In Conversation: Tim Kasher of Cursive

He has spent his entire adult life playing in Cursive. Now, only a few weeks after his 50th birthday, Tim Kasher is intent on finding that elusive balance between hope and fear.

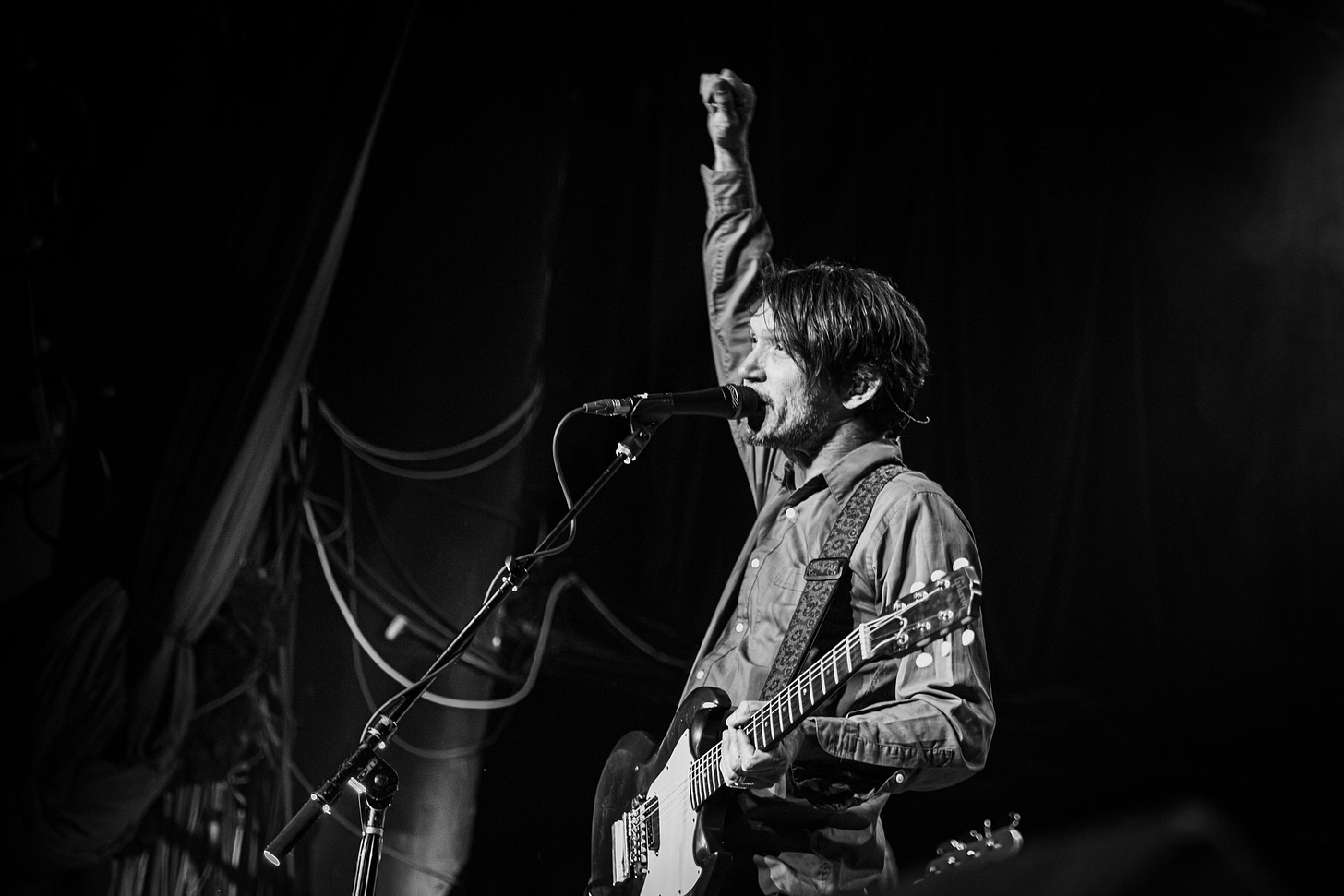

After nearly thirty years as a band, Cursive have cemented a reputation for being one of the most consistent and consistently unpredictable bands to have ever grown out of the mid-’90s post-hardcore boom. But even with the release of Devourer, their bold and excellent tenth album due this week on Run For Cover, singer/guitarist Tim Kasher is still bracing himself. After years of geographical isolation and near-constant rejection, the inhibitions Kasher developed as a member of Slowdown Virginia—his jaunty and angular pre-Cursive, post-punk, and (arguably) proto-screamo band—still run deep. He takes nothing for granted.

My favorite conversations have an arc—a point where the entire discussion shifts into something neither of us prepared for—and that’s exactly what happened here. In this case, a chat about growing up in the insular early-’90s Omaha scene as a “debilitatingly humble” kid unexpectedly opens itself up into an exchange that skews much closer to Kasher’s lyrical id. Not unlike many of the songs on Devourer, we become increasingly preoccupied with questions of aging, mortality, fiscal security, and social insecurity—topics that, I realize later, have become more and more prevalent in the broader hardcore consciousness in recent years.

“I want so badly to leave something here that’s a part of me, that is me, for after I’m gone,” Kasher tells me. In other words, his drive to create walks hand-in-hand with his drive to exist.

As far as I know, you might be the first person I have ever interviewed who came into this through a cover band.

TIM: Oh, really?

I mean, I’m sure people have all sorts of things buried in their closets, but your story is more of a well-known fact. So that’s interesting to me because even though most of us learn how to play music by learning other people’s songs, it feels like, for you, playing in a cover band was actually just the most viable route to start making music in early-‘90s Omaha.

TIM: Absolutely. But this was also when I was fourteen or fifteen years old, somewhere in there. The only examples we had were a few older high school bands, who would play at the proms and homecomings and bonfires. They had some original music, but it was mostly covers. That was the only route we saw. So we just thought, “Well, if we learn a slew of covers, then maybe we can get a show!” We actually started writing originals pretty quickly, though. Initially, I remember my songwriting was more kind of… cute [laughs]. But we continued to play covers because we recognized the fact that those covers could get us paying gigs from the high schools. And then we would take that money to the studio to record our own songs.

You weren’t the singer, but you became the singer when that band [the March Hares] eventually morphed into Slowdown Virginia. Did you always think of yourself as a singer?

TIM: I think that, for me, there was a lot of Midwestern attitude and ethic about what I was doing. In my head, I had visions of writing records and the daydream of being some kind of big writer. But to be “a lead singer,” that felt too cocky, too egotistical, to be the guy who was like, “Get out of the way! Point the spotlight on me! Get me my hero box”—or whatever you call it. That just wasn’t me. At the same time, I was already writing all the lyrics for our originals and giving them to our singer. It felt like I was already on the path. So maybe it was just me getting a little bit older and thinking that maybe my voice was OK to sing. I mean, my voice has been a tricky thing my whole life, really, but back then I definitely didn’t feel like it was appropriate to be a singer. But as you know, it works in punk rock. And at that time we were starting to be introduced to the actual music scene in Omaha around us, which helped me recognize that you don’t necessarily have to be “a good singer,” you just have to sing and express your ideas.

How would you describe what was happening in the Omaha scene at that time?

TIM: I’ve always thought about it—and I always tend to speak about it—as pretty small. It was pretty insular, and there weren’t a lot of rivulets or genres or different scenes. And so I’ll describe it as such, because we were basically introduced to the broader punk rock scene at that time—and, as we know, that’s a wide umbrella. Like, under that punk rock scene there was also “weird folk” [laughs]. There was all kinds of stuff, but it was DIY and it was the punk scene, you know? But that definitely wasn’t all it was. There was definitely a metal scene, and as I got older, I started to recognize something like a more specifically pop-punk scene, and there started to be a lot of crossover as far as who you knew, but maybe less so as far as who you played with. So even though it was small in Omaha, there was still some segregating going on.

Where did one find punk culture in Omaha in the early ‘90s?

TIM: I think the Antiquarian has gotta be the absolute right answer for that. It was the independent record store in downtown Omaha. There was this guy Dave Sink, who was a pretty legendary figure in the Omaha music scene, who ran this store in the basement of the Antiquarian bookshop. There were other record stores, but that was the “cool” one, you know? You’d go in and he would talk to you and he would kind of shit on your tastes, but then he’d help point you in the direction of what you should probably be listening to. He gave us all so much good advice and so much good music to listen to. That’s, like, the record store owner’s job, or at least it could be your job—and in Omaha, we needed that job. We needed someone to take on that mantle of scouring the music at large and showing it to all of us.

I went back and listened to the Slowdown Virginia record this week and it was interesting to me because, hearing it now, I don’t think it’s that far off from some of the other things that were happening during that first Anti-Matter era, from 1993 to 1996. It wasn’t ridiculously far out from a band like Angel Hair or even Current. It felt like the only thing that really separated you from all that was geography.

TIM: It was tough. It very much felt like we were on an island. For the years that Slowdown was happening, we just weren’t tapped into the larger scene. Like, you mentioned Angel Hair. I probably didn’t really know Angel Hair until I picked up one of their 7-inches in the late ‘90s or something. Being from Omaha, I just think that I never expected that anyone would really hear our band. It felt very much like something we concocted privately in our basement for a really niche group of people.

Did that ever feel demoralizing?

TIM: It was definitely frustrating! Because we were certainly doing whatever all the other bands were doing around the country. We had a copy of Book Your Own Fuckin’ Life. We were sending our music to labels and stuff like that. It's tough when you’re just taking constant rejection. But I don’t know if it’s any more or less frustrating than anyone else who is in a band and trying to get someone to pay attention to you, someone to notice what you’re doing.

You said in another interview that you grew up with, quote, “a debilitating humility” [laughs]. And that phrase really stood out for me. Because I was trying to figure out: When you have a debilitating humility, how do you even get your foot out the door? How does a band like Cursive even happen?

TIM: Slowdown Virginia had just exhausted itself, I would say. There was a turning point in our lives where high school was done and college was starting, and there was this sense that we had to start taking life a little more seriously here—and Slowdown Virginia was not feeling very serious, nor was it working. So I ended it with that attitude: Hey, that was fun, we’re friends, we gave something a try, but it didn’t matter. It wasn’t gonna matter. Nothing was really gonna come from it and that’s fine. But [future Cursive members] Steven Pedersen and Matt Maginn came up to me one afternoon, and they were like, “We don’t understand. If you’re still going to be around for school, I don’t know why we have to quit playing music.” They were basically wondering why I needed to have this staunch finality to it, and I gave that a lot of thought.

So that’s all my big preface for saying that the attitude I had when I started Cursive was probably the adverse of debilitating humility, because it was really one of the decisions in my life where I was like, “OK. Fuck it. Let’s go for it.” And for me, that meant, if we’re going to do it, then let’s actually do it. Like, what if I gave it a real shot? The M.O. for Cursive was that I never wanted to release anything that you think you might be ashamed of in the years to come. That was me trying to level up.

Which is to say that you weren’t really debilitated anymore, because on some level, that actually sounds ambitious. Especially the idea that you don’t want to put anything out that you might regret—that requires some self-awareness that a lot of college-aged kids might not have.

TIM: That’s a great way to put it. That’s such a huge part of it what it was because there was just no self-awareness in Slowdown Virginia. The music was fun—and there’s nothing wrong with fun music—but I was trying to write the best music I could and none of it was being taken seriously.

OK then, I want to challenge you to answer this question in the least humbly way possible.

TIM: [Laughs] All right!

When things actually start happening for Cursive in a bigger way—when The Ugly Organ is selling almost 200,000 copies, or later when you’re playing on David Letterman and seeing yourself on TV—is there a moment where you get caught up in dreaming a little bigger?

TIM: I think the best way for me to answer this is by saying that I experienced all of that after the fact. Especially during Ugly Organ, when everything was happening all the time for us, and we just kept touring and touring because we kept being invited to more stuff. It was all pretty cool. But the reason why it never got to my head is because everything was really relative. There was just a really unique growth happening at that time in our scene because Bright Eyes was also doing it and The Faint were also doing it. Bright Eyes were doing it a lot bigger than we were, and I felt The Faint were kind of bigger than us as well. So I say I didn’t know until after the fact because it wasn’t until a decade later that I would look back and be like, “Oh man. You fit through that pinhole of ‘success.’ That’s so hard to do, and you didn’t even realize what a huge deal that was because Bright Eyes and The Faint had already done it and it just seemed so natural.” Like, I would be so fucking gobsmacked if I ended up on some kind of year-end list for an album I put out now. But it’s so strange to me, and so surreal, that I wasn’t gobsmacked then. It didn’t seem like we were unique or special or anything; it just seemed like we were following a path that was already being carved out. I kind of regret [missing] that.

It’s funny you say that because I tend to think more about the way Ugly Organ somehow also happened in the middle of the early 2000s “emo explosion.” That feels like a more enduring memory for me. And I would assume being swept up in that came with a little baggage as well.

TIM: I’ve never thought about that before, and it’s fascinating because you’re right. We did accidentally end up being part of the zeitgeist of that scene. I just haven’t thought about it in those terms. But also this probably goes back to that crummy attitude I tend to have of feeling like we are outliers, that we don’t really fit in well with scenes or whatever.

Every time you bring up that “crummy attitude” it sounds more and more like a defense mechanism.

TIM: Yeah. I mean, this is all fun stuff to think about. One thing is that when we started Cursive, we wanted to be “genre-less.” But if you go back to those first three records, I can look back and be like, “Oh. You’re kind of in a genre.” I love those records—I’m not ashamed of anything we’ve put out!—but I do listen back to them and think that we kind of got a little cozy in something that I guess you can call “post-hardcore.” So Ugly Organ was me wanting to break out of that. To me, it sounds more like Slowdown Virginia in the way of being that writer who feels like he’s living on an island and doesn’t know what to take influence from.

While we still kind of want to be outliers because we don’t want to fit too snugly, it’s also a Catch-22 because you still want genres to accept you so you can play their festivals [laughs]. It just goes back to my own psychosis of going to a party, and then leaving that party, and immediately thinking, “Wow. Everyone really hated me there, didn’t they?”

It reeks of, “You can’t fire me, I quit!”

TIM: Totally! It’s just leaving a party and saying, “I don’t think anyone liked me, but guess what? I don’t like them either!”—as you wipe the tears away [laughs].

So that’s not humility. That’s insecurity. Where does that come from?

TIM: I want to just lean on Nebraska again for that, but maybe that’s just too pat, you know? It’s paranoia, it’s insecurity. It feels like I’m fucking going through it all the time—or at least I am right now because I have new record coming out and I’m working on a movie and it feels like, “Oh God, I’m about to get dumped on so hard by the world.”

I feel like I have to play the psychologist and say, “How do you think this connects to your family?” [laughs]

TIM: I mean, I am the youngest of six and I know for certain that certain issues come out from the way I was raised. I was raised in a good family, but it was a family that had already moved on by the time I was born. The children started raising themselves. So I became fiercely independent. As far as things my parents accidentally gave me, I do appreciate how independent I am.

But you’re helping me put this all together, so how about this? At the core of my being, I just wanna be liked so badly. And I think that you have to set up these insecurities as walls that you put up. Because this process of putting out these creations that you’re responsible for making, and then being subjected to people’s opinions about them… I have to put up some kind of wall to brace myself because I get really down about it. I do. It’s just a thing that I have, needing to be liked. But I learned something from the musical Chicago, which I really love, when Roxie has a song and she goes into this little speech about how she ended up on stage because she wasn’t loved as a child. She was on stage seeking out everyone’s attention and seeking out everyone’s affirmation. I was like, Oh. Yep. I get it.

The new record starts out with this kind of existential moment, where you say: “This is the end of your life / It’s shocking how long you fought to survive / Botch job, you fumbled the ball / Never quite got self-actualized.” That’s a pretty disaffected way to begin.

TIM: I mean, I know why I’m writing those things. This is kind of like a panic mode for the age that we’ve become. Sure, if I can make it to 70, I will look back to 2024 and I’m sure my attitude will be like, “Oh man, there was so much life left.” There is so much life left. I can’t believe I’m worrying so much about it. But the thing is that right now, at 50, I can look back to 30 and I know I had those same concerns. It’s just that the anxiety of it is so much stronger now. It feels like it gets more intense with every decade. Some of that anxiety is just, you know, if a doctor were to tell me, “Sorry, you have two more weeks,” I don’t think I could look around and think, “OK! It was a good run. I did my thing.” I don’t think I could feel that way if I made it to 90. I mean, I don’t know what 90-year-old me would be like, but I have a hunch that things aren’t going to change that much for me at this point as far as my inner-self is concerned. And that fills me with a kind of panic and a certain dread. Because I love life. I love it pretty intensely. I want to be alive and I don’t want to die, but my body is already sending me signals [laughs]. It’s sending me signals that I can’t do what I used to do, that things aren’t the same, that I’m on a downward trajectory, and that’s scary. It’s scary for me to think about and feel that way. That’s why I write about it. I want to get it out of my head and onto paper. I want to share it with other people and hope it strikes a chord. It’s my little contribution to all of this—to say I’m having kind of a hard time with this and letting people know that. Maybe we can all feel a little solace in that.

Have you ever had a near-death experience?

TIM: I’ve actually been the unfortunate recipient of a few of them, I suppose. Yeah.

OK, I ask because I remember when I got hit by a tow truck, and I woke up after three days of being unconscious, I had this thought that if everything had ended right there, I would have been OK with that. I had a good life. And that was 20 years ago. There’s obviously so much that I’ve done in the last 20 years that I’m psyched to have done, but it’s interesting to me that you’re saying the opposite. You’re saying, “No, no, I’m actually not done at all” [laughs]. What exactly was your experience?

TIM: Well, the first thing that happened to me was that I accidentally hung myself when I was a teenager. It’s all pretty cloudy, but Matt Maginn was in the room at the time, and I was kind of joking around with a blinds cord. And then, you know, I wrapped it around my neck and passed out and fell off the chair. Matt heard me scraping the wall and he was able to come over and pick me up, and thankfully, there were some scissors there and he was able to cut me free. My entire face exploded. It was pretty dark. Every capillary or whatever just blew up. I had to start my freshman year of high school a few weeks later with this Frankenstein scar and a purple face. That’s how everyone met me in high school. Oh, and also one side of my head was shaved because I cut my own hair and I was a little punk [laughs]. But that experience, at that age, was very sobering.

I think the bigger experience for me, though, as far as stuff that really stayed with me, was that my lung has collapsed a couple of times in my life. The first time was in high school. They couldn’t figure it out. But I have a unique disorder with my lungs. For a lot of people, when their lungs collapse, you’ll go to the hospital and they’ll keep an eye on you and your lung will start to heal—like a scratch on your arm or something. It starts to repair itself. That’s the miracle of our bodies; they can heal themselves. My lungs won’t do that. They will just collapse. I seem to be past it now, thankfully. But back then, they would get big blisters on them, and then they would pop and deflate and they wouldn’t be able to heal themselves. That time in high school, I was in the hospital for seventeen days, I believe. And I was there for so long because the doctors kept trying all these different approaches to get my lungs to mend themselves. It became this question mark for them.

I had a lot of time to just sit around and think. It was a weird time for me and my family because I ended up being this unusual anomaly in the hospital and they couldn’t heal me. That’s when mortality starts rearing its head and no one wants to talk about it. We’d say, “What are the next steps?” And the doctors had to keep shrugging, like, “Well, we’re not really sure.” I still don’t know how that has affected me as a being, but it sure as hell did something to me because it was just strange. It was a time in my life where I had to lay helpless while everyone was buzzing around me, trying to fix me, and nobody could.

In the original iteration of Anti-Matter I did an interview with Craig Wedren [of Shudder to Think] where he told me his girlfriend gave him a copy of The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker, and basically said, “This is you.” The idea was that creative people use their work as a surrogate for immortality. You, for one, are wildly prolific.

TIM: All that stuff makes so much sense to me. Although I’ve never been able to connect the dots of people feeling like they want to have a kid because it’s creating something that is…

…Legacy.

TIM: Yeah, legacy. That “little me.” At the same time, I think that’s a totally natural and healthy attitude that’s probably important for procreation and the continued creation of things. Even in our enlightened heads, that’s becoming baked in: I just want something to carry my legacy, so that when I’m gone, I’ll still be here. But while that never made sense to me, art has 100 percent made sense to me. It has always made sense to me. I want so badly to leave something here that’s a part of me, that is me, for after I’m gone. That feels so innate to who I am.

I’m curious how you think about legacy in terms of your band, because at this point, Cursive has been going for almost 30 years. I can’t imagine you could have ever conceived that it would be going this long. Have you ever revisited earlier versions of yourself in the music and maybe even wanted to correct yourself?

TIM: I mean, I’m never hard on myself. We’re all just trying to express ourselves, so I wouldn’t condemn myself for that. But I do look back and I feel kind of bad for how miserable I actually was—the growing pains, being young and in your twenties, and also medicating with drugs and alcohol like crazy, and how much that was making everything worse. It feels almost laughable looking back at all my relationship problems back then [laughs]. I feel bad for myself and all the others who were subjected to it, but I was just trying to figure stuff out. I feel bad for that little guy who was beating himself up pretty harshly.

OK, but going back to “Botch Job,” that feels like it’s about that point that comes in every musician’s life when we start to think maybe we botched our lives up with this. And even the sequence of the record, going from that to “Up And Away,” which is basically saying, “I thought my life would look differently right now. I must be delusional”… Or am I just projecting my own feelings onto you? [laughs]

TIM: No! I think you and I have shared experiences, don’t you think? I mean, we have literal shared experiences, but also in our upbringings and our livelihoods in music. But with “Botch Job,” I can break those into two ideas. Some of the lyricism in there is kind of referencing a lifelong struggle with chasing inebriation. Whether that be through marijuana lately, or alcohol, and always just needing that escape through inebriation, or finding that sobriety isn’t working well enough for me. It’s about wanting something more, wanting to chase that. But the other prong of that song is that success is relative. I feel so lucky and so successful in the career that I’ve had, while also not being incredibly successful fiscally. In my family, I am the “most successful” because I got to fit through that pinhole and do exactly what I want to do with my life, but I’m also the only one who’s living in a cramped apartment [laughs].

Right. I was actually just talking to someone this morning who is not involved in music and trying to explain how I feel really blessed to be 50 years old and to be still doing this, and at the same time, knowing that even though people might think I’m “successful” by external measures, it is still an absolute reality that I have to constantly generate income to survive or none of this works.

TIM: Absolutely.

And I think even in the hardcore scene, a lot of artists don’t want to talk about it. They want people to believe they’re killing it. But I’m out here like, “If I don’t get enough paid subscribers, this thing is going to die” [laughs]. That’s just being real.

TIM: You’re probably familiar with this conversation—how often over the years I’ll have a conversation with someone I just met after a show and they’ll be like, “It was so cool to see you in this venue! I didn’t think I’d ever see you [at a place this small]!” And depending on my mood, sometimes I’ll just let them live in that bubble; I won’t say anything to refute it. Because if that’s their dream, if they want to think of us as something greater than we actually are, then maybe that’s fine. It’s not hurting anything. Maybe they prefer thinking of their Cursive as mightier than we are.

OK, I wanted to end by bringing up something I noticed on the new record. You have three distinct lyrics on this record that all present a very different version of “what life is.” You’ve got: “Life is like a bowl of grapes / Stomped on until bitter wine is made.” You’ve got: “Life’s an abscess or apple pie / So shut those demons up / And devour your slice.” And then you’ve got: “Life is but a test / Does no one ever get the answers right?”

TIM: Wow. It’s funny that for as much as I pored over this record, I swear I did not realize that I gave three different life adages. On one record, you’d think one would suffice!

Which one do you think is truest to your state of mind right now?

TIM: I can immediately take out the “Bloodbather” one, which is the “abscess or apple pie” one, because that song is a companion to “Botch Job” in terms of songs that continue to grapple with my daily dealings of dragon-chasing and wanting to escape the world for a little while. So that’s in character—and by “in character” I mean that’s the drunk-me saying, “Life’s an abscess, it fucking sucks, so just fucking take a shot!” [laughs] I definitely want to go with the first one, but let me think about the one from “The Loss” because that one feels so devastatingly sad and upsetting. And though it does come from a place inside me, it’s about the darker and more difficult things that we’re all trying to get through.

So the “Dead End Days” one is the one that I would choose. “Dead End Days” is a decent snapshot of how [my wife] Gwynedd and I feel out here in L.A. right now. We like it here, but we feel like they won’t grant us true admission to live here because it’s so expensive and the cost of living just keeps rising. Also, it’s not as grim as “The Loss.” Saying “life is like a bowl of grapes, stomped on until bitter wine is made” is a good adage for me, and for my life in general, I think. I feel like life can offer you a lot of potential in what you can do, but even when all that potential erodes away and gets stomped on, then alas, you can still have some wine [laughs].

It is, perhaps, strangely the most hopeful of the three.

TIM: I have tons of hope. I mean, I have my grounded reality, which is a lot of what we’ve gone over in this conversation. I have all of my built-in insecurity defenses, like not expecting anything from Devourer, and not expecting anything from this new movie, and not expecting anything from the next things that I do—whatever they may be. But what I love about all of this really is that there’s truly no ceiling to the arts, there’s no ceiling to the things we do, because anything really could take off. And even though you mostly know that’s not gonna be the case, it’s still so fun, and there’s always an opening. So for me, what I mostly hope will happen is that whatever it is that I’m currently working on will afford me the next one.

As far as my life goes, I’m still kind of hoping for a long life, but I’ll have to accept that you have to die, I suppose. It’s kind of shitty that, at the end of it, you know you have to die.

Anti-Matter is an ad-free, anti-algorithm, completely reader-supported publication—personally crafted and delivered with care. If you’ve valued reading this and you want to ensure its survival, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Really fantastic interview. I loved The Ugly Organ when it came out, and I remember enjoying Happy Hollow, but I didn't keep up with Cursive after that, for no good reason. I checked out "Botch Job" thanks to the link in this article and I was floored by it. Really looking forward to checking out the new album when it gets released.

I loved the discussion that came about after you mentioned "The Denial of Death". I have absolutely had conversations over the years about how the creation of art and music is the closest thing we have to immortality. It's definitely been a motivating factor for me in recording and releasing music.

Our creations will love on long after we're gone. That's even more true now in the age where almost all of recorded music is available digitally and more of us fancy ourselves as archivists and revive long lost recordings and printed material through electronic formats that are easily distributed far and wide.