostic Front and the Cro-Mags and Murphy’s Law. And now because of what some people do online or because of their mentality, there’s a whole generation of kids that are like, “Oh, all these old bands are cavemen.” People can have their opinions, but I don’t want to be just lumped in with certain aspects of being “an older hardcore band.” We’ve always been pretty open-minded. We try to learn from things.

On some level, you’ve been dealing with that for years—even in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. In our original interview, we talked about it a little bit and you called it “the moron factor.”

LOU: I still call it that [laughs].

There really was this group of people back then who saw Sick of it All as a cypher for violence and anger. I always used to wonder if there was ever a time when you thought, “God, if people are going to keep viewing us this way, I don’t know if I can keep doing this.”

LOU: No. It kind of just made us try to prove them wrong. Our music can be angry. But it was never meant to provoke violence against each other. Every time we wrote a song like “Pushed Too Far,” it was about fighting the outside world. That was the thing people didn’t get. It wasn’t about being tougher than the guy next to me or kicking his ass in the pit. It was about saying we’re all in this together, and we’re frustrated and angry, and we’re going to let it out.

Unlike a lot of other bands, Sick of it All never really pushed this narrative that you grew up struggling in the streets. There were no “tales from the hard side” with you. You just seemed like some nice kids with good parents who raised you to respect people.

LOU: Exactly. That’s what it is. That’s the way we were raised in our neighborhood in Queens. You didn’t go out looking for trouble. I think it’s funny that, a lot of times, these people who write songs about growing up hard and all that—they make their lives hard. When we first went over to Europe, we’d meet these guys that looked like they took Agnostic Front and the Cro-Mags and just copied every tattoo, and then you’d find out they come from a farming community in Holland! They’d go out and get into fights for no reason. They’d make their lives tough. There were guys that I knew in Queens like that. I’d be like, “You come from a good family. What the hell are you doing?” But I can understand people mistaking us [for a “tough guys”] if you’re just looking at the photos. Plus, we’re very physical on stage. But when I watch old videos of myself, I’m bopping around like a muppet. I’m not John Joseph-tough or whatever.

I think there’s also something to be said about the fact that you sort of came into the hardcore scene as an outsider. You were a metalhead with long hair at a time where “being a long-hair” wasn’t necessarily putting a target on you yet…

LOU: …And then when crossover started, if you had long hair, you were going to get attacked unless you were in Nuclear Assault [laughs].

Right. And in your book, I counted at least four or five instances where you were called a “faggot”—for that and other things—which made me realize that this outsidery, socially unacceptable feeling that queer people feel is actually as hardcore a feeling as you can get.

LOU: It’s gotta be, yeah.

Which brings us to “Indust.” I was still in the closet during our first interview, but I remember being very excited to talk about this song because as much as I knew that you could be a thoughtful guy, it still felt very meaningful to me that Sick of it All would write a song about AIDS and that you would even include “Silence Equals Death” as a lyric.

LOU: I mean, it’s because, yeah, we grew up in Queens, but we all hung out in the city. As cliché as it sounds, I worked in the theater. I worked for a fashion designer. I was around gay people and trans people all the time. My best friend worked at Patricia Fields at a time when you would walk in and it was all trans women everywhere, working there. And they were the funniest people ever. They cracked me up all the time. They were great. So I had no reservations about this stuff. I had no preconceived notions. But I can’t just give credit to the scene. My mother, you know, she was a child in World War II when the Nazis came in. She would always say, “Never judge people on the way they look. Judge them on how they treat people and on their actions.” And that stuck with us.

It’s still something I’m working through, to be honest, because there was this oxymoronic thinking in the ‘80s that just made me feel crazy inside. It was like, “Fuck prejudice! But gay-bashing is OK” [laughs]. It messed me up.

LOU: Exactly. But even back then, I remember when the Exploited were playing the old Rock Hotel and a bunch of skinheads I’d never seen before were running down the street, chasing some guy because he was gay. We were like, “What the fuck is going on?” But this was the West Side. So we come to find out that there was this big tough leather bar around the corner, and everyone in the bar came out and kicked the shit out of those skinheads. That’s a story I’ll never forget [laughs].

The other day I was thinking about how Scratch the Surface was maybe the first truly traditional hardcore record ever to come out on a major label. But in my memory, I don’t remember you guys taking the same amount of grief for signing as even, say, Quicksand. Is that how you’d say that you experienced it?

LOU: We did get some, but not a lot. We honestly got more shit when we signed to Fat Wreck Chords after the fact—after we got off the major—because we signed to “a pop-punk label.” We did two records for [EastWest]. After that, they sat us down and they said, “We want to talk to you about doing two more albums with us. We like what you do.” They called us a “sub-gold band,” which meant we weren’t making gold records, but they also weren’t losing any money. They made money off us, so they wanted to keep us. But we didn’t want to stay.

It’s interesting to me because it feels like your band, more than any other, really seems to be inextricable from conversations about class in hardcore. There’s this idea that when a band who comes up from, say, upper middle-class roots signs to a major label, there is absolutely no excuse. But for you guys, it was almost like there was a pass, because we all thought, “You know what? They’re working class. They were taught by their parents to work hard and earn their money. And that’s what they’re doing.” On some level, that comports with the way you’ve had this workhorse mentality that you’ve had since the beginning. There wasn’t really this doubt that a major label would change or “kill” Sick of it All. There was just a weird, unspoken consensus that you’re just out there making a living. Do you see any merit to that?

LOU: I mean, maybe not consciously, but that’s kind of what it was. It was just the next step to keep up going, to keep us on the road, to keep being musicians instead of going back to my job at the carpet factory. And I did work in the art department for a carpet factory that made carpets for the super rich in College Point, Queens. I would leave for tour, and come back, and leave for tour, and I didn’t want to do that anymore. One year, going back to 1989, we got asked to do part of the Bad Brains and Leeway tour. I asked my supervisor for two weeks off and he goes, “It’s cool with me, but you gotta go ask the manager of the factory.” So I asked the manager of the factory and he was like, “Well, you have to make a decision. Do you want to have a job? Or do you want to go play musician?” I walked out of the factory that day and I never went back.

Getting on a major label, though, it wasn’t like they handed us a bucket of money and we didn’t have to work anymore. It wasn’t until three years later, in 1997, when I could finally not come home to a job—and that was only because we’d made some money from touring the whole fucking world. We finally made enough money where I could come home and be like, “Maybe I can actually just take a couple of weeks off and then go start writing another record.”

That’s actually something that a lot of people don’t know. You still worked day jobs while you were on a major label. Did that feel like a weird paradox?

LOU: I think we were grounded in the reality that Scratch came out and did well, but it was no fucking Pantera, you know? We didn’t do the numbers they did. So whenever we weren’t touring, I was working in a mailroom. I got Pete a job there. I got Toby [Morse from H2O, a former Sick of it All roadie] a job there. If they weren’t working with me, they were all doing construction. Armand [Majidi] and Craig [Setari] would also do moving, which is a brutal job. But we had to do stuff like that just to keep some money coming in.

OK, let’s switch gears a little bit. Back in 1995, I asked you how you would describe yourself, and you said, “I’m a grumpy old hermit. I like to be alone a lot.” But since then, your life has dramatically changed. You had a family and a daughter, you have people in your life that you kind of need to see. How much of that grumpy old hermit still resides in you?

LOU: He’s still here [laughs]. But also, I moved to New Jersey. I didn’t lose contact with my friends—like, I speak to a lot of my friends almost every day—but I don’t get to hang out with them because they all live in Brooklyn. It’s very rare that we all get together. The hardest part is that [it seems like] you only get together for funerals. There’s that old saying, “All we have left is weddings and funerals,” and it’s pretty much true at a certain age. And then after another certain age, it’s just funerals. Like, I was just at Eddie Leeway’s wake, and I saw so many people that I hadn’t seen in almost 30 years. And they still live in Astoria, still doing what they did.

Does that compel you to see people more often? Because I certainly feel like I’ve been affected by how much death there’s been lately.

LOU: Yeah, I send messages to people. But I think I’m pretty much the same guy [that I was in 1995]. I like to be alone a lot. I like to just go off and read. Or I go to the movies, except now my daughter is my movie partner. She’s fourteen now, and ever since she was eleven, we’ve been going to the movies. Summertime is big for us. When I’m home, we go see whatever new movies are out. Lately, she’s been making me go see romantic comedies. Some of them I really like, but some of them are like, “Just tell the guy that you like them! What’s wrong with you?” [laughs].

You haven’t put out a new record in a minute.

LOU: Yeah, 2018 was the last one.

How do you talk about making new music at this point?

LOU: We really dropped the ball, because as soon as lockdown came, as soon as they shut everything down, we had to cancel all these tours. All the ducks were in a row, it was looking amazing, tickets were selling like crazy, and we had to shut the whole thing down. The promoters were like, “Don’t worry. Just wait two months.” And then after two months, another two months. And it kept going to the point where we all had to go out and get jobs, which really fucking sucked. You try writing a résumé when your last job was in a mailroom in 1997.

Anyway, during that time, Pete started writing. He had something like over 30 songs written. But instead of working on those songs, everybody had to go our different ways. And then when everything opened up again, we were broke. So instead of finishing an album, it was more like, bang, go on tour. We’ve been on tour pretty constantly since the COVID ban was lifted. We have plenty of songs, but we just have to get all four of us in the same room to hash them out. I’d say at least ten of them are album-ready, but we need all four inputs.

How has the recent resurgence of hardcore, if at all, changed or affected your calculations in the evergreen question of, “How long can we keep doing this?”

LOU: I don’t know… Knocked Loose is huge. Turnstile’s success is huge. Has that trickled down on us? Maybe, maybe not. We don’t know yet. I can say that on our last European tour, we did these two festivals, and there were not a lot of 25-year-olds at those shows. They were all sold out, but there were not a lot of 25-year-olds. I jokingly asked the crowd: “Is anybody here under the age of 30?” And you could count them when they raised their hands. So it’s weird, because we’re missing that demographic, I guess you can say, from 16 to 29, even.

I feel like that’s such a different paradigm from how I felt about the older bands when I first got into hardcore. I seemed to have more of a need to understand the people who came before me. Like the first time Kraut got back together and opened for GBH at the Ritz—I was so fucking excited. Or that time Cause For Alarm got back together and played the Ritz with Youth of Today. I was like, “Fuck yes! I get to see Cause For Alarm!” It was a direct connection to history for me. But it seems like what you’re saying is that you’re not really experiencing that.

LOU: Not really. I always joke around about this, but you can equate it to how everyone took that one Hatebreed riff and made a career out of it, and now it’s a totally different style of music. We play fast. But [it’s almost like that means] we’re not hardcore anymore. We’re punk. You know how many people have said to us, “Oh, Sick of it All, you’re punk.” And we’re like, “No, we’re a hardcore band.” And they’re like, “Oh, that’s not hard. This is hardcore!”

I have this friend in California who got out of listening to heavy music for a long time. She went on some spiritual journey or something. But she reconnected through social media, and she went to a record store and said to the guy, “I really loved hardcore when I was young. What are some of the new, cool bands?” The guy picked some things out and she was there with her headphones on like, “This is metal. I don’t want to hear metal. I want to hear hardcore!” [laughs]

I wrote an entire essay once that basically argued that Texas is the Reason is as much “hardcore” as metal is “hardcore.”

LOU: That’s totally true [laughs].

OK, I wanted to focus on something else here for a second. A lot of the conversations that you probably have at this point deal with Sick of it All’s longevity—and that’s one thing. But I feel like we’re not having enough of a conversation about sustainability. Those two things are different. You can have longevity and last a long fucking time on bravado and stubbornness [laughs]. But sustainability takes thought. It’s not a question of “can we last?” It’s more of a question of “how can we last?” Which is a valid question with real answers. In hardcore, I think this is complicated by the fact that I think we operate a lot of times with this assumption that you should suffer if you choose to be in a band. That suffering is noble. That being broke is a birthright…

LOU: Yes!

So I’m curious how you approach this question after 40 years of being a band. How do you go about putting your needs into the conversation?

LOU: It’s a tough thing to deal with. Again, going back to pre-COVID, when we would go to Europe, we would always use a tour bus because we could afford it. We were more popular there. We could do it. But when COVID bans ended, every band in the world was trying to tour—especially in Europe, for some reason. Bus prices were five times what they were before. So now me, at 59 years old, I’m doing van tours in a country where I used to be able to get off a plane, get into a bunk, and sleep as long as I needed. I have to do van tours again. And sometimes I sit there and go, I can’t do this. You’re older. Your body is not what it used to be. I need a lot of sleep for my voice, and it doesn’t bounce back as quickly as it used to. How long can we keep going after this? I don’t know. If it were up to me, we’d be playing three or four shows a week so my voice can recover. I’ve even said I’ll do five shows a week. Just give me two days off every week. No, we’re doing six shows a week. Sometimes it’s five, sometimes it’s four, but mostly it’s six. And by the fifth or sixth show, you’re getting 59-year-old Lou that sounds like he’s going through puberty because I’m screaming over an hour every night [laughs]. So we try to make compromises to keep going.

What are the non-negotiables for you? What do you really need to keep doing this?

LOU: The reality is we need to get paid. I’ve been on a million songs as a guest, and it wasn’t until 2024 that I was like, “I can’t do this for free anymore.” But I still feel guilty asking people for money to sing on their record because I’m like, who the fuck am I? And as a band as well. We’ve been through a lot our whole career, but the story we always point to is when we did a show at Full Force Festival in Germany. We headlined the very first one, played the second and third ones, and then it got really huge with metal bands. So one year we did it, and it was Slayer, Ministry, Sick of it All, and Anthrax. Anthrax went on before us. This was at the height of Scratch the Surface, and we just totally destroyed the place. I’m talking about 50,000 people, and everyone is moving to Sick of it All. We’re walking off stage and Ministry is waiting to go on, and Tom Araya [from Slayer] yells, “Fuck, how is Ministry going to follow that?”

An hour later, our booking agent says, “Come with me.” So we go into the office of the festival, and there’s a chart on the wall with what everyone is getting paid. Anthrax, who went on before us and didn’t get half the reaction we got, was paid almost five times as much as we were paid. So our agent starts yelling at the guy, and they’re all yelling in German. He’s like, “Why the fuck would you treat them like that? You saw what they did.” And the [promoter] was like, “They’re a hardcore band. They don’t expect to get paid a lot.” What the fuck does that mean? So this is something we’ve been trying to rectify over the last few years.

OK, but this goes back to that thing you mentioned a couple of minutes ago. We do, as hardcore kids, have this weird feeling that we should be doing this for free…

LOU: We feel guilty.

Yes. And I think that actually just leaves us exposed to be taken advantage of like that. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. We really do start to feel like we aren’t worth anything.

LOU: On the last tour we just did, the woman who sells our merch told us about this guy in his forties or fifties who came up to the table and was like, “All you guys want is money. Look at your shirts. Why do you charge so much for your shirts?” And she went, “When was the last time you paid to listen to music?” He was just, like, dumbfounded. Nobody pays to listen to music. You can go to Spotify and listen to any record that’s on there. But go to Spotify and try to listen to an audiobook. You get five minutes and then you have to pay. Why can’t they do that for bands? Why is the music just given away?

I feel like this is an issue we really haven’t grappled with from a community perspective, because there really needs to be a repositioning in how we talk about money. We are still talking about money like it’s 1984, and it is not 1984 in a million ways. Even in 1994, I could still make a fair share of album royalties to help keep things going. It was all right. But not anymore.

LOU: Exactly.

So how do we calculate “fairness” now? Because one thing I’ve realized is that while hardcore taught us a lot of things, one thing it didn’t really teach us is that you’re going to get old. And “survival” looks different as you get older. That’s what drives me a little crazy. It feels like we’re bound to some sort of fixed, but arbitrary economy.

LOU: I remember trying to put this tour together in 1998 or 1999 where we were talking to Snapcase and Avail about doing a tour. I remember Daryl [Taberski] asking who would headline—like, do we go by who sells more records? We were like, “We’ll go on in the middle. We’ll go on first. We don’t give a shit. Let’s do this. This is gonna be an amazing tour.” And then Avail was like, “Well, with the three of us, how much do you want to charge at the door? Because if it goes over ten bucks, we can’t do it.” It was like, what? You’re getting the three arguably biggest bands in hardcore at that time all going on tour together, and we’re arguing about that? Even if it was just two of those bands, ten bucks is not enough.

That’s the thing. We have this notion about being “fair,” but we don’t actually have any sort of real agreed-upon criteria for what that means.

LOU: They always bring up Fugazi. Goddamn Fugazi [laughs]. I don’t why, but Fugazi could go, “OK, we’re renting out the Roseland, but only for five dollars a ticket”—and yeah, it worked for them. But it doesn’t work for everybody.

OK, but maybe it didn’t work. Or at least it may have worked out for the band specifically, but the Roseland absolutely lost money that night.

LOU: Oh, especially with the union.

For sure. The amount of people on the payroll that it takes to even open the doors of that place—those people were not getting paid on Fugazi money. They got paid from whatever show happened the night before.

LOU: Or when Nirvana played the week after.

Right. So then the question becomes: Is that ethical? Is it ethical to just name an arbitrary price, get paid, walk away, and let the venue eat it?

LOU: Wow. That’s true. That’s true.

I don’t know [laughs]. I just think a lot about how we had no sense of a future in this when we were young. Even in our first interview, you didn’t think you’d be doing this for another ten years—and yet we are having this conversation 29 years later. We’re all just making this up as we go along at this point. We’re trying to write a future that today’s 20-year-old hardcore kids might look at and say, “Well, damn. Lou and Norman are still in this fucking game. How did they do it? How did they survive?” At 59 years old, what kind of hardcore future do you see?

LOU: A very short one [laughs]. There’s a physical toll, no matter how much you keep yourself in shape. I’m sure there are no 59-year-old football players, at least that I know. As far as the desire to keep going? When it stops being fun. Ninety percent of this is not fun sometimes—like, you know, setting things up to go on tour or arguing about how you’re going to travel because when you’re older you want to be more comfortable. But once we’re together, and even if we’ve been fighting or whatever, when we are together and we go on stage, it’s fun. It’s exciting. We’re laughing at each other or we’re laughing with each other. There’s the audience. That’s what makes the whole thing. How long it’s going to last is still up in the air, you know. It’s all up in the air. I can’t tell you I’d like to do this for ten more years. I don’t want to be 65 and doing this. But then again, we might do another interview when I’m 65 where you’re like, “You said you were going to stop!”

Are you saving money for a rainy day?

LOU: Yeah, but… Like you said, life happens. And it always chips away at your nest egg. So I’m still saving. I’m not rich. I’m still saving.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is CRUCIAL to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

Again, I love the money conversation.

It's tough because I would assume that the vast majority of kids that start bands don't do it with any expectation that they're going do it for more than a few years. They just want to play to their friends at the local DIY space or small venue. They don't care if they play for free if they get to open for their favorite band. And then money slowly becomes a concern because maybe they've been around for a couple years and now they wanna do a little tour, but not because they want to make money doing it, they just want to travel and meet people and hopefully get their gas costs covered.

But now they're growing and maybe their favorite band is offering them to open up a 6-week long tour. What an opportunity to get in front of new people and grow the fanbase! But it's a 4-band package and they're the up-and-comers so they won't get paid all that much. And now it's a few years later and they're headlining their own tours and they can finally start asking for guarantees, but their fanbase is young and doesn't have much money for "frivolous" things like going to a show so they want to keep the ticket price low.

And a few more years go by and now they're in their 30s and some of them have families and they're still touring half the year, but they're working a minimum wage job when they're home to make ends meet. And the cycle continues.

I think another part of the challenge is that hardcore is punk and punk is equated with poor, at least historically, and that anyone can do it. You don't need to have the most expensive equipment or take lessons, just buy a cheap used guitar and have at it.

I don't know where we go from here outside of older punks like me who have decent jobs and can afford to support bands by buying records and merch directly from them or contributing to GoFundMes when someone gets sick or a van gets broken into. That's certainly not sustainable.

I know this is beside the point, but why would a venue like the Roseland Ballroom book Fugazi and agree to the $5 price if they were going to lose money? Why wouldn't they just tell Ian to go kick rocks?