Unlikely Sources: Max Bernstein

He currently plays guitar for the biggest pop star in the world, but New York City's hardcore scene is where Max Bernstein first discovered himself.

Welcome to another edition of Unlikely Sources, a recurring feature where I invite creatives from different walks of public life who are not typically associated with their love of hardcore to choose and discuss three hardcore songs that have some personal meaning to them. This month, I’m speaking with Max Bernstein.

You may not know Max by name, but over the last fourteen years, he has played guitar for some of popular music’s biggest names including Miley Cyrus, Demi Lovato, and Kesha. His current job has him traveling the globe and playing stadiums with Taylor Swift—whose Eras Tour is projected to become the highest-grossing tour in history.

Before all that, though, Max grew up in New York City, where he found himself immersed in the local hardcore scene as a young child after a chance meeting with his nanny’s boyfriend—who happened to play in a popular New York hardcore band—quite literally changed the course of his life.

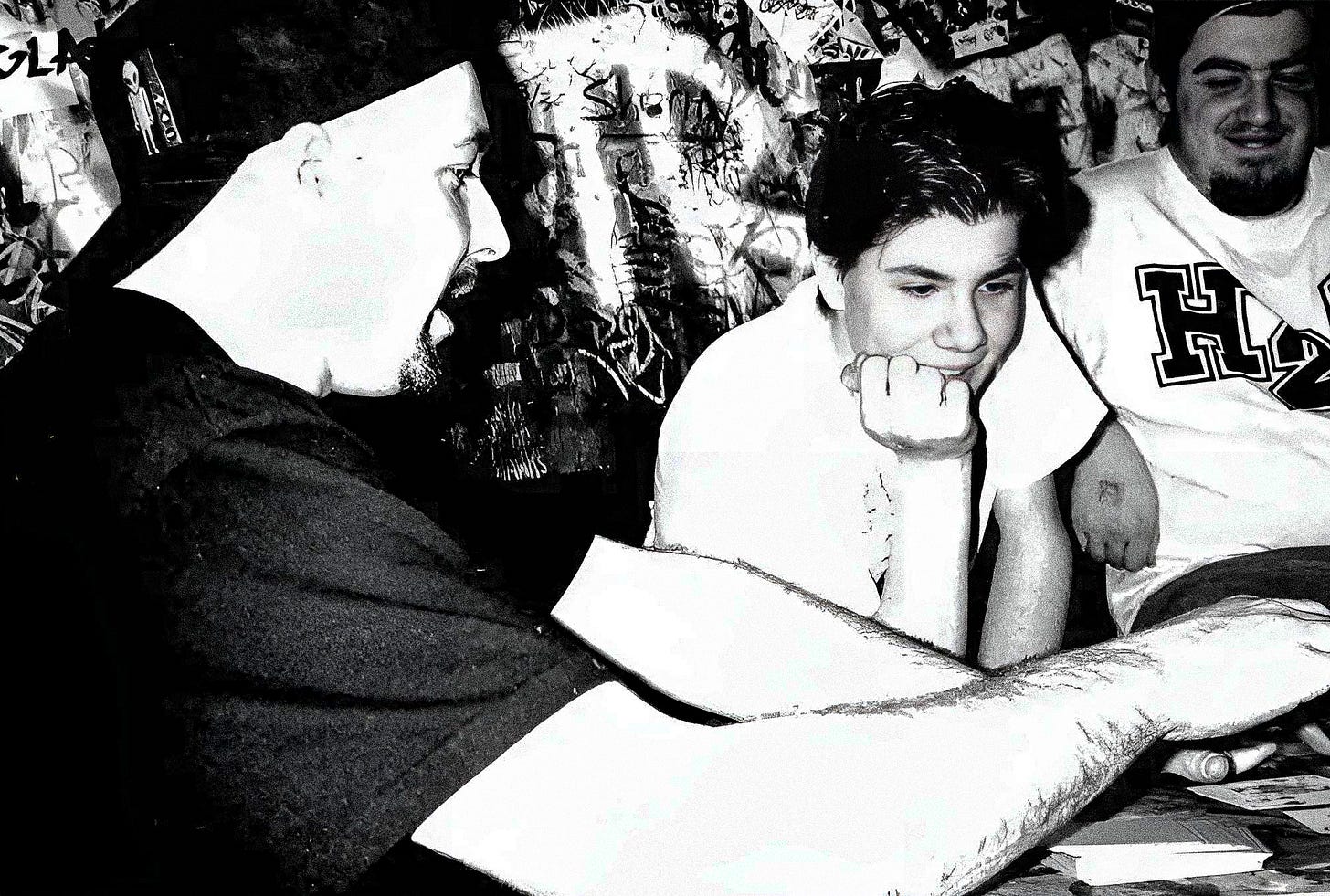

How does a 14-year-old kid end up playing cards at CBGB with Keith Huckins? You look young as fuck [laughs].

MAX: That was one of the first Kiss It Goodbye shows. I knew those guys at first because I volunteered at Reconstruction Records and Keith was one of the people who volunteered there, so I got to know him. I loved Rorschach and Deadguy, so when they started the new band, I went to see a bunch of their first shows. I was an excited 14-year-old, getting to the show early, and I knew how to play poker.

I feel like you’d have to be a pretty enterprising kid to want to volunteer at Reconstruction at that age.

MAX: I don't know what it was like for you when you were a kid and discovered hardcore, but for me it felt like, in one day I went from knowing nothing about it to hardcore being the only thing I was interested in—and it was all through one person. This started when I was eleven years old, and my brother and I had a nanny whose boyfriend was in a hardcore band. It was Marcos Siega from Bad Trip. Marcos just made me into his little brother, and he brought over a crate full of records. I played guitar and I liked what I saw on Headbanger’s Ball, so he did a “Listen to this, not that”—and that’s what I did.

Was your entry more through ABC No Rio then?

MAX: Well, I went to Recon and then ABC would have shows at three in the afternoon on Saturdays. So we would walk from Recon to ABC.

NAUSEA “Fallout (Of Our Being)” (New York City Hardcore: The Way It Is, 1988)

This might be a good place to start then, because I feel like the connection between ABC and Nausea runs deep.

MAX: I never saw Nausea, but Neil [Robinson] was always there selling records; he had his Tribal War thing. They had just broken up really recently when I started listening to them. I had the Revelation comp, which also had a different version of that same song on it, but I think the first thing I got was the Lie Cycle 7”, which I bought at Recon. I believe it’s Neil singing on the Rev one and then it’s Al on the later one. To me, that’s my favorite of their songs. It’s just too bad because they’re a cooler band with Amy on the songs, and she’s not on this song, but this was just their opus to me.

I think one of the things that really stands out about Nausea to me was that they just had this completely cohesive identity—as people, as a band, in their art and graphics. They were so strong in who they were, and I think that’s why they showed up on the New York City Hardcore comp. Because even the average hardcore kid at that time was like, “This band is fucking legit.”

MAX: That comp was probably the first time I heard all those bands and they immediately stood out as being different. Like, there was no machismo with that band. They were political and they clearly meant it.

How would you describe your connection to that song?

MAX: Well, guitar is a big part of the songs I picked because I’ve been a guitar nerd since I was a kid, and I feel like there’s this idea that punk and hardcore is not flashy guitar playing, and while it’s not [about that], it’s clear from the second you listen to that song that Vic Venom is a monster guitar player—all the whammy bar moves, it’s so confident and searing.

But my family was always political. When I was in fifth grade, we were marching down Broadway protesting the Gulf War, we were going to Greenpeace events, things like that. The lyrics to that song, which are just simple, basic, lefty activist punk was easy to understand and I was drawn to it right away. I still like a lot of the bands I liked when I was twelve, but some of it feels like you need to be very young to enjoy it or something. Nausea is not like that. Their music has aged really well, and I think that’s why people still listen to them.

Wait, didn’t you wear a Nausea shirt on the Howard Stern Show? Wasn’t that a thing?

MAX: I wore a Nausea shirt, but it was under a jacket [laughs]. I could not believe this. OK, for one thing, I was deep in Covid fear—this was pre-vaccination—so I was wearing an N95 mask and a face shield. It was pretty insane, but I was being overly cautious for the first bunch of months. So no one knew who I was on that. It was the first show I’d ever played with [Miley Cyrus], and I’m wearing a jacket and there’s only a little bit of the Nausea logo sticking out. But I get home from Howard Stern at like ten in the morning or something, and someone tagged me in a thing that John John [from Nausea] posted. Everybody was like, “Oh, some stylist!” [laughs]. Then Neil posted something, and I was like, “No, Neil, this isn’t the Nausea shirt I bought from you at ABC No Rio, but it wasn’t a stylist.”

HÜSKER DÜ “Indecision Time” (Zen Arcade, 1984)

Where does Hüsker Dü fit into your hardcore awakening?

MAX: They came a little bit later for me. I started listening to them more when I had a band and everybody told us we sounded like them and I hadn’t heard them. This was when I was fifteen or sixteen. But I started listening to them and immediately I was like, “Oh, this is the music I want to listen to.” They’re probably my favorite band of all time. Everything I want music to be is all put together in that band. They have aggression where warranted that is completely primal. There’s melody and harmony that’s far beyond what you’d have expected from a punk or hardcore band at that time. They’re a three-piece, which is always my preferred format for a band. There’s nothing in between [Bob Mould] and the music, and the guitar is just this conduit for every bit of that guy. And I was always drawn to the grandiosity of concept albums; I never stopped listening to Rush, I still love them. So when I heard Zen Arcade, it was just all put together into one thing. Everything I wanted for music was on that record.

I wrote an essay recently for a book coming out called Negatives, which sort of covers the second and third waves of emo. And in it, I am more or less trying to speak for those of us from that era who do not fit into that stupid trope that people have of the “sad white boy crying about a girl”—meaning people of color, queer people, and trans people, who have been also doing this stuff. One of things I say is, “Could emo have even been called into existence without the arrival of Zen Arcade by Hüsker Dü?” I don’t think so.

MAX: I don’t think so either. And Zen Arcade would not be what it is if Bob Mould and Grant Hart were not gay [and bisexual]. Both of them have talked about it. They’ve both said something to the effect of, “How could anyone have not figured it out listening to that album?” [laughs]. That record has more emotional maturity than any hardcore record that would happen for a while. That was 1984. It’s not like this was going on in ‘87 or ‘88, right as Fugazi was starting to stretch things…

It was even before Rites of Spring. This was happening at a level that maybe people took for granted at the time.

MAX: When you read about them at that time, like in the chapter about them in Our Band Could Be Your Life, it was really clear how much they were outliers among their peers. They were just so different from the hardcore bands they were playing with in every aspect. But yes, I don’t think there’s emo as we know it without this record.

Is that sense of being an outlier something you felt at all? How much belonging in hardcore did you feel?

MAX: A lot. For me, I got into hardcore at the perfect time. It was funny going back and listening to these songs. I had a hard time choosing. I went back and forth between Dag Nasty and any number of 7 Seconds songs. It made me think about why hardcore appealed to me so much when it did. I looked so young for my age. When I was thirteen, it looked like I was ten. There’s a picture of my entire class in my ninth grade yearbook and it looks like a ten-year-old snuck into the photo. My friends were growing up faster than me. They were getting into drugs and alcohol faster than me. They had girlfriends before I did. It was all very alienating. So there was something about the more positive hardcore bands—like Gorilla Biscuits and 7 Seconds and Dag Nasty—that I related with. It was sort of embracing the wholesomeness of childhood that’s in that music, and yet it was aggressive, which I was. That’s what hit the spot for me.

And it feels like even though you were young and you looked young, you still seemed to find a community.

MAX: Yeah, and I think there was something too about the fact that everybody in that community was older than my friends from high school. I was like, “Oh, you guys think you’re all grown up, huh?” [laughs]. There was definitely an aspect of being psyched that I had different friends that were all older than they were, and that we were into this whole thing that they weren’t part of.

How did your parents feel about that?

MAX: I think they were oblivious to it. They knew I would go to this record store on Saturday and then come back in the late afternoon. And they loved Marcos, so that made them approve, I think. He signed off on it. Marcos also later introduced me to my wife, so he has definitely had an outsized effect on my life.

DAG NASTY “Circles” (Can I Say, 1984)

You said you were going back and forth between Dag Nasty and 7 Seconds. Why did you go the way you went?

MAX: Guitar is a big part of it. Brian Baker’s playing, especially on this record and on this song, it’s so confident. It’s almost delicate. When you listen to the difference between the Dag With Shawn version and the Can I Say version, you hear how much he refined the parts and made it into this perfectly constructed part. The lyrics are very young, and it’s the kind of thing where if I heard this song now for the first time I don’t know if I’d relate to it as much, but when I was young, I did.

Another thing though, when you go back and listen to the Dag With Shawn version… Shawn Brown is not as “good” a singer as Dave Smalley, and it’s better. His performance has way more gusto to it. The only time I saw Dag Nasty was four years ago, I think. They played at Alex’s Bar in Long Beach, and it was the Shawn Brown lineup. It was what you wanted to hear. You want to hear Dag Nasty as they became better players, playing incredibly, with Shawn Brown singing. It’s like, I want to hear the Can I Say album with Shawn Brown’s vocals as opposed to those demos one day [laughs].

OK, but let’s put Shawn to the side for a second. In the Dave versus Peter Cortner fight, where are you staking your claim?

MAX: The Peter Dag Nasty… I like it, but it was never as big of a thing to me.

I am the only one who prefers Wig Out, huh [laughs].

MAX: There are songs on Wig Out that I like! I’m going to go listen to Wig Out again tonight. But you know, I listened to Can I Say that first week—the week that Marcos brought his records over. That was one of them. And it sounded the most like music I had already heard, in a good way. It sounded enough like R.E.M., the Go-Go’s, U2. Stuff like that is all in that band. They were one of the only bands in that crate who had a really good melodic singer. So it was very accessible to someone new to the genre, and that song, you can be a frustrated boy about anything at the age of twelve and that song will hit.

How do you think about this part of your musical history and taste in context with what you do for a living?

MAX: That’s a good question. It’s hard to say because when you play other people’s music for a living, most of the job is just doing the assignment. But as a player, I think that whatever is good about my guitar playing comes from playing along with those records when I was a kid.

A lot of what I do when I’m not on tour is… I am what’s called a Musical Director. When you make a [pop] record now, there’s a bunch of producers programming their own stuff, emailing tracks to other producers to finish it, and everyone is playing their own things. But when it’s time to play live, you have to reverse-engineer a record that’s been kind of made to listen to on a telephone to make it work in a live room; you do new arrangements of songs—that’s what being an MD is. You’re creating arrangements that make the song work better in concert. I have a little bag of tricks that I pull out all the time, and so many of those come from punk and hardcore songs. I use this thing where I have the bass drop out for half a chorus and then come back in… That’s from “Unfulfilled” by Quicksand. That’s where I got that trick. I use it all the time. I mean, going into a half-time part? It’s a hardcore breakdown [laughs]. Everything that I know is going to work to excite a room comes from being at those shows and seeing those bands do those things.

From where you sit, how do you perceive the little ways in which hardcore seems to be moving into the pop world? Like, even in terms of someone like Post Malone shouting out Scowl or Militarie Gun. There are things like that where it feels very “what the fuck is happening?”

MAX: I mean, it’s amazing to see Turnstile become this huge band. I think they’re great. I think the amount of jealousy among some people who dislike that band is so insane. Hardcore is as old as Buddy Holly was when I started listening to hardcore. And I feel like people who are our age are used to it being this thing that not a lot of people know about. But at this point, Minor Threat is… It’s canon. Everybody has heard that at some point. It’s in the DNA of all popular music at this point.

Genre is really fluid right now, as you know. You talk to eighteen-year-olds about what kind of music they like and they’re like, “What are you talking about? I like music.” The tribalism that we grew up with is so gone. Like, the idea that “we like punk so we can’t like metal.” That’s gone.

Do you still identify as a hardcore kid? Do you still see that in yourself?

MAX: Yeah, absolutely. The music that makes me feel the most is the stuff that I listened to from when I was 12 to 21, and so much of that is hardcore that it’s just a part of me. Any other music that I get into later, I have to learn. I spent a lot of time learning how to play country music well—probably more time than I spent actually playing real hardcore. It is not a part of me at all. It’s not a thing that I feel inside of me the way I do with hardcore. I identify as a hardcore kid because of that. It’s the most in me.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

I saw Greg Norton (and buddies) play last night and he mentioned Max in a conversation afterwards. This is a GREAT interview! Can’t wait to tell my daughter about this. 😁

I met Keith Huckins a couple months ago. NYC, Dillinger reunion, night 2 with Deadguy. It was unreal!!!