Life of a Spectator

When history is recorded, we'll hear a lot about our scene from the bands and the zine editors and the label owners. But will the kids have their say?

I.

For the first few years of my involvement with hardcore, I did not attempt to start a band, or make a zine, or book a show, or put out a 7-inch, or do anything that would make anyone call me a “contributing member” of the scene. I went to school during the week, I listened to Crucial Chaos on WNYU every Thursday night, and I went to Bleecker Bob’s to buy records when I could. Other than that, I “just” went to shows. A thirteen-year-old kid only has so much time and money, and that was how and where I chose to spend it.

It was a mostly uncelebrated life, but it was fulfilling. Going to shows was how I made friends. Expressing myself in the pit was how I felt connected to my body. Studying album lyrics and liner notes was how I educated myself on the principles and traditions of the scene. I was well aware of the do-it-yourself ethos—I knew about Dischord and sang along to that Gorilla Biscuits song in 1987—but I also didn’t feel any pressure to make something just for the sake of making it. To use today’s parlance, being a “creator” may have increased your visibility in the hardcore scene, but it wasn’t necessarily something that determined your worth. There were plenty of kids in the scene back then who you’ve never heard of that are still like stars to me. Just being there was enough.

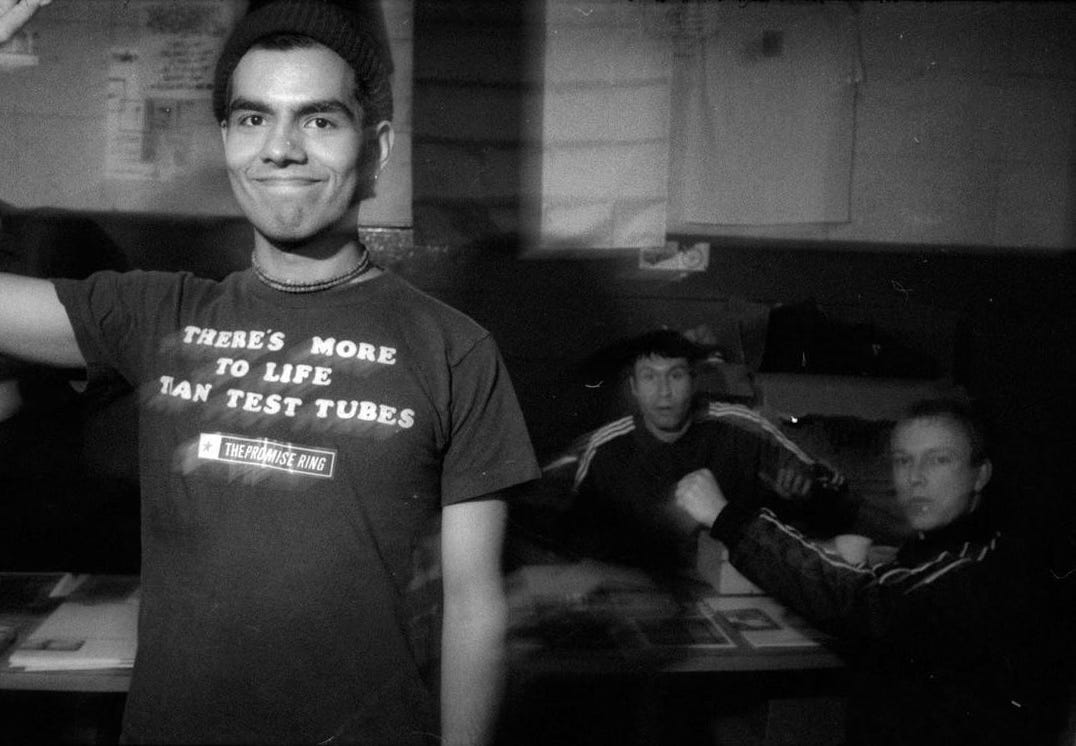

I crossed the rubicon into “contributing member” status in 1989, when after being told I was in danger of failing out of high school, a guidance counselor suggested I consider enrolling in a vocational program that would both count towards my diploma and take me out of regular classes for half a day, three days a week. These programs were designed to teach at-risk students a practical trade; the assumption being that I was simply not college material. At that point in my life, to be fair, I was not. But that didn’t mean I couldn’t be an enterprising young man: After looking at the catalog, I signed up for a lithography course—a printing class, essentially—and before I’d even stepped foot in the classroom, I knew that I would use this course to write and publish my first-ever fanzine for free, and that’s exactly what I did. In the end, I completed the program with high marks and 500 copies of a ten-page zine that featured interviews with Roger Miret from Agnostic Front and Mark McKay from Slapshot. I made 100 dollars selling them outside of CBGB that summer, and just like that, without even realizing it, my “spectator” era ended.

II.

A couple of months ago, while doing an interview with Ed Macfarlane of Friendly Fires, I was confronted with an idea that I’d never considered. When I asked if he’d ever identified as a hardcore kid, Ed very firmly argued that he never earned the right—if there is one—because he had only ever “just” gone to shows.

“If we’re talking about being within a community of people working in a scene and doing things together in a scene,” he explained, “then no, I’ve never ‘been hardcore.’ I’ve always been someone on the outside looking in.”

In other words, Ed legitimately felt that his membership in the hardcore scene was contingent on doing more than just going to shows. More than that, it also seemed to include something that looks like “work.” To be honest, this assessment made me sad. It made me wonder how many other kids felt marginalized by their own community—“on the outside looking in”—because our emphasis on “doing something” is somehow inadvertently promoting the idea that going to shows is not enough.

I was reminded of this exchange during my recent conversation with Koyo’s Joey Chiaramonte—the full version of which will be published on Thursday. In this rendering, though, Joey recalls his formative years in the Long Island hardcore scene—before he worked as a tour manager for Vein.fm, and long before Koyo got together—as a period of participation devoted only to going to shows. By his account, the very thing that Ed felt disqualified him from “being hardcore” is the same thing that Joey felt empowered him.

“In so many ways, the culture is about getting back what you give,” he told me, “and what I gave was true, genuine, passionate attendance that had no regard for the social component. It was like, I don’t care if anybody knows me, likes me, or wants to be my friend. I just want to be here and see these bands that I’ve become obsessed with. I gave passionate, unwavering attendance, and [through that] I gained the acceptance of my peers, and then made many standing friendships that have spanned a decade long now… But on a baseline level, the only real requirement to genuinely participate with this culture is to just be there and literally get through the door.”

Thinking back to my own “spectator years,” I have a deep appreciation for the kind of endearing purity attached to my existence in the scene at that time. Much like Joey, I went to shows with no other objective than to support the scene I loved. I provided financial support by paying at the door or buying a t-shirt. I provided community support by being a dependable number that venues could count on when they needed to decide whether or not to continue booking hardcore shows. And I provided moral support by singing along and stage-diving and letting the bands know their work was loved and appreciated. Not only that, but I did it all without expecting anything in return—including acknowledgement. Which is, perhaps, part of a problem: If we accept the reality that it would be completely impossible to sustain a scene in which everyone has a band or a zine or a club or a record label, then why is it that we reserve so much of our adulation for hardcore’s creative class? What might it look like to lift and acknowledge the role of those people who “just” go to shows, without whom, we’d be left with nothing?

III.

Over the last several years, we’ve seen multiple attempts to chronicle the history and impact of hardcore and its many branches through books and film. Even The Anti-Matter Anthology, in 2007, took a stab at trying to create a varied, but cohesive document of the ever-evolving landscape of 1990s post-punk and hardcore. But throughout most of them—all of them?—is the conspicuous absence of anyone who “just” went to shows, the actual lifeblood of our scene.

What I know now is that my experience is a skewed one. Almost everyone I know is a “contributing member” of some sort—whether they play in bands, write for websites, take photos, book shows, put out records, manage bands, design records and merchandise, or work in the touring industry—and it’s been that way since 1992, if I’m being honest. So while I am certainly qualified to speak about hardcore history, current trends, the general business of “being hardcore,” and the experiences I’ve had as a “creator,” being able to give you an accurate impression of how this work is being truly received by the people who “just” go to shows is something I am not equipped to do. This must be accounted for when we think about how hardcore’s history is being recorded. For example, even though every single hardcore or punk documentary I’ve ever seen eventually makes the hackneyed point that hardcore “makes no distinction between the band and the audience,” every single one of them goes on to make that distinction by speaking only to band members. But some of the most visceral memories I have are from my “spectator” era, when my experience wasn’t yet colored by inside baseball or interpersonal relationships. These kinds of perspectives must not be erased.

Perhaps we need to rethink the ways in which some types of participation are emphasized over others, and how the fetishization of DIY culture—although certainly well-intentioned—also comes with a set of exclusionary blindspots. For one thing, not everyone has a skillset that works with the needs of the community at any given time, and we should always encourage each other to work with our strengths. (Relatedly, how many record labels have been started by people who had no business working with accounting? Let’s just leave that there.) It’s true, too, that some people come to hardcore as an escape from their everyday lives, and that they see going to shows as a place to get away from work, not to make more—and that’s OK, too.

Less obviously, though, it’s also worth considering that being a DIY “creator” is sometimes made possible by privilege. It often means we have the time or the money or the luxury to fail, and the reality is that for many of our most struggling community members, these things may not be accessible. People have jobs or families or debt or schoolwork or even housing and food insecurity. Sometimes, “just” going to shows is literally the absolute most that one can do—and no one should ever feel less-than for that. No one should ever feel like that’s not enough. Because I do believe that, ultimately, “being hardcore” is about being here, passionately and unwaveringly. At its core, it’s about contributing yourself. That will always be enough.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Joey Chiaramonte of Koyo.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

Hardcore fundamentally isn’t a room full of well-adjusted kids who have strong internal senses of self worth. 🤷♂️

When I found punk I found where I felt like I should be, but that doesn’t mean I felt like I belonged. That feeling was common for me regardless of being in a band, making a zine, putting out a record because it was something broken INTERNALLY that kept me feeling inadequate. I think that feeling is probably common among people who played in bands, did zines, put on shows, released records, or just showed up. We end up in hardcore because we don’t feel accepted/belonging/connection elsewhere.

See also: True Hardcore (II) by Fiddlehead and the conversation you and Pat had about it.

This was so particularly well-timed at this point in my life. I’m an artist in a different field and much of my involvement in the hardcore scene is to enthusiastically support artists who are doing their best to be honest. It’s my break from the way that vulnerability asks a lot of me in my own work and a recognition that other kinds of artists are being deeply vulnerable too. Shows are a comfort. Thanks for writing this (the zine in general and also this specific post).