Young ‘Til I’m Not

When hardcore was young, there was no one old enough to show us what a hardcore future could look like. What does it mean when that’s no longer true?

I.

While going through some old issues of Anti-Matter recently, I noticed there was a short stretch of time where I seemed to be going through a peculiar fixation with age—or at least with getting older. It’s a topic that crept into conversations with everyone from Sick of it All’s Lou Koller (a mere 29 years old at the time) to Mike Judge (only 27). Admittedly, I often brought it up because I knew it was a site of vulnerability, and perhaps tellingly, it was always received as such. Back then, no one ever spoke about aging in the hardcore scene as a point of pride or an opportunity to grow into a new role in the community. Aging was something you did in silence, which is probably why everyone winced whenever I asked.

I need you to know that when I interviewed Lou and Mike, I was no more than 21 years old. But I had been going to shows since I was 13, and I was already feeling like “an older kid” with a deep uncertainty about the future. Hardcore had been my entire life. But whenever I tried to find any practical representations of “hardcore adulthood”—whenever I just tried to imagine what a future in hardcore might look like—the images were vague at best. Even Ian MacKaye, who was born to play the role of an “elder statesman,” was only 32 when he appeared in Anti-Matter. (As an aside: At one point I asked Ian whether or not he was “set for life,” and that is as clear a sign as any that I had no idea how long life could actually be.) So when Patrick West asked a 21-year-old me about my own approach to aging in an interview with Change fanzine in 1995, I spoke to him about an “older hardcore man” that I’d seen around town much in the same way someone might talk about a mythical creature:

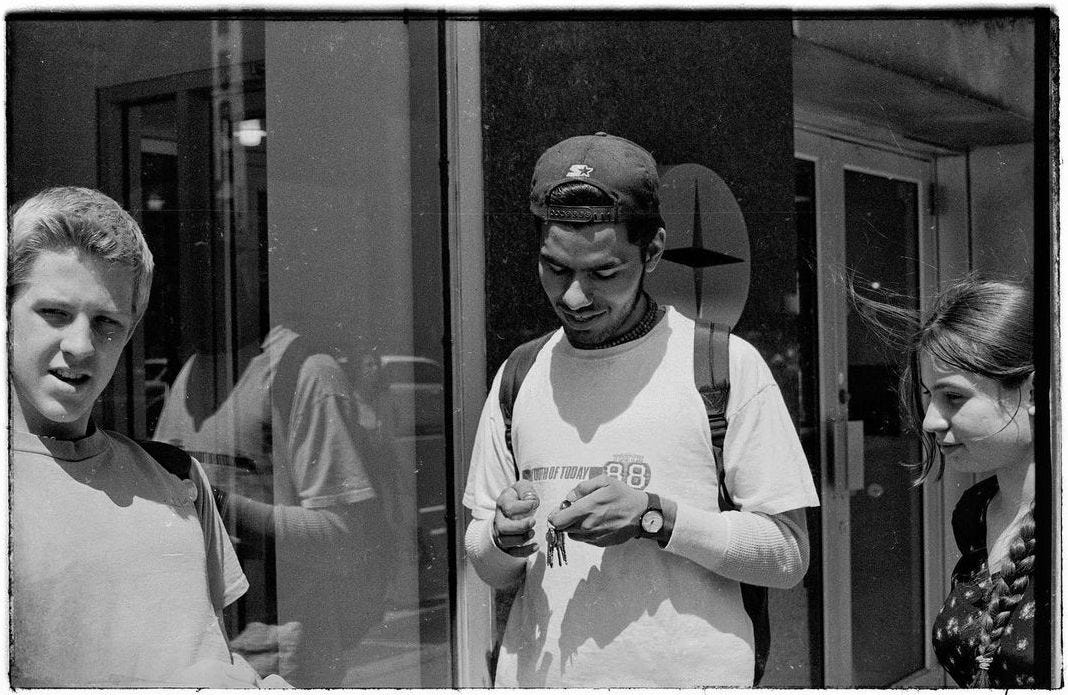

You know this one guy from Long Island who comes to shows? He’s gotta be 40 years old by now. He goes to shows and he wears the same two shirts over and over again—a “Nazi Punks Fuck Off” shirt or a Gorilla Biscuits shirt. At a show in New Jersey, a bunch of friends started asking him questions about his record collection, and he was like, “I’ve got every record you’d ever want. I saw Teen Idles!” We were completely blown away by this guy. Now, I don’t know if I’d want to be him when I’m 40, but I wouldn’t mind being connected to the punk scene in some way. Right now it seems like [I’m] either gonna be punk or monk.

When I read this now, I first want to say that I am astounded by my complete lack of imagination. For one thing, I chose to assign this man with being “40 years old” because that age was simply unthinkable to me. But going back to it now, was this man even 40? Not necessarily. Teen Idles existed for a short blip in time, from 1979 to 1980. Which means that even if our “older hardcore man” was 18 years old in 1980, he would have still only been 33 at the time of this interview.

But also, how awful was I to say, “I don’t know if I’d want to be this guy when I’m 40!” All “this guy” ever did was go to shows and use whatever “grown-up” money he had to buy records and t-shirts and zines at the merch table. He kept to himself most of the time, bothered absolutely no one, and did his best to contribute to the community in his own way. All he ever did was support a scene that he loved—even if that scene seemed to favor the young in a way that may have actually marginalized him.

Lou and Mike are now both in their fifties, still active, and still playing shows for thousands of hardcore kids of all ages. Last week I turned 49. I, too, still play in a band and what you’re reading now is literally a reboot of the fanzine I started when I was 19. None of us could have ever foreseen this.

II.

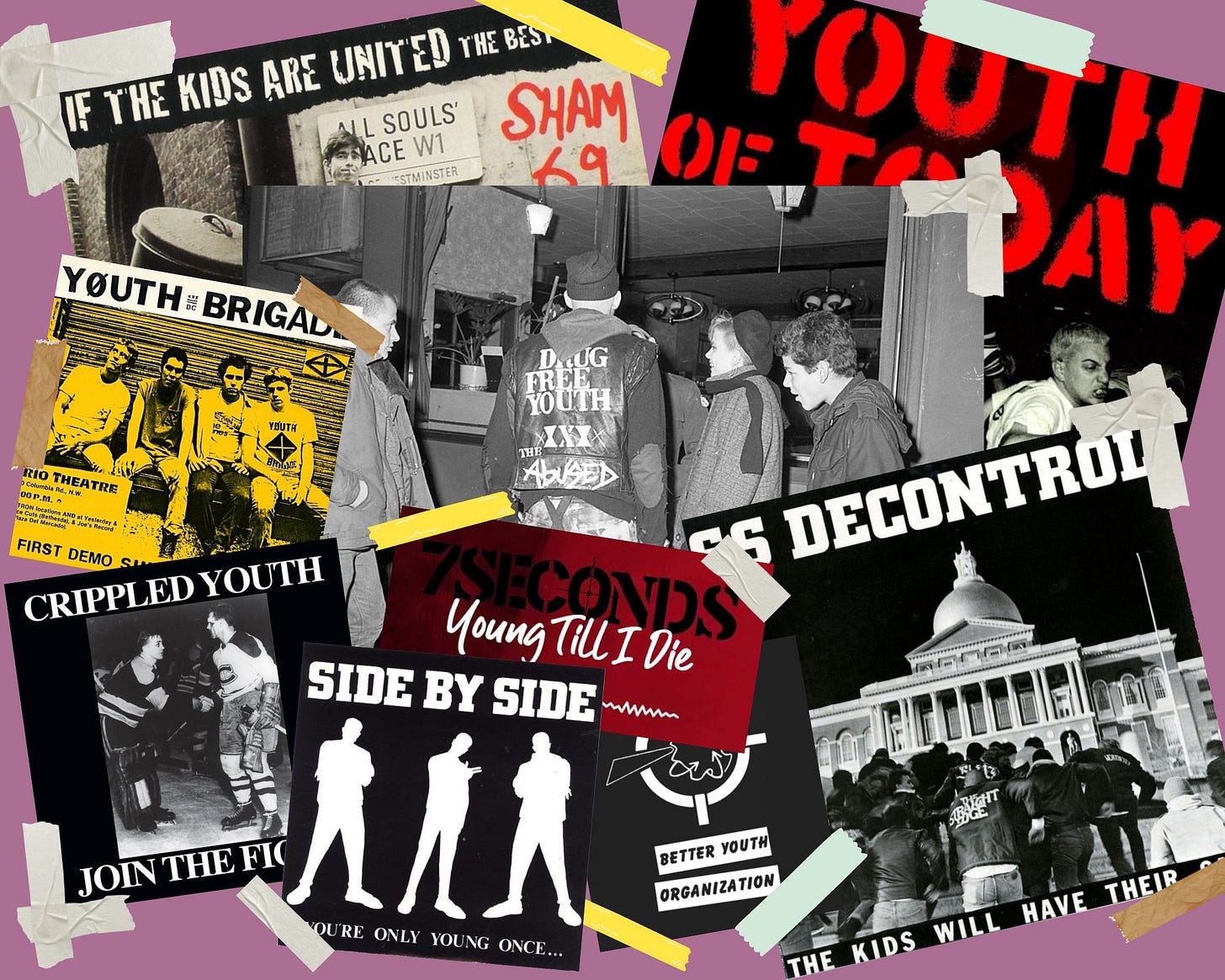

They say language reveals the preoccupations of its speech community, and if that’s true, there are no greater words in the hardcore lexicon than “young,” “youth,” and “kids.” The sheer number of bands, songs, and albums that have used these words in the last forty-something years of this scene is so incalculable, it’s pointless to even list them. You know them. You own the records. You still sing along to them, no matter what your age. Off the top of my head, I can name no less than two completely different punk songs called “I Don’t Want to Grow Up”—one by the Ramones, the other from the Descendents—and I have to believe there are dozens more. Even the primary term we use to identify ourselves—as “hardcore kids”—speaks to the absolute reverence we’ve given youth: The “kid” is the ideal.

To be fair, this development probably owed more to circumstance than design. In the first fifteen years of hardcore, the majority of people at the shows were young. And the “grown-ups” of that era, the baby boomers, really did make adulthood feel like a far and distant future for many of us. In our minds, boomers were hippies who gave up on their idealism or Reaganites intoxicated by their own affluence. (Ironically, Teen Idles articulated this point in a particularly adolescent way.) There were lots of things that actually separated us from the boomers, of course, but age became the most useful signifier for that gap. We believed that, unlike the hippies, hardcore would be the youth movement that didn’t fail.

The good news? We have triumphantly outlasted the hippies by decades. But we also created a system of mixed messages and a culture of discomfort around aging that has probably done more harm than good. We internalized dozens of songs that position adulthood as a poisonous end, and not a powerful start. We used the word “mature” as a slur, and—in spite of the wealth of songs that we love dedicated to the notion of “change”—we reflexively approach change with suspicion. The 7 Seconds anthem “Young ‘Til I Die” still inspires fist-bumps and singalongs, but really, what are we actually saying?

III.

There’s a story I like to tell about a young man I met on tour with New End Original in 2001. A small group of us were hanging out after a show in Florida when this guy came up to me and started a conversation. It was a perfectly good chat, and he honestly seemed like a really smart guy. As we started wrapping up to go back to the hotel, he shook my hand and thanked me. He told me there had been another hardcore band—friends of mine, in fact—who had just played at this club, and his exchange with them didn’t go as well.

“They treated me like I was 16 years old!” he said. “You didn’t.”

I curiously asked him how old he was.

“Oh, I mean, I’m 16,” he laughed. “But I don’t like to be treated as a kid.”

Whenever I’ve told this story in the past, I used it to show how the gap between generations had been widening, and how—even though I was only 27 in 2001—I was already starting to fear that I was “aging out.” I thought hardcore was a young person’s game, and that maybe I’d been holding the ball for too long. Telling the story now, I realize that the scourge of ageism in hardcore actually worked both ways: This young man actually thought there was such a thing as being too young.

I thought about this story a few weeks ago when I sat down with Mike Judge for another interview, our first in 29 years. There’s a part in the conversation where I ask him why he seemed so exhausted when we spoke in 1994, why he talked to me like his life was over. We laughed about it, but his answer rang true for me.

“I never thought I would have been doing it at 27,” he said. “Not only that, but I thought that by the time I was 27, no one was even going to care about anything I did. It just didn't register with me. I mean, it’s crazy now that dudes can make a career out of it and keep going and Judge can play and all these bands can play and people show up. I wasn't expecting to get past 27.”

The hardcore scene gave us so many things, but when you are hyper-focused on being young, staring at the future is a bleak proposition. At 27, Mike and I both thought we were looking at the end of a tunnel, with no way out. We didn’t understand that it was our job to dig deeper and leave a passage for the people behind us. We failed to grasp that it was up to us to invent the hardcore futures we couldn’t find—if not for us, then for the younger kids, still looking.

As I write this it’s not lost on me that the chorus of New End Original’s biggest song is, “I never want to say my best days are behind me.” Nothing encapsulates the feeling of that moment any better.

IV.

At this stage in hardcore’s story, it seems necessary for us to reevaluate the symbolic value of “youth” and how we use that word to convey certain qualities that aren’t necessarily age-specific: Idealism. Courage. Commitment. Loyalty. Fun. As someone who grew up in this community and took these ideas to heart as a teenager, I know that these aren’t characteristics you need to outgrow in order to function in the larger world. If anything, my understanding and appreciation for these things have only deepened with age.

It also feels necessary to embrace the fact that hardcore’s iconic “all-ages shows” are, perhaps for the first time in history, truly all ages. We should be finding ways to take advantage of this incredible cross-section of energy and experience and perspective, and we should reflect this multiplicity in the language we use.

There’s a fundamental Zen Buddhist teaching I love that, I’d argue, embodies all of the things that hardcore has historically attributed to being young, while being wholly applicable to young and old alike. It says: “In the beginner’s mind, there are many possibilities. In the expert’s mind, there are few.”

I’m still here because every show can feel like the first one. I’m still here because we deserve endless possibilities.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A 29-year reunion interview with Mike Judge.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

This essay rings true on every level. I was introduced to the scene as a senior in high school, super involved for years, but eventually faded as I entered young adulthood. A few years back, Knocked Loose came through OKC and I went. That show and environment completely galvanized my love of the scene. Now I’m the 35 year old school counselor wearing Kublai Khan TX shirts to work.

Hi Norman, been a long time! Cool article. Glad to see you're back to writing again. That's something I need to ramp up again. But I'm still here, over 60 and still getting out to shows, doing an on-line punk radio show and taking lots of photos. I think ageism is definitely an issue and it goes both ways. People of my generation denigrating the youngsters and them wondering why we're still sticking around. In my case, it's because being involved in still fun. And I do think it's cool that people just getting into it are interested in learning the music's history. There's a lot more I could write but I just wanted to say hello...