Too Tough to Die

There was a time when "being hard" was a matter of immediate survival for hardcore's urban pioneers. For the rest of us, there are other ways to show your strength.

I.

I was eleven years old the first time I ever had to fight someone. My older brother had essentially set me up: He asked a neighborhood kid to step to me at our local park with the intent of provoking me in some way. Then, according to the plan, when the two of us were in close proximity and the moment was hot, my brother’s job was to surreptitiously push me into that kid—in a way that would read as if I were the aggressor. Pressured to respond, the neighborhood kid was forced to throw the first punch, and just like that, my brother manufactured “a fight.”

So I threw some punches and I took a few. The whole thing couldn’t have lasted more than a few minutes before my brother—also artificially—broke it up. He had seen everything he needed to see, but more importantly, the neighborhood saw what he felt they needed to see.

“You didn’t back down, you handled yourself, you didn’t get fucked up,” he told me later. “I needed to know you weren’t a pussy. And now the neighborhood knows that, too.”

I can’t say if the fight had anything to do with it or if it was entirely in my head, but it’s true that even the kids I didn’t know in the neighborhood seemed to treat me differently after that day. I didn’t particularly like violence, but I hated being a “sissy” more. So I kept fighting. A little over a year later, when a kid at my new school on Long Island called me by the N-word in a gym locker room, I punched him in the face, too. I needed him to know I wasn’t the one, and now my classmates knew that, too.

I was fifteen years old the first time I threw a punch at a hardcore show. It was 1989, and I had been hanging out mostly with a gang of skinheads and skaters who were known for their readiness to fight. With them, I’d already gotten into a few brawls outside of shows—in a Burger King parking lot, at the Sunrise Mall, on the front lawn of a kid who mouthed off to our de facto “leader.” Inside of our little crew, I was sometimes jokingly referred to as “MC Hammer” for carrying a literal hammer in the inside pocket of my flight jacket. I never used it in a fight, but I still cringe at the very real possibility that fear could have driven me to make an irrevocable mistake at that age with a weapon like that at my disposal. It was stupid. I was stupid.

I don’t remember who was playing that night. We were at the Sundance—the same Long Island club where I went to see my very first hardcore show a few years earlier—when I saw a guy almost twice my size running straight for me. That would have been normal except for the fact that he was doing it in between bands. No one was playing. No one was moshing. Somehow I was able to stop him with my hands and somehow I was able to throw him to the ground. As soon as I saw him land, something in my head clicked, and I became that boy in the park again. I braced myself for his return, and once he made his way back to me, we punched each other in the face a few times before my crew arrived to intervene. They threw him back to the ground, where they proceeded to beat him.

The pattern continued: People in the scene seemed to treat me differently after that night, as if I’d earned some kind of respect in the process. But this time, it didn’t feel so good. I was beginning to realize that I didn’t care if anyone thought I was “soft” anymore. By that point I knew who I was well enough to know that I was basically a nerd in skinhead drag. I listened to the Cure and read Oscar Wilde. I kept a diary and watched Small Wonder. Acting “tough” created what I thought were some necessary protections to exist in my neighborhood, in school, or in the hardcore scene, but it wasn’t actually who I was at all. It was stupid. I was stupid.

II.

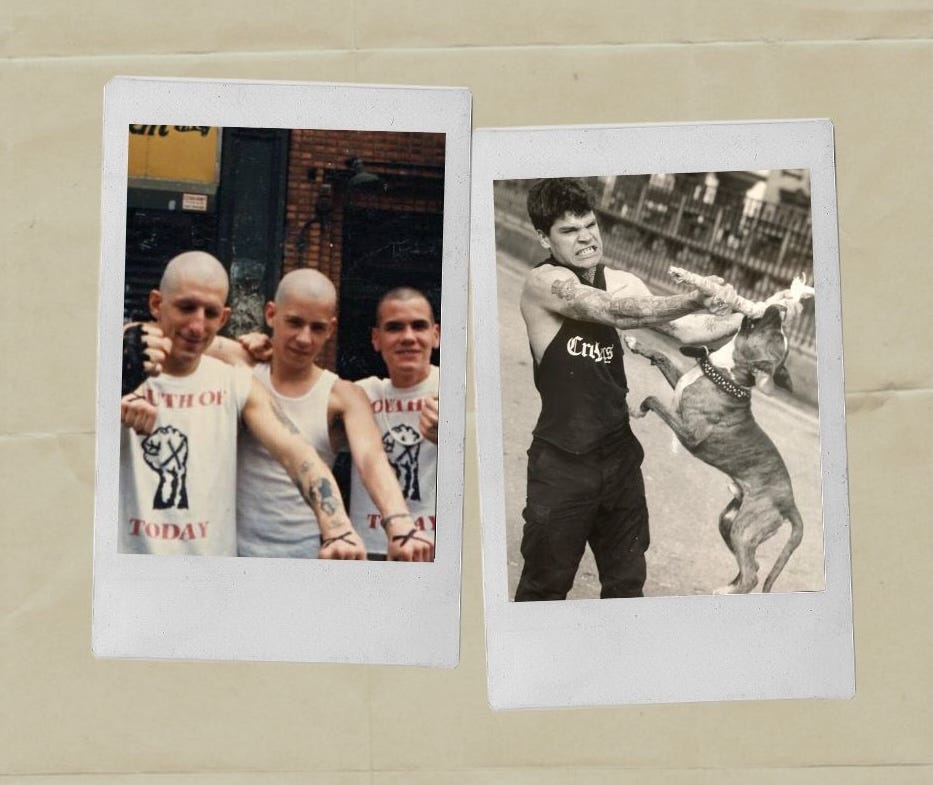

There was a time when being a hardcore kid may have necessitated a certain level of “hardness,” but not for the reasons we’ve somehow carried with us into the 21st century. In New York, specifically, the first wave of hardcore kids all lived in the harshest of neighborhoods because they either grew up there or they genuinely couldn’t afford to live anywhere else. At some point, almost everyone you know from that first wave of New York hardcore rested their heads in abandoned buildings like C Squat (at 155 Avenue C) or illegal basement dwellings like Apartment X (at 188 Norfolk Street)—and Alphabet City and the Lower East Side in the 1980s were quite simply no joke. Those of us who grew up in the city were frequently subjected to sharing what’s been called the Alphabet City Nursery Rhyme with out-of-towners: “Avenue A, you’re adventurous. Avenue B, you’re brave. Avenue C, you’re crazy. Avenue D, you’re dead.” If you think that sounds hyperbolic, you weren’t there.

Being “soft,” at that time and in that environment, was a liability. And hardcore’s early focus on Lower East Side “crews” and New York “brotherhoods” was a true reflection of their daily focus on collective survival—because no one was going to survive those neighborhoods without collective strength. Occasionally, that toughness spilled over into inter-scene discord and rivalries (the Boston versus New York thing was real), but for the most part, how “hard” you had to be was proportional to how hard your living conditions were. It meant occasionally having to protect yourself against violent drug gangs and actual street criminals. It was not an attitude you cultivated for the purpose of fighting your fellow hardcore kids.

Of course, by the time I showed up in 1987, most of the kids I met were more like me: Fucked up in our own different ways, but more or less stable. No one my age ever lived in a squat; no one I hung out with was truly fighting to survive. And yet every weekend we dutifully showed up to CBGB wearing steel-toed Docs on our feet and scowls on our faces. We were there to have fun, but we also felt a necessity to be on high alert—ready to snap if anyone posed a threat to our self-calculated street credibility. Unlike our predecessors, the majority of people who went to hardcore shows in the late ‘80s no longer needed to prove how “hard” we were in our daily lives, so there was no one left to fight but each other.

I don’t need to tell you this was a fucking disaster on multiple levels. Don’t get me wrong: There were tough kids at the shows who were absolutely genuine. But what’s spoken about less is how so many of us struggled to fit an archetype that we were never meant to wear. Week after week, we struggled with the relentless grind of being youth intent on fitting in, earning respect, and doing what we thought we needed to do to pay our dues.

In 2024, many of these concerns—while not entirely in the rearview mirror—have significantly abated largely alongside the rise of a newer generation of bands who seem intent on presenting hardcore as a more kaleidoscopic way of being, and perhaps none have been more successful in that regard than Turnstile. Unsurprisingly, their propensity to experiment with genre, aesthetic conventions, and “wearing colors,” as singer Brendan Yates jokingly puts it, has also made them polarizing figures in the neverending what-is-hardcore debate. But it’s also true that hardcore’s tough exterior was never meant to render other values, like individualism and authenticity, as less important.

“I think, fortunately for me, after a few years of getting into hardcore, I realized it’s cool to be yourself and you don’t necessarily have to be hard,” Brendan recalls, for a conversation that will be published in full on Thursday. “Because going in at first, the initial black-and-white perception is that [hardcore] is not a place for you to be vulnerable. Even just growing up, before I started going to shows, with skating, there were always friends who would call you a ‘sissy’ as soon as you started talking about your feelings or something. But once I was traveling more, and having groups of friends around me where I realized I didn’t necessarily need to have my guard up, I could be more comfortable. Like, who are you actually trying to present tough for?”

The irony of eventually claiming my own “softcore” was that, somehow, I earned the respect of more “tough guys” than I ever did by throwing a punch. It turns out all they ever wanted was for me to be as weird and as chill as I wanted to be. At some point in the late ‘90s, a friend told me that my name came up in a conversation with Cro-Mags singer John Joseph—someone I literally feared only ten years earlier.

“I love Norm,” John told him. “He’s a bugged-out dude.”

I was so happy with being called a bugged-out dude because being a bugged-out dude felt more like myself than any of the masks I wore in the ‘80s. I felt seen.

III.

Perception is an unreliable thing. When I was a teenage skinhead carrying a hammer in my jacket, I thought I was following in the footsteps of the angry skinheads in my record collection. But the older I got, and the more of my childhood heroes that I met, the more I realized that they were actually just really sweet people.

Roger Miret gave me the first interview I’ve ever done for a fanzine, in 1989, when I was 15. I can’t imagine I was an interesting conversationalist at that age, but I will always remember the patience and encouragement he showed me that day. Similarly, I didn’t meet Raybeez until the ‘90s, but there was no way you could be around him without smiling. Even Harley Flanagan, master of the skinhead snarl, spent an entire day with me in 1997, just telling me story after story; his only objective, it seemed, was to make me laugh. These were not the people I thought they were when I was a kid. Maybe they grew up. Or maybe we never gave them the credit for knowing that “being hard” is not a personality.

That’s not to say there weren’t signs. I always think about that Warzone song, “In the Mirror.” If New York hardcore ever had an emo song, it was this one—and that might be why I immediately gravitated to it when it came out in the summer of 1987. Raybeez was only 26 years old when he wrote it, but that’s how old you were if you were “old school” back then. (For reference, I was thirteen.) As such, he often approached his lyrics with the gravity of a scene elder, and “In the Mirror” is as personal as he ever got. I still feel a tinge of sadness when he sings, “It’s too bad we’ve had to go through so much pain / But that pain, it helped me grow,” but it’s for that same reason that I don’t regret my “tough guy” years. Sometimes, it’s so much easier to know who you are after you’ve spent enough time painfully pretending to be someone you’re not. As Raybeez eventually concludes, “Now I know who I am when I look in that fucking mirror.” That is, in fact, the entire point of the song.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Brendan Yates of Turnstile.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

Really enjoyed reading this, is the toughness a rite of passage for a lot of young men? I grew up in more metal circles and it was the same to a degree, almost encouraged to fight by friends and peers, and yet ultimately it’s so pointless.

Please keep writing, I’ll keep reading.

I didn't grow up in an environment nearly as rough as yours - it was a neighborhood that kids from the suburbs thought was the hood, but people who actually lived there knew where the *real* hood was - but violence was tied up with punk and hardcore nonetheless. I can't remember a single show where I wasn't waiting for something to pop off, whether it was a new guy in town ending up in the hospital for looking at the wrong person the wrong way, ducking out of a show early because the local neo-Nazi (who had it out for me) showed up in the pit, or cops breaking up a show early to shouts of "I smell bacon in here!"

How much of that was a product of our upbringing and environment and how much of it was aggressive music giving tacit permission to be aggressive? I don't know, probably some of both. Violence in the scene (and school) was certainly normalized. And one of the things I really appreciate about your writing is the way it humanizes people who I would have been afraid of too, and who would have probably knocked me out for not being hard enough. Because they're still people.