Shoulder To The Wheel

We encouraged hardcore bands to "tour forever" and valorized their efforts with community respect. But what if we were actually fetishizing self-harm?

I.

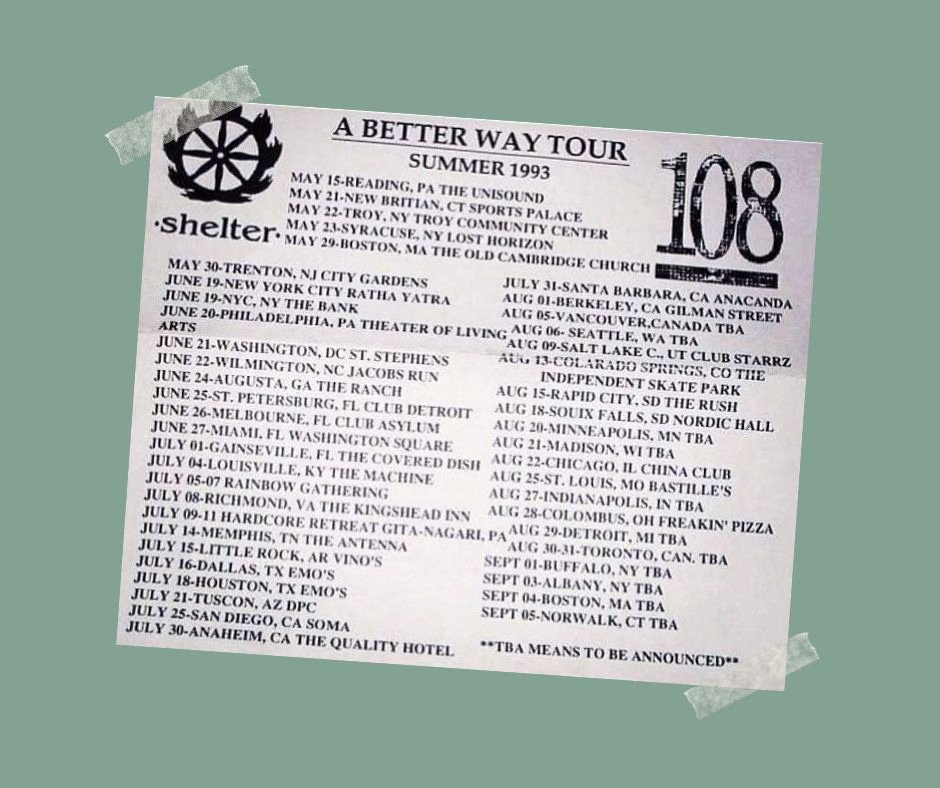

I remember the tour posters we made because, in retrospect, they were peculiar. They were small, maybe 11x17, mostly in black and white, with a single spot color and a disproportionate amount of text. You would think that a tour poster should work to get you excited to see a band—with an oversized live action shot, perhaps—but in this case, we only had so much room on the paper. Because that year, the itinerary for Shelter’s summer tour would begin on May 15, and wasn’t scheduled to end until September 5. That’s almost four months. I call the poster peculiar because the dates alone take up almost 70 percent of the design. There were just that many of them.

The thing that this poster doesn’t tell you, of course, is that we were also scheduled to tour for an additional six weeks in Europe, and those dates began only a couple of weeks later. That makes for almost six months straight of touring—a schedule that feels deeply masochistic from where I sit now, but in 1993, had been at least normalized enough to where I have no memory of anyone in the band objecting to it. Part of that comes from the reality that, at the time, hardcore was in a growth stage that was only beginning to normalize touring in the first place. Before 1990, it was actually rare for all but the most established hardcore bands to do any sort of extensive touring. But by 1993, two clear lanes for bands on tour had begun to emerge: there were “weekend warriors” and there were “road dogs.”

The “weekend warrior” class was comprised of bands whose ranks were filled with members who had other obligations—jobs, classes, or families—that did not allow them to pursue a full-time life in hardcore. These bands toured as often as they could, sometimes sporadically, and many of them were able to do it in a way that lent the impression that they toured more often than they actually did. Bands like Snapcase and Lifetime come to mind, largely because of how much they were able to accomplish with this model. “Road dog” bands, on the other hand, needed to tour all the time in order to come home with any money—and the inverse of that is that they also needed to come home with some money to justify touring all the time.

But more crucial to the “road dog” identity was the way we began to almost fetishize those bands who essentially lived on tour. Sick of it All were somewhat of an archetype for this class of band, and we revered them for what we saw as a deep work ethic that had been baked into their identity from early on—as album titles like Blood, Sweat, and No Tears or Built To Last can attest. Among fans, there was a suggestion that “road dogs” were tougher, that they were survivalists, that they were somehow more hardcore. It was the beginning of a trope that inspired more recent Hatebreed lyrics like, “No sleep, no rest / If that's what it takes to be the best.” These were people who had dedicated themselves to “the life.”

In 1993, I thought I wanted this level of dedication. But what I discovered, even at only nineteen years old, is that this kind of constant travel actually worked to destabilize everything I knew about my young life. I ate poorly and infrequently. I spent almost half of my days physically confined to a seat in the van. I allowed my relationships back home to deteriorate. And I let my mental health go wildly unchecked. As it turned out, touring, for me, did begin to have a survivalist aspect to it, but it was a literal one: This kind of life, I realized, can kill you.

II.

As hardcore has grown—and as the internet has made independent touring more viable and accessible than ever—any number of new lanes have opened up beyond the “weekend warrior” / “road dog” binary, but that isn’t to say that these identities are extinct. Incendiary is perhaps the best-known band taking a hard line against the demands of being an artist that tours incessantly; when we spoke last year, singer Brendan Garrone said simply, “You can’t say it with any certainty, but man, I don’t think we would still be a band if we were touring full-time this whole time. There’s no chance.” In a lot of ways, Brendan wears their “weekend warrior” stripes with pride.

By the same token, Keith Buckley—whose last band, Every Time I Die, played the part of “road dogs” for several years—almost looks back on his experience with horror. “Having been off the road for three years and looking back on my life, I can’t believe anybody survives,” he recently told me. “I can’t believe there aren’t more raging alcoholics. I can’t believe there aren’t more divorcées. I can’t believe there aren’t more single dads struggling. And I can’t believe there aren’t more options for therapy or for Alcoholics Anonymous. There are so many people that I think must have the same problems that I had.”

One of those people, no doubt, is Scott Vogel from Terror. With a 23-year history behind his band, Scott has spent a consequential amount of his life on tour, and at one point in his career, it was an established fact that Terror were committed to being particularly brutal “road dogs”—so much so that, in an old press release for the band, a former label literally bragged that Terror took “a nihilistic approach to touring.” Make no mistake: This kind of hyperbole is an expression of our outdated fetishization with unhealthy touring. It’s an example of the way we often chose to praise bands who were potentially hurting themselves. For his part, Scott now admits that this “nihilistic approach to touring” led to his nearly annihilating himself.

“Everyone who knows me well knows that,” he tells me, in a conversation that will be published in full on Thursday. “I’ve done 30-day tours where I was blackout drunk for 20 of those days, I was just drunk for eight of those other days, and on two of those days I couldn’t drink because I would die if I did. That’s a little extreme, but it was close to that… But it’s funny because now I’m on the other side of the spectrum—and everyone in Terror much prefers this—but now I’m, like, up in the morning. I wake up at like seven or eight o’clock and I’m ready to go. I have a list of things to do and I’m getting them done. Go, go, go. We’ve been fortunate enough to be on a BandWagon [RV] on our last U.S. tours, and I clean it every day. I clean the toilet, I clean the sink, I sweep or borrow a vacuum cleaner from the venue. I do my laundry every couple of days. I’m getting a haircut every couple of days. I compensate for the lack of hangovers with over-energy. I do yoga every day now. It’s a completely different world.”

I remember back in the Warped Tour era, hearing about how certain bands—for some reason, Avenged Sevenfold comes to mind—turned their box trucks into personal gyms, with free weights and benches designed for exercising on tour every day. Many of the bands I was friends with at the time sneered at this sight; in an odd paradox, it would appear that working out made these bands look “weak” at best, or like “meatheads” at worst. But what if the meatheads had it right this whole time? Which bands might still be together if our community had chosen to valorize taking care of yourself on the road over killing yourself to live?

III.

There are maybe only a handful of songs in the punk and hardcore canon that capture the “road dog” experience without completely fetishizing it. Pup, for example, sings: “Seeing your face every morning / One more month and 22 days / If this tour doesn’t kill you, I may.” I’ve been there!

In “Gypsy Panther,” Against Me! sings: “Coming home feels like surrender, feels like we’re giving in / When the shows are over, is there any other reason to live? / I’m just desperate for a little bit of home right now.” I have definitely felt that!

Meanwhile, Jawbreaker’s “Tour Song” asks the question that most of us have asked when we are on a tour that, quite frankly, sucks: “Should I feel grateful to play? / I’m living life my way.” Most days I’d still say yes, but this question is hard!

Interestingly enough, seven years after the six-month tour that culminated with my quitting the band, Shelter added their own contribution to this canon—a song called “In The Van Again”—and re-reading the lyrics now, it certainly feels the most conflicted of any of these songs. Despite his attempts at romanticizing the experience, for one thing, Ray Cappo doesn’t really seem happy to report that he’s on a fourteen-hour drive where no one is sleeping. And even though he concludes that “this whole time I felt so free and learned more in the end,” Cappo also doesn’t exactly leave you with the sense that “trading in the university for this backseat and poverty” is supposed to sound like a good thing. If anything, the lyrics to “In The Van Again” read more like a resignation to the road than an homage to it—and for a bunch of former “road dogs,” maybe that’s the most appropriate response of all. True survival, after all, is a long game.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Scott Vogel of Terror.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is crucial to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

Reading this reminded me of Some Come Running by Bane.

"I'll keep getting in the van / Worry about money for the rest of my life / Just so that you can have this to talk about"

Reading the full lyrics now, I see it about the importance of live shows while recognizing the real challenges it places on the artist.

IMO, a lot of people read books like 'Get in the Van' and romanticized them. This also coupled well with the way we treated "sellout" as a 4-letter word in the late 80s/early 90s. The more hardcore you were (literally or figuratively), the better. The 2nd order effect was a fan base demanding more and more from a band while also not wanting them to have any sort of large scale success.

I know I'm not saying anything new here (especially to a musician that lived it!), but looking back at it, it all seems so upside down and contradictory.

And while I'd like to think that mindset has largely been left in the rearview mirror, one only has to read the backlash Wednesday got when they talked about their SxSW experience a few years ago to see that it is very much alive and well.