In Conversation: Frank Turner

Despite getting older, many of us still find ourselves in a constant dialogue with our most idealistic hardcore teenage selves. Frank Turner turned these dialogues into an album that needed to exist.

Like other young seekers in the 1990s, Frank Turner discovered punk through Green Day and Offspring before finding his way into the early aughts London hardcore scene, where he played in bands with names like Kneejerk and Million Dead. But after going solo in 2005, unlike everyone else, he went on to have the most improbable post-hardcore story ever: In 2012, Frank sold out Wembley Arena, with Billy Bragg opening for him. His last album, 2022’s FTHC (which stands for “Frank Turner Hardcore”) somehow went to number one in his native England. And when Undefeated, his latest album, comes out next week, he will be able to claim ten solo records and literally thousands of live shows to his name.

All the while, he tells me, Frank has been debating his fifteen-year-old self at every step—and it’s a dialogue that has forced him to examine the personal and political reasons that drew him to punk and hardcore with a uniquely nuanced and occasionally annoyed approach. (Fifteen-year-olds, after all, can be kind of annoying.) Undefeated began as an attempt to memorialize these conversations with his past self, but like most great things, it evolved. More pressing for the now 42-year-old singer was a question: How can we reconcile the inevitability of old age with the forever-youngness of punk?

Last year you threatened to make an album about being in your forties—and you delivered [laughs]. I’m turning 50 in July, and this is the first time in my life, honestly, that I’ve ever experienced anxiety over my birthday. Forty didn’t do it for me, but 50 feels a lot more real for some reason. Did turning 40 give you that kind of anxiety?

FRANK: It did, actually. I barely noticed turning 30, but I was exceedingly busy at that point in time. I think I turned 30 in the build-up to what was my first arena headline show at Wembley in 2012, and things were just going very, very well. But I turned 40 during the pandemic, and not even during the “Wow, isn’t this novel?” bit of the pandemic in 2020, but during the “Jesus Christ, this is still happening” part—and in particular, when the live music industry was still getting repeatedly punched in the dick. So I was sort of up on bricks, basically, and I started getting a little stressed about it. Thankfully, my wife is a calm and sensible human being. She lost her dad when she was quite young in sort of quite dramatic circumstances, which has been a huge event in her life, and she often says, “Older is what you get if you’re lucky.” Or to put it in other words, sure, you’re turning 40 or 50 or whatever, but it’s better than the alternative. Because there is only one other alternative, which is not turning 50. And if one is forced to choose between the two, I’ll choose still being here no matter how creaky my muscular skeletal system gets.

What do you think it was about 40 that broke your brain a little bit?

FRANK: I can remember my dad’s 40th birthday. My dad is a twin, so they had a joint birthday kind of thing. I was pretty on the outs with my dad at that point, but I went anyway because it was sort of a family non-negotiable, as far as my mum was concerned. And I can remember thinking that my dad was very old [laughs]. So, you know, there was that kind of stuff going on. There’s that sense of narrowing possibility. When you’re sixteen, you’ve probably got time to decide that you’re going to be a rock star and fail—and then still go on to be a neuroscientist or a paleontologist or a carpenter or whatever. There’s still time, do you know what I mean? At this point, I’m in the meat of the sandwich of my life, unquestionably. It’s like, this is who I am and this is what I do. I’m probably not going to go into space ever now.

But the thing is, it’s a double-edged sword. Because if you consider these things, if you meditate upon them, then hopefully, you can find strengths and pride in your station in life. And I guess I feel strongly that the consolation of getting older is more of a sense of security in who you are and what you do. Hopefully. But the narrowing possibilities are there.

I think it’s interesting that, on this record, you seem a little fixated on being fifteen years old; you mention it a couple of times. Fifteen was a very consequential year for me, but I wanted to find out where your brain was at that age. Fifteen for you was in 1997, right?

FRANK: Yes, exactly.

Tell me about young Francis in 1997.

FRANK: Well, a lot of what you talk about, which is well-observed, is sort of an evolutionary hangover of the fact that at one point in time I was considering writing a concept record, which would have sort of been a conversation between me and my fifteen-year-old self. When I was fifteen I’d been sent away to boarding school and I hated it with a violent passion. I felt alienated and very out of place, which had been the case for a few years, but by the time I was fifteen, my love affair with underground punk rock was starting to peak. Like, I got a Sex Pistols record when I was thirteen. Kurt Cobain used to talk about punk in interviews, so I was like, “What’s punk?” And my friend’s uncle, who was the only person I knew who knew anything about music was like, “Oh my god, go and buy the Clash and the Sex Pistols” [laughs]. And then there was Green Day and the Offspring and all that kind of thing, and then you filter through NOFX and Descendents, and then you eventually land on Black Flag. It’s sort of a traditional path.

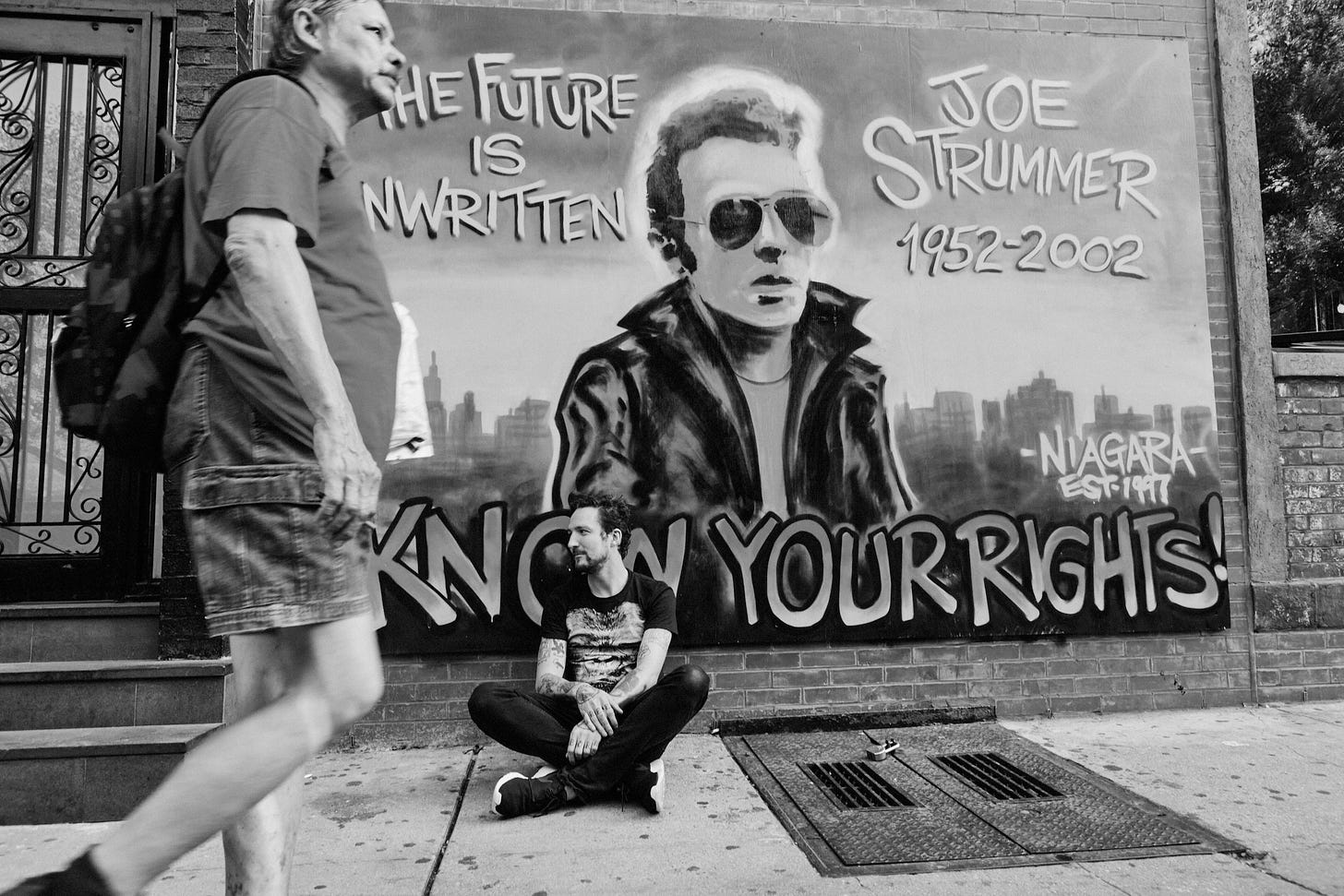

So that was becoming very important in my life at that time, alongside other things—like going vegetarian, I went straight-edge, I started going to lots of shows and got interested in anarchist politics. I was pretty obsessed with Joe Strummer because he also got sent to a boarding school at a similar age and survived to become Joe Strummer, and that was a very useful piece of information for me as a child. But I think the governing thing about that age for me was a startlingly extreme sense of self-righteousness, despite my almost complete absence of understanding of the world. It was like, “I’ve read two books and I now know how the world works. And one of them is by [Noam] Chomsky!” [laughs]. Do you know what I mean? So that self-righteousness and its connection to me now is that I do this thing all the time where I have these arguments in my mind, where I have to justify my choices and my thoughts and my beliefs and my actions and all the rest of it. But a few years ago, I realized that the hypothetical other that I’ve been having this argument with is the fifteen-year-old me—with all his ideals, box fresh and still in the cellophane. That strikes me as really unhealthy. With the benefit of some hindsight, I think the fifteen-year-old me was a pretty damaged kid.

It’s funny because I get what you’re saying when you use the word “self-righteous”—like, yes, I was completely a self-righteous straight-edge and vegetarian kid when I was fifteen—but also, there’s something that was very pure about it. I really did feel like I wanted to do something good with my life, but maybe I didn’t have the wisdom to realize doing good wasn’t a contest.

FRANK: Absolutely. The motives were defensible, and in fact, even admirable. Somebody asked me the other day, “What would you say to your fifteen-year-old self?” and what I would say is: How do you fucking do it? And can I have some of that energy and drive back, please? [laughs] But the flip side is that it’s about the way your ideals and all the rest of it interacts with the real world, and you and I both know that the real world is complicated and gray and shaded at the edges. It’s also worth saying that I was going through some old journals that I was keeping at that age, and it really was kind of pure.

You bring up Richard Ashcroft from the Verve in “Ceasefire,” and when I did the math I saw that 1997 was the year of Urban Hymns. Are we to glean that you had some sort of resistance to Britpop at that age?

FRANK: Absolutely. I have this conversation with a lot of my American friends where it’s like, “I need to explain to you that Oasis were the Nickelback of their era to us” [laughs]. It was just very mainstream, a laddish kind of culture. It was very much the antithesis of any kind of counterculture or independent culture or whatever. There was also this grim sense of irony to the whole thing, which I felt hugely alienating as a kid—that whole, “Yeah, we don’t really mean it” thing. It was this kind of self-conscious cool that I find alienating to this day.

I’ve actually often talked about that kind of disaffectedness—which was a thread through grunge and then into the early 2000s Strokes-styled bands—as the thing that really allowed [second and third wave] emo to happen. I think emo was a reaction to that kind of too-cool-to-care attitude. We responded with over-sincerity.

FRANK: I think that when people discuss my music, one of the central influences to what I do that does not get discussed enough is Mineral, and stuff like that. Mineral remain one of my absolute fucking all-time favorite bands and they are a gigantic influence on pretty much everything I do. But yeah, I think you’re exactly right. The sincerity of it was just hugely appealing to me. I just wanted the art that I consumed to mean something. I didn’t want it to be detached. There is this aesthetic that gets put forward that’s like: “We are inside a very exclusive party. And if you try really hard, then maybe we’ll let you look through the window, but don’t go thinking that you’re actually on the guest list.” I do quite like The Strokes, but they had a degree of that. But I was dorky, ugly, fucking sad teenager. I was not on any cool list. I was not invited to the parties. And to me, that’s what punk rock is supposed to be. It’s outsider art for the people who don’t get invited to the cool kids’ party. That remains pretty foundational to my thinking about it—even for as much that I’m now aware, as I say it out loud, that it’s quite an adolescent vibe [laughs].

When it comes to playing music and being a touring musician, you once said that, even as a kid, you knew you wanted to do this more than anything else in the world. Was there a specific void that that kid thought this kind of life could fill?

FRANK: I think so, but I’m not sure I would have thought about it in those terms at the time. But it was very identity-based, and that’s a thing that adolescents do—they look for ways to define themselves, and that’s perfectly natural. For me, I wanted to be a punk, and I wanted to be a touring person. Those are the two things I was gunning for. And again, in a slightly adolescent way, I’m kind of proud of that. I think that remains a successful achievement in that I am a punk and I am a touring person. So… happy days! [laughs]

There’s a line on the new record [on “Somewhere Inbetween”] where you sing, “I’ve been pretending to someone else since I was just fifteen,” and then a little later you say, “But I remember being underwhelmed when I worked out who I was because that didn’t fit with any of the feelings I’d been feeling.” It’s a very curious lyric to me, so I kind of wanted to go into that a little bit. Exactly who you did you think you were? What was underwhelming?

FRANK: A big part of it is to do with the classic British obsession with class, which is a real thing. I was a middle- to upper-middle class kid with small-C conservative parents who were pretty comfortable with themselves, and I got sent to a boarding school… It is really important for me to say as I say what I’m about to say out loud that I’m aware of how fucking ridiculous it is and how privileged and borderline insulting it is, but I was a kid, thinking, “Why couldn’t I have been born as Cesar Chavez or Che Guevara or someone?” [laughs]. I wanted to be born under more dramatic or romantic circumstances.

Again, I need to preface this by saying that I know that it’s dumb, but when I was around the age that we’re talking about here, I sort of made an attempt to be gay because I wanted to have something on my identity score card that wasn’t just a straight, white, middle-class male, you know what I mean? [laughs]. It was, of course, a pathetic failure and my gay friend—who I’m still friends with now—just kind of laughed and told me to fuck off. It was just a terribly shitty thing to do, but I was just a kid. I just didn’t really want to be me. I think in a large part that had to do with the lottery of birth and how it felt kind of unfair in a lot of ways. There were many, many people who had a harder place to start in life, and I sort of felt guilty, I suppose.

A couple of weeks ago, I published an essay about touring and how it can be an exercise in self-harm, and someone in the comments mentioned [Henry Rollins’] Get In The Van. I responded that I felt like I’d blocked that book from my memory because I hated it so much, even back then. I know that you’ve expressed your love for that book over the years, so I will tread carefully, but one of the reasons I hate it so much is because I feel like there’s this glamorized self-othering going on—which is sort of what you’re talking about here. On some level, that’s what punks do: The way we dress or the music we play or the things we believe create these divisions between “us” and “them.” But that book just felt like a cosplay of, like, who can be more poor? Or who can struggle more?

FRANK: Sure, yes. And I think the word I would use that brings about the elephant in the room for me is “penance.” We’re getting into proper historical sociology here, but when you look at American hardcore… I think it’s definitively American in large part because of its Puritan streak. I mean, straight-edge? Come on. It’s right there. There’s a sense of scourging yourself, and putting yourself through different trials and tribulations, and thereby earning redemption in some way. I can see that all much clearer now as an adult. I also think there are elements of religious impulse that run through quite a lot of punk rock. That’s an unfashionable statement, but I think it’s true. Or to put it another way, there’s a huge crossover between Catholicism and punk rock in the sense that you can be an ex-Catholic, but you’re never not going to be a Catholic. Ditto with punk rock, do you know what I mean? And punk rock guilt and Catholic guilt are very similar.

But yeah, I know exactly what you mean. I feel like Rollins has moved on as a thinker and a writer, but he was very much, you know, “the harder, the better.” There was a real bravado and machismo there, which I think can be quite damaging. There was certainly a point in my thirties when I realized I was engaged in this arms race to be the hardest touring motherfucker in the world and no one else was participating [laughs]. It was destroying my physical and mental health, so I had to do a fair amount of recalibration—and exorcising the spirit of early Rollins from my thinking about the world and myself.

I remember reading something last year about how you were having anxiety attacks and you were starting to deal with issues like that, which on some level, you could argue, might interfere with your narrative of being “undefeated.”

FRANK: Incisively put, yes! And it’s definitely been a thing that has gotten more intense as I’ve gotten older. I did a lot of thinking about what this record was going to be called, and a lot of thesaurusing, if that’s a word, just trying to find the right thing that’s exactly what I meant. And one of the images in my mind when I think of the album title—which is very relevant to what we’re talking about here, and I haven’t gone down this philosophical road before, so I am really interested in this conversation—but it’s Jake LaMotta, from Raging Bull. That is one of the images in my head in that it’s undefeated in the sense of still physically standing, but not necessarily in a “Hooray, victorious!” kind of way. It’s more of a “Fuck you all, you can’t kill me” sort of way [laughs].

I don’t talk about this very much, but a lot of my insecurity with turning 40—this is good shit, I feel like I'm at my therapist!—but it comes around to identity issues again in the sense that I am not the hot, young, new songwriter anymore, which I was once upon a time. I’m not the every-punch-landing, arena-touring sort of dude. I’m in my forties, and that’s not hot, young, cool, and fresh—and there’s definitely this entirely new generation of bands that have come through since. And all of that is to say that I spend a lot of time thinking about where exactly I sit in this world now. I’m about to put out my tenth album. That’s not a sexy number of albums. I don’t want to be a legacy act just yet, thanks very much.

I did a radio session yesterday and the guy was like, “Are you enjoying Texas? Have you been to Texas before?” And I was like, “Oh yeah, I first came here in 2004”—and I immediately realized that was probably before any of the people I was talking to were born. They were so cool, they were so sweet, but it was like like, you can react to that sort of moment in one of two ways: You can either crumple up into yourself and go, “God, I’m so fucking old.” Or you can raise your chin up a little bit. It doesn’t make you a brilliant songwriter or a decent human being, but it does mean you did something with your life.

OK, we’ve been talking a lot about identity. Obviously, I’m queer. So when I heard the story about your father coming out as trans, that held particular interest for me. I know your father came out years before you wrote about it [with “Miranda”]. So I was wondering how did her coming out story affect the way you looked at yourself? Like, what part of her did you see in yourself?

FRANK: That’s a hell of a question right now, my friend. Well, to briefly go back to something we talked about earlier, with real life being more complicated and grayer than you might suppose as a teenager, my dad coming out wasn’t an abstract, contextless development. The context of my relationship with my father, for my entire life, was never physically, but certainly emotionally abusive for a long time; it had a lot of pain and anger involved in it.

Before anything happened with my dad, I would have thought of myself as someone who was pro-trans. So I didn’t object to my father coming out, but it was more complicated than just being like, “Yes! Fantastic!” There was a lot to think about, and I have a lot of issues to do with forgiveness when I think about my childhood. By the way, I still use the words “father” and “dad” and that’s fine with her; she’s also supremely unbothered by pronouns, or at least particularly with her children. But anyway, that’s a sidebar. There was just a lot to process and deal with. My dad clearly had an internal struggle going on that I had no inkling of for a long time, you know. And that thought gives me an opportunity to rethink a lot of events in my childhood with hopefully a little bit more understanding and empathy—more understanding, but not total. Because this is the thing. There are things that are difficult to forgive. I’m doing my best, but again, it’s not simply cut and dry.

This is an odd territory for me to be in, philosophically and psychologically, but I feel like part of my father’s anger at some of the things I was doing as a kid were tinged in some way with jealousy, which is an odd thought, but in the sense that I was pretty adamantly like, “Fuck everything I was born to be, I’m going to be a punk.” I had the assistance of punk as a concept to help me down that road, of course, but I was pretty radically rejectionist of my social and family background. And I think that led to an awful lot of extremely heated conflict with my dad as a teenager. There was a degree to which I think my dad was sort of jealous of my ability to be quite so bold.

This is a whole difficult subject for me because, on some level, somewhere in the middle of all of this, you get to the point of me wishing myself out of existence. Because my dad’s [gender] was not what it was supposed to be. And if my dad had inhabited that properly, if we had lived in a society where they were comfortably able to inhabit that from the word go, then arguably, I’m not here. And that’s fucking heavy.

I ask because I think everyone who has complicated relationships with their parents, myself included, gets to this point where you realize that, ultimately, you still come from them. So like, my parents disowned me when I came out—and that wasn’t the beginning of our problems, that was more the culmination. But it’s impossible not to ask: Where is their reflection in me? Because whether I like it or not, they’re a part of me. So when you have a revelation like the one you had, it opens up a new line of inquiry. It’s like, what does that revelation illuminate in you?

FRANK: I mean, that’s a good question. I know what you mean. Like, my dad does this thing when she argues where she taps the table with her middle finger to make a point, and I found myself doing it the other day. I was like, ah, fucking hell. Are you familiar with the songwriter Anaïs Mitchell? She’s utterly phenomenal, but she has a song called “Little Big Girl,” which is about growing older as a woman, and there’s this incredible line about looking in the mirror and suddenly seeing your mom. It gave me goosebumps. One of the reasons I have a beard is because if I shave my beard off, I’d look just like my dad. This is my camouflage [laughs].

Another aspect of this story that I found interesting is that you asked permission to write about these people and these events, which is honestly something I’ve never really considered as a writer. Or at least I’ve always tried to write in a way that felt like it was inarguably my story. What made you think to ask for permission?

FRANK: The short answer is that I had an incident of writing a song about somebody I knew who took their own life, in a faintly obscure way; it’s a song called “Richard Divine” that was on my third record. But a person who was involved in that event—I’m being obscurant for a reason here—was very upset with me for writing that song, and I think justifiably so. I totally see what you mean, I think we have the right to our own stories and that other people intersect with us, and therefore, they will be discussed. And it’s not like I go get a permission slip for every single song that mentions anybody else saying that it’s OK. But the song “Miranda,” about my dad, involved putting information in the public domain.

Actually, to be specific about that song, I didn’t really give that much of a fuck about what my dad thought about it—and predictably, she was pretty stoked about being the subject of a song anyway [laughs]. But it affected my mom, and I love my mom, and I didn’t want to upset her. So I had to talk to her about it before I started doing interviews about it. To not do that, in that particular instance, would have struck me as slightly sociopathic. And I think songwriters really are sociopathic to a degree.

I have to assume you didn’t approach your father about writing “Fatherless.”

FRANK: No. Or indeed about other songs that mentioned my dad from previous records. I mean, I wrote a song about the fact that I wasn’t talking to my dad, and I did not break this battle by talking to my dad about whether or not I could release it [laughs].

There’s something else I think about when you talk about being fifteen and wanting to be a punk and a touring person, and that’s this: There is no way that kid could have ever fathomed that you would have a UK number-one record or that you’d be headlining Wembley. What happens inside of your brain when you think about those things?

FRANK: I’ve spent a lot of my life feeling like Wile E. Coyote when he runs off the cliff and keeps going. You know, at some point, you’re going to stop and look down and it’s like thew! But going back to the beginning, there have been moments where my punk police fifteen-year-old self has been a little dispirited about some of these things. I mean, getting a number-one record was a really strange thing because a huge part of my self-definition as a teenager was that I was the kind of kid who didn’t fucking care about the charts and didn’t know who was in the charts and didn’t listen to anyone on the charts. So there is a conflict there, for sure, but I try to take it with a positive spin and with a pinch of salt. I went off the edge of my bucket list a long time ago, I guess is what I’m saying. And from there, it’s like, fucking have fun with it, do you know what I mean?

I think, like most sensible people who work in the arts, there is a sense of practical pessimism at work, to where you think, It’s not going to last forever. You just have that in the back of your head. And that’s a useful thing. It helps you plan for the future and diversify and have other irons in the fire. But there’s another thing, too, which is that there are so many people who I started out playing music with, who are as talented songwriters as me and who were just as dedicated to it, and they don’t do this anymore. So I feel kind of morally bound to pursue this as hard as I can sort of on their behalf—if that isn’t a hugely self-involved thing to say. Because so many people I know would have given kidneys to be standing where I’m standing now. So enjoy it. And push it.

I feel like the climax of the journey on this album is in this one lyric [on “No Thank You for The Music”] where you say, “I’m surprised to report, as I enter my forties, I’ve returned to being an angry man.” What I’m trying to figure out is, how do you perceive that anger? What’s actually there?

FRANK: I need to explain this, but I think what I’m really driving at is a sort of self-confidence in a funny way. There’s a certain naïveté required to be as forthright as the fifteen-year-old kid whose ideals are box fresh, you know what I mean? I think I spend a lot of time being paralyzed a little bit by self-doubt and that sense of nuance that you gain as you become older and you become a little bit more aware of the world—that feeling of knowing it’s not as clear-cut as you thought it was. But in many ways, and I’m sure I’m not unique in this, it’s possible for that pendulum to swing a little too far, and you could almost relativize yourself out of having opinions. So having gone through this detour, I feel at this point that I’m coming back to more of a place of saying, “No. I do have opinions about the world,” and I’m regaining confidence in that. Which I suppose is what that lyric is driving at.

That song specifically is about having pride in being a part of the underground counterculture, or whatever adjective that you want to use. It’s about how I am still a punk and still a touring person. I fucking did it. And there’s a sense of reclamation there for me somewhere in this record, to say that I did withstand a fair amount of storms and vicissitudes of life to get to this point. It’s not perfect and it’s not necessarily important to anybody else, but there’s something in the middle of all that that I think I’m allowed to be proud of.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is CRUCIAL to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

I apologize for being "that guy" who feels the need to comment on everything but I find it refreshing that there are people in my age group (40s) that acknowledge that hXc is something that was and still is an important staple in their lives. Plus these interviews touch on subjects that I think a lot about to. (getting older being, anxiety about the future) But I read a great op-ed piece in the New York times the other day from 2017 entitled; "We aren't built to live in the moment" by Martin Seligman and John Tierney. They make a great observation that provided great comfort for me and I hope it does for people reading this; "What best distinguishes our species is an ability to contemplate the future. Our singular foresight created civilization and sustains society. It usually lifts our spirits, but it's also the source of most depression and anxiety, whether we're evaluating our own lives or worrying about the nation" (I know squirrels bury nuts for the winter but those behaviors are all instinctive) But great food for thought anyway.

As I approach 50 and still enjoy going to shows and seeking out new punk/hardcore bands, and still want to be in punk/hardcore bands performing live, I think about age a lot. Within the first few years of moving to Colorado I put out feelers about wanting to get a band going. A few folks got in touch and I was familiar with their current band. That was about all I knew about them. I was in my mid-40s at this point. We met up at a sandwich shop to get to know each other and it turned out they were all still teenagers living with their parents. Now, in the world of punk and hardcore, it's not all that strange for multiple generations of folks to be standing and slamming alongside each other at a show, but when I thought about being this person in his 40s and going to their parents' house for band practice, that was a bridge too far for me. I'm happy to say those kids are all still doing some of my favorite bands in the area (check out Direct Threat with an EP coming out soon on Iron Lung Records). I'm still trying to get that band going but finally meeting folks more around my age to make it happen.

One other bit that caught my eye was when Frank said "I also think there are elements of religious impulse that run through quite a lot of punk rock. That’s an unfashionable statement, but I think it’s true." This is a subject that Damian touches on quite often in his Turned Out a Punk podcast, and I agree. Between the various sects and ideologies and people we idealize and fetishize like deities (Ian, Henry, Ray, Sid, Joe...), there are a lot of similarities.