The Real Thing

If I was really going to create a digital version of a physical fanzine, I only had to remember the feeling of creation—not the memory of touch.

I.

A couple of weeks ago I brought up the story about how my first fanzine came to be. The abbreviated version is simple: It was 1989, and I was failing out of high school, so my guidance counselor suggested I learn a trade at an affiliated school for at-risk students. I chose to take a course in offset printing because I suspected I could use the class to print up free copies of a fanzine that I could sell at shows on the weekends—the proceeds of which I would then use to pay for the shows I was going to. (It was kind of genius coming from a soon-to-be high school dropout, if I don’t say so myself.) The plan ultimately worked, and it was life-changing to the extent that I can still draw a direct line from that year to the present moment. Because I did, in fact, become a writer and publisher. That just wasn’t the trade I signed up for.

Which isn’t to say I didn’t learn anything from lithography. Up until that point, I took for granted that things just existed. I didn’t really take into account, for example, just how many people were necessary to lend their skills, knowledge, and talent to the process before I could hold a seven-inch record in my hand. From the band themselves, to the studio engineers, to the label manager, to the artists and designers, to the pre-press production manager, to the pressing plant, to the distributors, to the shipping agents, and then finally to the record stores—none of it truly occurred to me, and even that breakdown is potentially oversimplifying it. But after taking that course, I realized that producing even a simple ten-page fanzine was a rigorous, multistep process. It took care and it took work.

Desktop publishing wasn’t really a thing in 1989, so I had to learn typesetting. I wrote the text of the fanzine into a massive word processor and then printed that text onto a heavy thermal paper, only to cut that paper up with an X-acto knife and then manually cut and paste the layout onto cardboard spreads. After that, I’d go into a darkroom to create negative film of the layouts, which we would then use to make printing plates. We took the plates to the press and then started the actual printing process, which takes time and close attention, before moving on to binding. Holding something that was “hot off the presses” became a very literal idea to me, and the way I looked at physical objects changed forever.

I remember how it felt the first time I held that zine—in many ways, the first physical artifact of my existence. It gave me a sense of pride, and that pride was validated when people gave me the fifty cents I charged for the fanzines outside of CBGB that summer. But crucially, it felt like I’d done something “real.”

II.

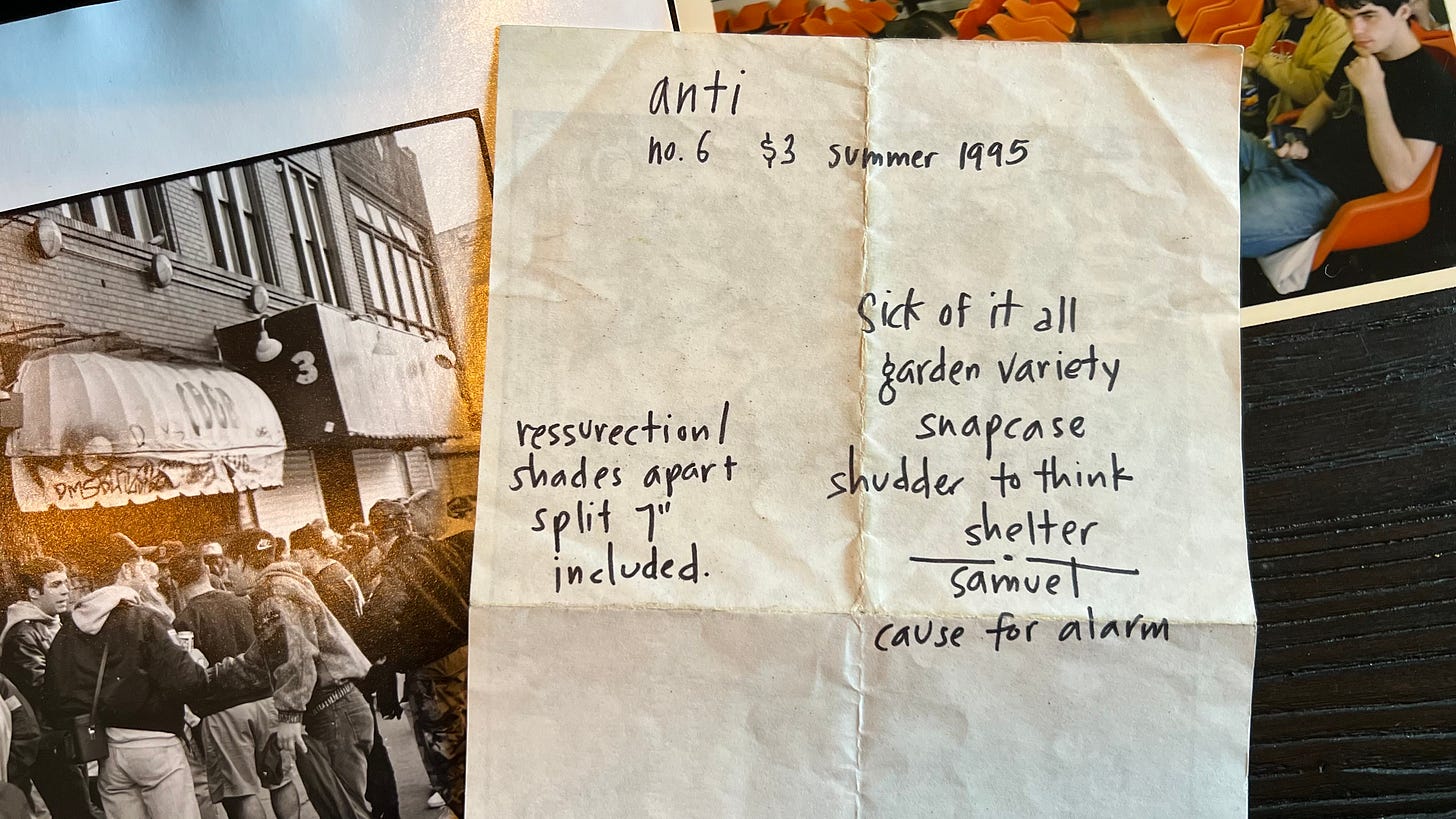

The irony of my trade school experience is that, between the advent of the home computer and the sudden ubiquity of copy-shop chains like Kinko’s, careers in typesetting and lithography went from stable professions to archaic specialty services within my first decade out of high school. When it came time to publish Anti-Matter in 1993, I did choose to go with offset printing—partially as a nod to my past and partially for the “prestige” look of not being photocopied—but knowing what we know now, even if I hadn’t folded the zine in 1995, I’m not sure how much longer it would have been viable. There was a cultural shift happening, and it affected everyone.

By the late ‘90s, services like Blogger and Typepad established a digital model for independent publishing, and the demand for print began its long and steady decline. Soon after, we ushered in the post-Napster millennium with a generation that came of age listening to digital music, free and available on demand. The introduction of the iTunes Music Store in 2003 helped curb the tide—and created a platform that reacquainted users with paying for music, at least for a little while—but it was clear that our entire attitude towards physical media was changing. The hardcore scene was not impervious to it: People literally just stopped doing zines. Labels struggled to leverage illegal downloading into physical sales, and many chose to focus on only one physical format (vinyl or compact disc) as a way to keep from bleeding money in manufacturing for an uncertain future. Many of these labels, unfortunately, still went under, as did Mordam Distribution—the legendary independent distributor responsible for the catalogs of Alternative Tentacles, Lookout!, Jade Tree, and Kill Rock Stars, to name a few—which eventually shuttered in 2009.

Grady Allen, the lead singer for Anxious—whose Little Green House was easily one of the best albums of 2022—is still only in his early twenties, but he’s always struck me as an old soul. In addition to Dying Tradition, a direct mail newsletter that he published to cover his obsessive interest in Connecticut hardcore, Grady is also enough of a well-known record collector to have earned a 2018 profile in No Echo to talk about his collection, when he was only seventeen. When Grady and I sat down for our own conversation, to be published in full on Thursday, I asked him about this “old world” hardcore approach.

“I just think the experience of interacting with [physical objects] feels more substantial,” he explains. “It takes more work to seek out a physical zine or a release. Even if it’s as simple as ordering something or reaching out to somebody on the internet and giving them your address, there are a few more hoops that you have to go through to ultimately receive this thing and interact with it. And on the other side of that, I think when you’re done interacting with this thing, it sticks with you a lot more. It has a larger capacity to resonate with me because I’ve experienced it in a more physical way, and I think it’s so easy now—with your phone always being on—for you to experience something, and then for it to fade completely.”

In the years since Mordam closed in 2009, of course, the hardcore scene has undergone a renewed and sustained interest in physical media, especially among Grady’s generation. For those who grew up reading Pitchfork as their “zine” or curating record collections in Spotify, however, the idea of holding something in their own hands is sometimes an end in and of itself; mere physical ownership is the experience. This somehow accounts for the impossibly odd statistic that 50 percent of people who purchase vinyl records don’t actually own a turntable, but it also raises a bizarre question: Is holding a record you don’t listen to more “real” than listening to a record you can’t touch?

III.

Truthfully, I never wanted Anti-Matter to be a website. I certainly never wanted it to be a podcast. My experience in making physical media—zines, books, and records—has made it so that I have always chased the experience of holding a warm object in my hands; I have always chased the feeling of removing the shrinkwrap or opening to the first page. Most of my favorite things come with physical memories. Like the first time I came home with the New York City Hardcore: The Way It Is compilation and how I carefully inspected every page of the album-sized lyric booklet. I’ve sold a lot of my record collection over the years, but I still have that original first pressing for no other reason than the strength of that memory.

Even when I decided to make Anti-Matter a subscription-based “newsletter,” for lack of a better term, I was thinking tangibly. A website is a place that you visit, but it’s not necessarily a journey or a destination. None of my fondest memories come from clicking on a bookmark. But there’s something intimate about inviting me into your inbox twice a week, and there’s something that feels very real to me about waking up to a new email that is asking for you to act—to open it, to read it, to engage with it, or even to put it aside, purposefully. Since launching in July, I’ve seen so many posts on social media where people have talked about reading Anti-Matter as a morning ritual, and that makes me feel like I am doing something right—because so much of experiencing something, for me, is the sensuality and the ritual. That makes me feel like this, too, is “real.”

That said, I also knew fully well that crafting a digital experience would come with its own hurdles. Because in addition to our skewed relation to physical artifacts, we also still carry a skewed perception of digital ones rooted in those early 2000s struggles—questions of credibility and value and “realness” that, quite frankly, I never felt when Anti-Matter was a print publication. I also never felt as fraught about the finances of doing Anti-Matter when there was a physical magazine involved; there was never a time when I became self-conscious about asking for the three dollar cover price. With this iteration, though, I’ve realized that I can still be actually quite shy about asking you to consider a paid subscription—despite the fact that I’ve quite possibly never worked so hard on anything else in my life. I’m working on that, too.

But maybe that’s the thing. Publishing this version of Anti-Matter has given me the same kind of insight into digital media that learning lithography and typesetting gave me for physical media in 1989. Up until recently, I probably treated the internet like it just existed. But now I understand that if we really want to make something that’s worth spending our time with, it takes care and it takes work—whether we can touch it or not.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Grady Allen of Anxious.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

Print zines are coming back in an interesting way, partly because of the accelerated decay of digital spaces and the aggressive censorship of our existing ones. I'm really excited to get to go to shows and trade zines with people but it's bitter sweet that it's partially in the wake of the instability of something as ubiquitous as the internet.

Regardless, I think the amount of work that goes into current anti matter really shines through in its care and insight. Thanks so much for it, its become a fixture of my morning commute.

I think the recent vinyl boom is in connection with (as opposed to in opposition to) almost all music being available for (essentially) free digitally. I am well aware that I can listen to (insert LP I recently mail-ordered here) on Spotify, and I do that most often, but because the artists receive very little in the way of compensation for those digital streams I want to show my support by also buying (and listening to when I have a moment to myself) the physical copy. I've been buying physical records for over 20 years at this point, but, to me, it means a bit more to do it these days.