Your Band Could Be Your Life

“Be yourself” has long been the rallying cry of a hardcore band. But what happens when being in a band runs away with your sense of self?

I.

I struggled all week with whether or not to talk about this. But I’ve decided that not talking about these things is part of the problem.

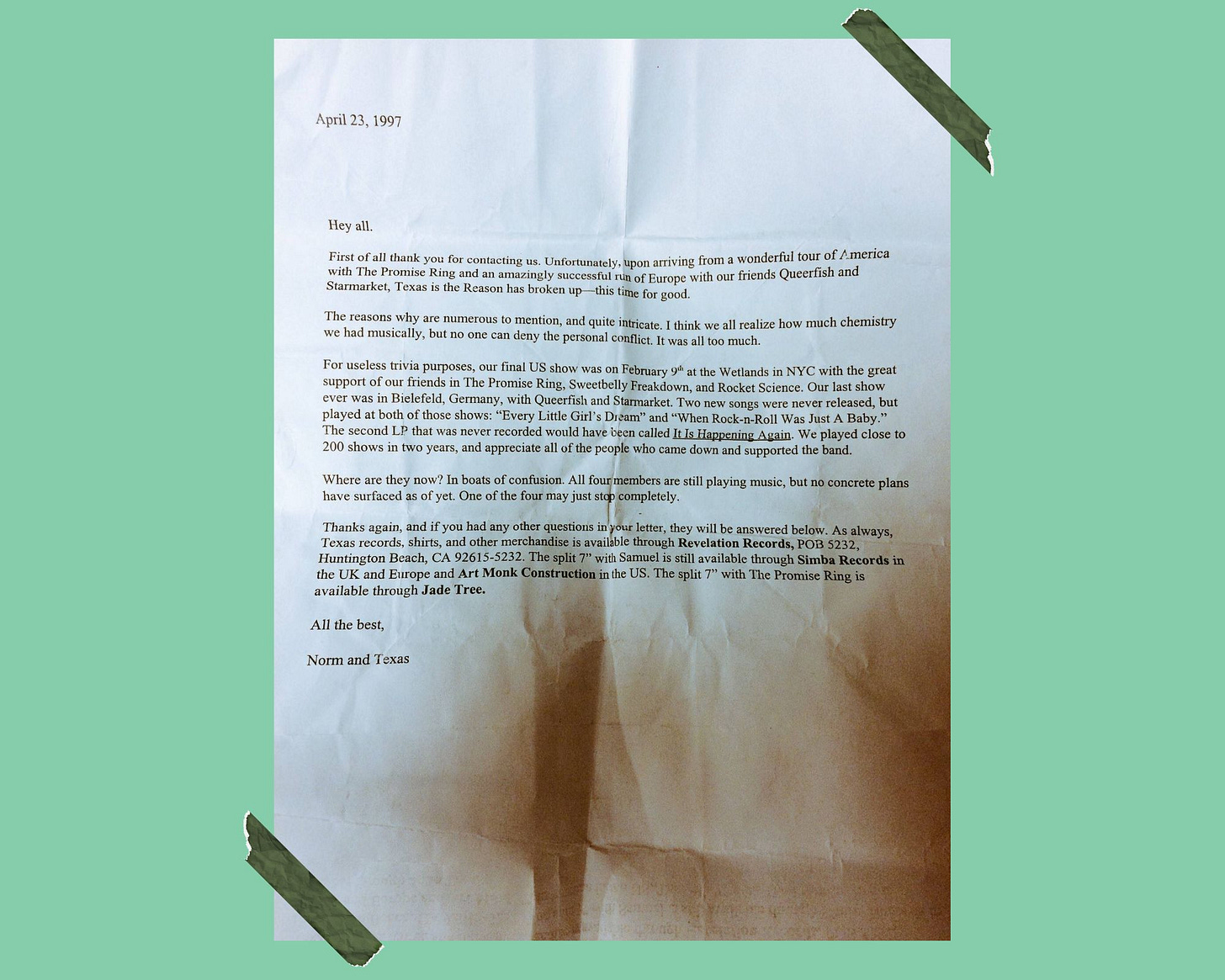

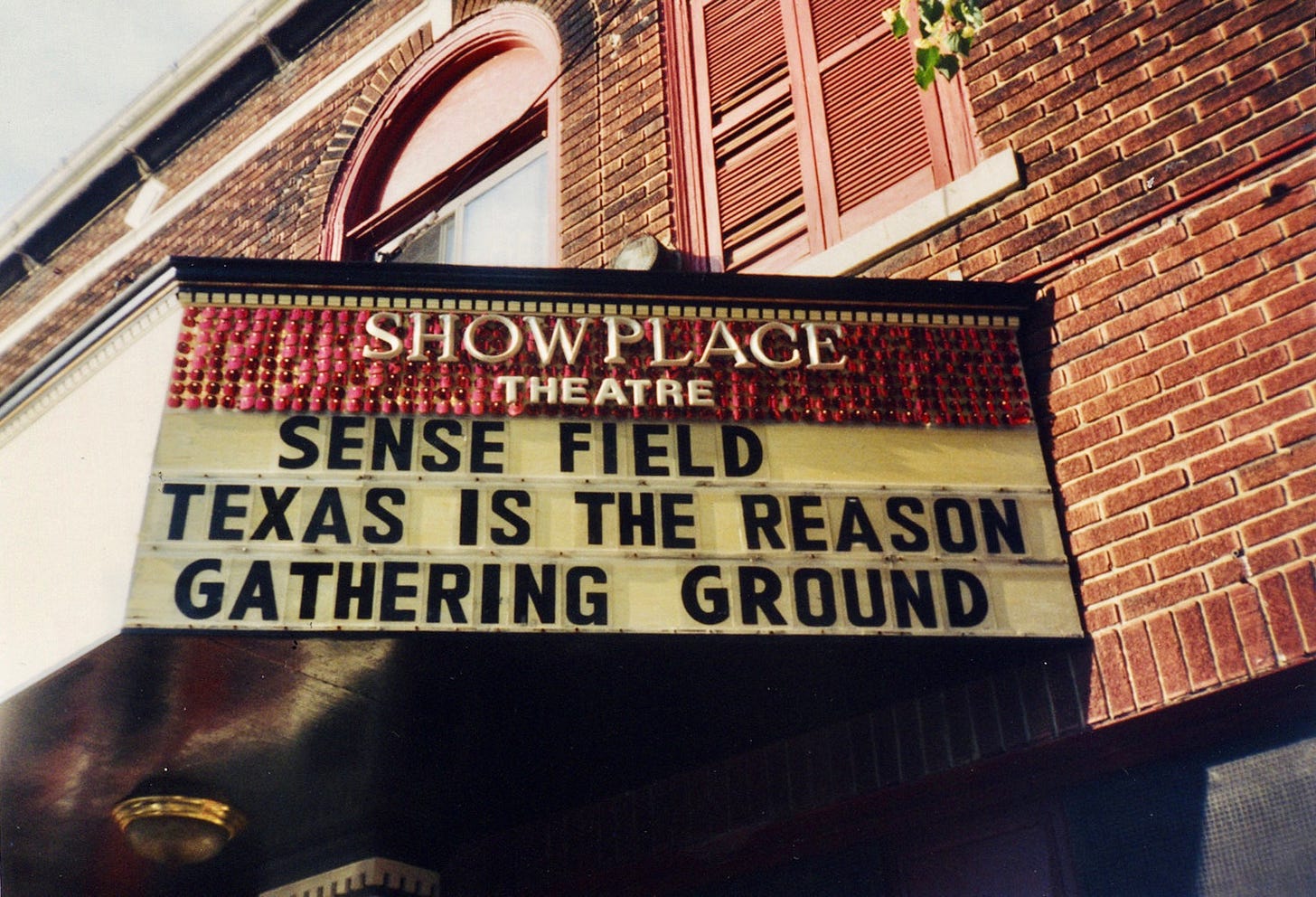

Back in the summer of 1996, Texas is the Reason and Sense Field left together for a comprehensive tour of the country. Both bands were riding high: Sense Field had just released Building—which would eventually be upstreamed through Warner Bros. as part of a recently signed record deal—and Texas had just released our debut album for Revelation that April, which was already being well-received beyond our expectations. The shows were selling out, the energy around us was electric, and both bands seemed to be on the precipice of something.

At one point on tour, our band came up with a plan to trade one member of Sense Field for one member of Texas is the Reason to ride in each other’s vans over every long-distance drive. Camaraderie was important to us for some reason, and that strategy felt like the best way to integrate our touring parties. I remember our drive with Jon Bunch the most.

Bunch was a tall guy—six-foot-six, if I had to guess—so his physical presence was clearly felt in a 15-passenger van. He was also insanely charismatic, which often meant that his psychological presence was just as big. It was almost no surprise that he could sing the way he could; there was a sonorous and near-melodic quality to the way he told stories. In music and in life, Jon Bunch made you want to listen. We all loved him so much.

After a while, the conversation inevitably turned towards our bands, and how we had both begun entertaining possibilities that could never have occurred to us when we started. There were certainly music industry people in our ears, assuring each of us that we were the chosen ones—the next big things who would “break” the way Nirvana broke. We all joked: That’s what they tell everybody. And they do. But we were also on a tour that seemed to be corroborating the idea. Texas was still somewhere in the middle of our climb—and the response to our sets only became more enthusiastic as the tour wore on—but Sense Field was high atop the mountain. It was not uncommon for people to say that Sense Field shows were borderline religious in 1996. People danced and people sang and people cried, much like they do at church. There was every reason to believe this was happening.

There was no reason, at any rate, for anyone to believe this wasn’t happening. But on that van ride, when I asked Bunch what he’d do if they didn’t make it, he responded in a way I’ve never forgotten.

“We will make it,” he said, looking at me with the incredulous look of someone talking to a flat-earther. “There is no other choice. We’ve worked too hard. We’ve put everything into this.”

Sense Field did “make it” beyond our scene to some extent, but not immediately and not at any sort of life-changing scale. Six years after our tour together, their song “Save Yourself” experienced some real commercial success—appearing on the Roswell soundtrack and earning them a performance on The Tonight Show—but it wasn’t enough to keep the band from breaking up a couple of years later. Over the next ten years, I hung out with Bunch on multiple occasions, but there was always a restlessness about him—a waylessness, even—that made me feel like he really wasn’t exaggerating that day in the van. He was tired. He really had put everything into it.

The last time I saw Jon Bunch was in January 2013, at Revelation 25 in Chicago, where our bands had the privilege of playing together one last time. I was sitting in the hotel lobby after the show when he came downstairs and sat down next to me. He said some extremely generous things about Texas is the Reason—things I’ll keep private, between us—and then expressed some sadness about what he felt had been an untapped potential for Sense Field. I told him that if there hadn’t been a Sense Field, there wouldn’t have been a Texas is the Reason. I told him that all those wonderful things he just said about our band were only true because Sense Field made them possible. I told him that our bands both “made it” in all of the ways that truly matter.

“I just really want you to know that I love you,” Bunch told me. We hugged goodbye.

I don’t want to be reductive. I don’t want to insinuate that any of this was “the reason” we lost Jon Bunch in 2016. This kind of thing is complex and never easy to pinpoint—believe me, I know. But I also can’t help but think about the way in which Bunch appeared to internalize everything that the band went through as a reflection of his own identity. And I can’t help but think about that conversation in the van, in which there was only one possible future, and all other options were unacceptable. But most of all, I know how this kind of thing can bring you to the edge because I’ve been to the mouth of that river and I know where the current takes you.

II.

Much has been made of Incendiary’s decision to be a “part-time band,” for lack of a better term. Almost every interview and podcast with them that I can find covers it to some extent, and it’s always spoken about in the most peculiar terms. Because whether we realize it or not, there is an unspoken expectation that being in a band means “going for it,” whatever the cost. It means personal and professional sacrifice, families and finances be damned. It means letting the band drag you wherever the band gets dragged. Incendiary’s model of being in a band is quite the opposite. And while they are far from being the only “part-time band” in this scene, they do seem to be the most visible one to have drawn hard lines around it.

“We’ve made the choice in our heads and in our lives to not be a career band,” Brendan Garrone told me, as part of an interview that will be published on Thursday. “And when you make that decision, it can be very liberating… [Because] I am not interested in what it takes to be in a band in 2023. I'm not interested in being able to pay my rent based on whether or not a Spotify employee decides to put me on the Titans of Metalcore playlist. I don't want to do vlogs. I don't want to worry about what to post. I don't care.”

While the general idea behind his sentiment isn’t exactly new, it is something we’ve arguably never heard before from a contemporary band at the scale of success and level of opportunity that Incendiary has. Which is, perhaps, why so many interviewers are endlessly fascinated by their decision: Because this one choice means that there are dozens, if not hundreds less decisions for the band to make. It means there are dozens, if not hundreds less hours worrying about things that don’t really matter. They just write songs, make albums, and play shows when their lives will allow it.

There was something else that Brendan said about this, though, that stayed with me.

“I just don't feel the need to be out there enough to become ‘Brendan from Incendiary,’ where that’s my persona, because that’s not the only thing about me,” he said. “I do a lot of other things.”

Which is to say that the problem with being “Brendan from Incendiary” isn’t the basic identification of it, but the unintentional formation of an identity that is subsumed by your membership in a band. That’s the thing about “going for it” and letting the band drag you wherever the band gets dragged: Things can happen so fast that it’s easy to lose sight of who you are.

The other problem, of course, is that most bands don’t last forever. And while it’s one thing to be repeatedly identified by what you do, it’s quite another thing entirely to be repeatedly identified by what you did. It fucks with your mind and it puts you into a place where you start to question the value of your own life—as it is, independent of your past. In my case, by the end of 1997, it got to a point where I didn’t even want to go out anymore because no matter where I went or who I met, people insisted on referring to me as “Norman from Texas is the Reason” every single day. It was death by a thousand papercuts.

“Please stop,” I would plead when it happened. “The band doesn’t exist anymore. I do a lot of other things.”

But it didn’t stop, and the psychological schism only made me more depressed and isolated and unhealthy—which, combined with everything else I was dealing with, took me to the mouth of that river. I can only tell you that when I decided to stop being “Norman from Texas is the Reason,” I was trying to save my life. And with that goal in mind, I impulsively packed up and moved from New York to Chicago in 1998 where—gratefully—everyone let me be Norman again. Chicago gave me my self back.

This is part of the liberation that Brendan is talking about, even if he has nothing else to compare it to right now.

III.

The likelihood that a majority of you are in bands is low, so I’d suspect that most of you have never considered much of what I’m saying. But I’ve decided to talk about this because it’s real and because I’ve watched so many friends fall off this boat without a life vest. We need to be able to talk about this.

While playing music has certainly held an outsized role in my public life, in the last 20 years I have also valued my time and experience as a partner, a godfather, a writer, a college educator, a Buddhist, a mentor, an activist, and a friend to many. But while only four of the 49 years I’ve lived on this planet were spent as the active guitarist in Texas is the Reason, I still feel like so much of my social identity—and my identity in this scene—centers that short, but admittedly intense episode as the one thing you need to know about me whenever I walk into a room. It took me years to work out the fact that it’s actually possible to be simultaneously grateful for that band and aware that a band doesn’t need to swallow up everything else about me. If I’m being honest, it also took years of therapy. But I can honestly say that I’ve finally reached a place of peace with it. My personal Instagram account, for example, features occasional memories of Texas, but it’s not a shrine. These days, as much as possible, I try to stay in the present tense.

I believe we have a responsibility to each other in this scene. The problem that I referred to early on is a mental health issue, and it’s something that we actually have some power to mitigate for each other. I realize that hardcore bands are often the first to run towards stoicism and claim they aren’t being affected by the universal experience of growing up in public, but in an age of persistent online scrutiny (and, let's face it, self-promotion), few of us will walk away from this unscathed. So what can we do for each other?

For one, be conscious. Even if the friend you’d like to introduce to someone is literally named “Freddy Madball,” give him a second to be Freddy first. Let that person decide how and when (or if!) they want to disclose their creative or professional projects. Give that person a chance to identify themselves, in whatever order they feel is truest to who they are right now.

It’s also important to check our assumptions. The business of being in a band—even a hardcore one—can bring out some wild conjecture that can actually fuck with a person’s self-worth. Not that long ago, when I was looking around for some work in between tours, an acquaintance told me, “It never occurred to me that you have to work. I always thought you just made music for a living.” As someone who has very sporadically only “made music for a living,” this assumption perplexed me first and foremost. But it also reminded me that so many musicians do keep up a bit of a facade about their need to work, and often fail to correct people about the reality that even some of the most outwardly successful tours and albums don’t actually generate the kind of “real” money that keeps you truly financially afloat. Many of us do, in fact, have to find other kinds of work to make ends meet, and we need to be told that this is not only OK, but that it’s actually awesome to do a lot of other things. I’ve managed record stores, hosted a TV show, and sold a preposterous amount of real estate with the singer for Cause For Alarm, to name just three.

Finally, sometimes only seeing “Brendan from Incendiary” or “Norman from Texas is the Reason” or “Jon from Sense Field” can make it easy to forget that Brendan, Norman, and Jon are real people. The internet has made it easier than ever to dehumanize each other in ways I couldn’t have even imagined in 1996, so I feel like it’s now more important than ever to humanize each other—repeatedly and intentionally. On a practical level, this might mean to lower your expectations: Being the first person to complain on a band’s tour announcement because they are skipping your town, for example, doesn’t take into account that someone in the band might only get two weeks off from work or that any one of them might have personal obligations or health needs that factor into a tour routing. If nothing else, we can all stand to give each other the benefit of the doubt more.

I’ve often said that Anti-Matter was based on a conviction I have that we all keep different versions of the same secrets, and I still believe that’s true. A healthy hardcore scene must be a place where we can feel safe to “be ourselves”—and be a place we are able to return to should we ever lose ourselves.

How Brendan and Incendiary have chosen to run their band is clearly a preemptive strike against all of this, but it’s not foolproof, and not everyone is in a position to make the same choice for themselves. So it’s all we can do to make sure that every one of us is able to see multiple futures, where every decent option is an acceptable one. We must not forget that we are all so much more than what we do.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A far-reaching conversation with Brendan Garrone of Incendiary.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

First, let me say I've been looking forward to anti-matter coming out all weekend.

I'm really struck by some of the last lines, that we need to ensure we can all envision multiple futures. While ive never been part of a band, I've worked, and quit working, in entertainment and broadly, its a field extremely susceptible to the passion tax. We already live in a culture that pressures people into defining themselves by their work, and anything field with a creative pursuit, something driven by real belief, is so easy to lose your identity to. I'm watching the multiple strikes happening right now across entertainment and non entertainment fields, and I am reflecting on how many of my favorite bands have burned out or broken up, in large part because of the increadibly extractive labor practices in touring music. There's not a one-to-one parallel here, but as someone who values music, I'd love to help build a culture where we prioritize individuals' health and well being as much as the music they produce. Thank you for another thoughtful and eloquent piece.

I remember Nathan Gray freaking out online about his new band The Iron Roses and how all the press was "Nathan Gray from BoySetsFire's new band!" And how much he hated that "from BSF.." I was one of those folks who wrote it up like that and didn't get it. "This is who you are!" I thought to myself.

But reading this puts it into such a different mindset and perspective that i didn't see before. How having that "From..." tag might hurt you in ways i didn't understand.

This was a real eye opener and I'm looking forward to that interview.

Thanks for opening up my eyes, this morning. ❤️