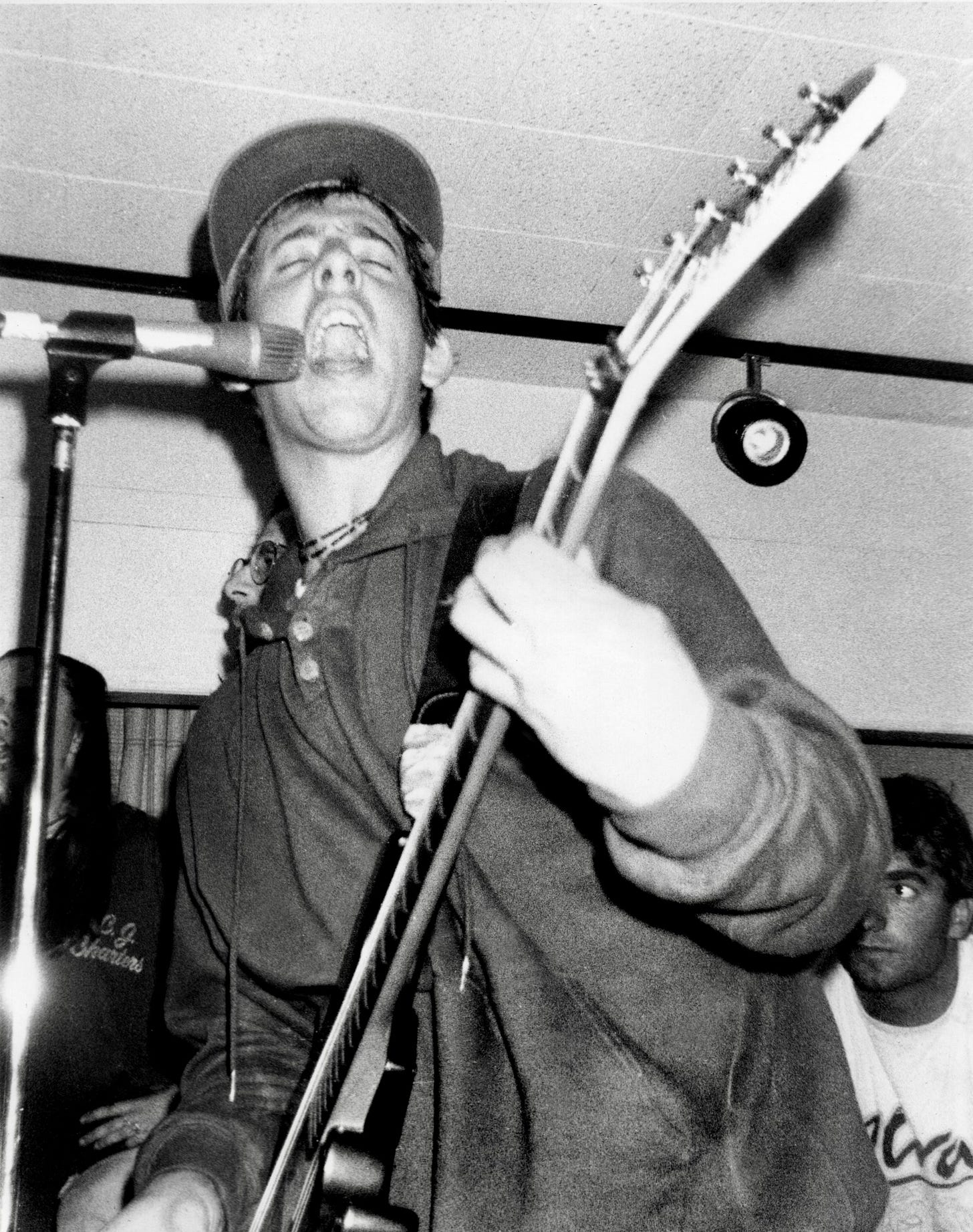

In Conversation: Richie Birkenhead of Into Another

For the second edition of Anti-Matter's "reunion interview" series, Richie and I venture out to discover how much we’ve evolved over the past 29 years. As it turns out, a lot.

Richie Birkenhead and I only knew each other marginally when we met for our first Anti-Matter interview in 1994. Our bands played shows together and we had close mutual friends, but that interview was the first time we ever really talked. Which is why I was so surprised that it got so real, so fast. I’ve already written about how Richie’s openness about going to therapy put me on a track that may have saved my life, but that original interview was also the first time I publicly brushed up against matters of grief and surviving abuse—issues I’ve been trying to work through my entire life—if even only a little.

When I thought about doing a second “reunion interview” with someone from the original zine, Richie was an obvious choice. Not only is he incredibly smart and articulate, but he has always been self-aware enough to do this kind of retrospective work honestly. It’s part of why we’ve always loved him.

I’ve only done one of these 30th anniversary interviews so far, but I’ve been reading the old interviews in general and I was thinking ours was actually pretty sophisticated, considering who we were and where we were at that point in our lives. The first thing we really talked about in that interview was the reputation you had back then for having a history of violence. Obviously, anyone who has ever known you in the last 30 years wouldn’t understand that, and you definitely felt bothered by it back then.

RICHIE: Yeah, I am still bothered by it.

Well, let’s go back to that then. Was there a moment when you thought, “I really need to change?”

RICHIE: Yes. That’s a daily moment, or even multiple moments daily, still. I mean, I know you know that a lot of this supposed reputation comes from distortions or a game of telephone, but some of it was warranted. I was certainly never a bully, nor was I ever one to pick fights. But I think my short temper, a lot of that was the result of growing up in a violent home with an alcoholic father and a lot of emotional chaos—beyond emotional instability. Like a lot of kids in this subculture, I was carrying around a lot of pent-up, unprocessed rage. So every once in a while, the safety valves would fail and there were a few episodes. But I was not someone who actively sought out violence. I tended to be more of a defender of my friends and loved ones.

You mentioned your dad in the original interview, but in a different context and not related to this part of the conversation, so that feels interesting to me because you didn’t seem to make that connection to the violence back then—or at least want to make the connection. That’s a real point of commonality for me, because at that time, I was denial about growing up with an abusive and violent mother. I constantly made excuses for her, like, “Oh, that’s not abuse, she’s from a different generation” or “That’s not abuse, it’s a cultural thing.” Were you also making excuses for what happened?

RICHIE: Oh yeah. In fact, I never called what I experienced abuse until I was in my late twenties, I think. Throughout my life, I made excuses for those things, and it was the same kind of thing. You know, it’s “a generational thing” or it was more of an “old world sensibility” or I was “grateful for some of the toughness that it instilled in me.” I made a shitload of excuses.

It took years for me to get to a place where I was like, “No. That was actually just wrong.”

RICHIE: Yeah, exactly. Actually, two years ago, my father passed away and it was kind of a big catharsis, that whole process. And also, I was surprised by the complexity of feelings. It wasn’t just, “Good. Rot in hell, motherfucker.” It was a very complex and nuanced cocktail of emotions that I’m still processing.

One thing that’s sort of coming to me on the spot about this question of how long it took for me to identify my abuse is how this interview took place in 1994, and my awakening about this was in 1998, and it happened because I had a godchild. I had this experience where they drew on my couch with a Sharpie, and they looked at me with this mortified look, like, “Oh my God, you’re going to be so mad!” But I was like, “No! Of course, don’t worry about it. I love you.” I walked out of the room and two thoughts came to mind: First, that my mother would have beaten the living shit out of me. And secondly, “Wow. I can’t even imagine treating a tiny, defenseless child like that.” That empathy completely reframed everything to where I was like, “Beating a child is wrong, period. What I experienced was wrong, period.” So I’m wondering how much fatherhood has enlightened you or given you insight into your childhood now.

RICHIE: A great deal. But I think I actively, even subconsciously, always endeavored to be the antithesis of my father—to not drink, for instance. And although there was the aforementioned violence that was usually meted out to strangers, I like to think I’m a kind and compassionate person, and it’s been a very, very long time since there’s been any violence in my life.

I have a fourteen-year-old daughter and an eleven-year-old son. I went through so many of those moments when they were very young, where they would do something that, for me, would have incurred a beating or verbal humiliation beyond belief. But same as you, I was like, “It’s fine. These are just things.” I don’t want to say it “enlightened me,” because that sounds kind of self-aggrandizing, but what I think parenthood has done for me—and I’m so grateful for this—is that it’s allowed me to experience a childhood I never had. I was robbed of my innocence at a very, very young age. And I mean really robbed of it. From age seven on, there was nothing I hadn’t seen or experienced, and there was a lot of darkness that [my children] will never experience. But I get to experience the wonder and the naiveté, the proper trajectory and all of the right milestones at the right points in that timeline. And that’s incredible. I’m still experiencing that.

I’m remembering the way that Youth Of Today rewrote “We Just Might” to become “Time To Forgive,” and as we talk about this stuff, I’m thinking about that because it’s one thing for a person to say, “Maybe I was wrong and maybe I need to change.” But it’s another thing to be in a hardcore band and to rewrite the lyrics to a song to say, “We were wrong and we’re going to change.” I’m not sure I fully appreciated the way they did that before just now, because I think we can be really stubborn in this scene.

RICHIE: I mean, if you look at the whole idea of being “stabbed in the back” or those tenets of hardcore or the straightedge credo that we all held onto—I don’t know if stubbornness is the right word, but sure, I think a lot of us were young and we had that incredible energy of youth, and a lot of that can come off as arrogant or stubborn. But I think it was more the resolve we had, because we were a tiny minority of what most young people were doing, and I think we felt proud of that. So yeah, a lot of us dug our heels in.

As far as “We Just Might” and “Time to Forgive,” though, just as pure theater, “We Just Might” is cooler, right? Like, we all love violent R-rated films and things that are sensationalist, but also things that just give a little bit of catharsis without actually hurting anyone. So at the time, part of me lamented the change in those lyrics because I wanted to be on stage singing along to, “You say you want to fucking fight?!” [laughs] But I think [Ray] Cappo was incredibly brave to do that, to rewrite those lyrics. I really admired him for doing that.

I remember actually reciting the lyrics to “We Just Might” to my daughter once—you know, “You come drunk to the show, looking for a fight”—and I remember when I got to the line that said, “Take a look at yourself, you’re a fucking mess,” my daughter was like, “That’s really mean, Dad! You don’t know what that guy’s problems are.”

I mean, has she heard “Say It To My Face”?

RICHIE: That was years ago, so she’s heard it all now. She’s actually been to some of these silly Underdog reunion shows and heard it live, so yeah.

How does it feel to sing a song like that in your later era?

RICHIE: It’s a mix. It’s like, wow, look at this middle-aged man up on the stage screaming this teen angst. Part of it feels great because it’s this thing that has endured and still has some appeal to some small group of people. But also, I feel so far removed from it by decades and by experiences, so part of it feels like theater—like you’re feigning this rage, you know? I mean, there’s still a lot of fire inside [of me], but it’s not just blind rage.

In the original interview, I asked you to tell me something about yourself that I wouldn’t know unless you told me and you said that you’d just come back from therapy. I didn’t know anyone who was open about going to therapy in 1994. There was definitely a stigma. Nobody wanted to be “the crazy person,” and even in this interview at some point you sort of sigh, like, “God, people are going to think I’m a fucking mess” [laughs]. So I’m a little curious, was therapy something you were pretty open about with everyone back then or did you just throw that out there?

RICHIE: I just sort of threw it out there. That actually ended up being an unfortunately brief stint, although I picked it up again later in life. But at that point in my life, for the first time, I realized I needed to deal with things I’d experienced as a kid—things I’d survived. It was kind of do or die at that point, literally, but that was a brief stint, and sadly, not with the right person. But I found my way back. I can’t say that it’s something I do that often, but it really helps me to be able to have a sounding board with someone who has a deep knowledge and experience in areas that I can benefit from. It’s not something I share a lot, but for some reason, Norm, I feel incredibly candid around you. I don’t know why [laughs].

It’s funny. It seemed like such a passing thing that you said, but it just affected me in a deep way, because I was like, “Oh. There are ways for me to work out these things that I’m trying to deal with.” It was such a positive thing. But I suppose there were a lot of positive things that I sort of ignored or took for granted at that time.

RICHIE: We take a lot for granted. I think we… Well, I can speak for myself. I catch myself sometimes taking for granted a lot of the magic that we lived through, a lot of the things we saw and experienced when we were younger. And when I look at the changed landscape, particularly culturally, and what lies ahead for my kids, there are certain things that I believe have changed for the worse. And some of those things really worry me. I really hope there’s some equivalent of another age of enlightenment or something tantamount to that, something to wake up humanity culturally. But there are a lot of obstacles to that ever happening.

We saw some really special stuff and we were a part of something that was a real moment in time. I know we all love to say it’s still going on—and it’s true, it definitely is, and there’s a vibrant culture as it pertains to hardcore and the satellite movements of hardcore. But when we last spoke [for Anti-Matter], it was at the very, very embryonic stage of the digital age. And what that did to regional culture, I think, is a bit tragic. It killed regional culture. The world has become so homogenized that you almost can’t have the necessary vacuum for a regional culture to form. It still happens, don’t get me wrong; there are definitely little pockets of incredible magic going on in all subcultures. But in the mainstream, it’s a problem. And we’ve also become so impatient and desensitized and such babies who need immediate gratification that I don’t think we can acquire taste for true visionaries anymore. I don’t think people, at large, can acquire a taste for anyone who isn’t photogenic and doesn’t sing with perfect intonation or has a timbre to their voice that makes you feel uncomfortable.

Obviously, you are aware of your idiosyncratic voice [laughs].

RICHIE: Oh yeah, I know it. I’m very aware of it. I have this kind of adenoidal, idiosyncratic voice, and that’s part of my catharsis as a singer—just owning that. I’m aware of my weird voice and comfortable with it, mostly.

OK, let’s talk about being weird for a second. Because I’ve always thought about Into Another as this sort of test for the Overton Window of hardcore. There were a lot of bands at that time that were doing their best to pry that window open with what you could get away with playing.

RICHIE: Yeah, that wasn’t the brief with Into Another. Drew and I were actively—and not out of any feelings of ill will or anything—but we were really trying to extricate ourselves from having to conform to anything. We would joke, as we were just coming up with what Into Another was going to be, about the fact that we were just going to alienate and put off so many people.

But you were pretty embraced.

RICHIE: We were unbelievably surprised that we were embraced to the degree that we were. That was so strange to us! I mean, look, there was a lot of heaviness and there was a lot of intensity. And certainly I was writing the most honest lyrics I’d ever written. So it did resonate with some people. I’ve always believed in the old adage that the opposite of love is indifference, so I kind of liked the fact that we were loved or hated. And I was always grateful and pleasantly surprised when we’d go to the West Coast and, like, the Sloth Crew kids were stagediving. But if we wanted to channel Marc Bolan or Bowie or George Jones or Ozzy Osbourne, nothing was off the table. It was just a total freeform stream of consciousness, no allegiance to any genre.

The original intro that I wrote to go with this interview in the zine begins, “When the first Into Another record came out, I hated it…”

RICHIE: Oh, I remember that! [laughs]. But that’s what we were going for.

No one starts a band to be hated. Clearly you thought there was an audience for what you were doing.

RICHIE: Not to be hated; it was just complete abandon, almost with a smirk. Just letting it rip. It was to create in a way that was totally unbridled and unhindered and not care about how it was perceived.

And at the same time, in that interview in 1994, you really expressed this very real distaste for feeling misunderstood or misrepresented.

RICHIE: Yeah, that’s something that has definitely waned. I let go. You can’t control the way you’re perceived. And I’ve had enough people who have told me how words I wrote resonated with them, or ways in which I was relatable to them, to where I don’t really care anymore about being misunderstood. Just the intrinsic narcissism in that is something that I’m well past. All vestiges of narcissism or vanity have left. I just smile at it all now.

I did believe then that I had so much to say. We all do, and what I have to say isn’t above what any other human being has to say. I think that any kind of artist or writer or poet, you always want to arrive at a place where you have an honest and unique voice, right? An artistic voice. I felt that I had gotten to that place at some point in the ‘90s, and I really did feel like I wanted to share this with you all and I wanted you to get all the humor and all of the irony and all of the subtlety and anger and sadness—I wanted you all to understand it. But I don’t feel that anymore.

I found this weird book about Disney that was written by an editor of Breitbart—like, it was this culture war thing where he was trying to demonize the company as not being family-friendly or something. But there was a section about Hollywood Records and a paragraph about Into Another that was wild. It said: “The Hollywood Records promotional literature for the band Into Another includes an interview with vocalist Richie Birkenhead discussing his wild reputation. ‘A few months ago,’ he brags, ‘I heard a rumor that I was on stage and had done so much cocaine that my nose exploded into a bloody mess and I had to have plastic surgery. That was a pretty good one.’” Do you have any memory of saying that?

RICHIE: No, but I must have been absolutely taking the piss if that did happen. Wow. I don’t remember any interview with me being part of any kind of press kit at Hollywood Records. But for the record, no, I didn’t do cocaine and at no time was my nose close to exploding [laughs]. It’s funny though because I do know all the ways that [Hollywood] did fuck us up—like releasing our CD in regions outside of North America with another band’s music on the disc. Instead of Into Another’s Seemless, there was some trance band’s music on it. Things like that. I know what happened and what didn’t happen.

You hadn’t even signed your record deal when we did this original interview, so I don’t even really know. What exactly happened?

RICHIE: It was a cavalcade of unfortunate events, like a perfect storm. There started to be a lot of friction between us and the label. The guy who was running Hollywood Records at the time, Bob Pfeiffer, ended up hemorrhaging money for that label and just being an all-around disaster, and we butted heads. He would say things to me like, “A song title has to be the chorus of the song. It has to be something you repeat, that’s a song title.” And I was like, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” [laughs]. We just butted heads on everything.

We toured like crazy in those years leading up to the release in 1995. Leading up to the release, we were supposed to have gotten the green light to make a video we wanted to make for one of the songs. The song (“T.A.I.L.”) was charting in the Top 40 [on the Billboard Mainstream Rock Tracks chart] and the CD wasn’t available anywhere while the song was charting, nor had they given us the green light or the means to make the video to support the song. As you know, in those days you needed to do that. And even when they finally got around to making a video for a different song, for “Mutate Me,” we put it in their hands because they wanted to take care of mastering and they actually reduced the volume of the track! So when Matt Pinfield played it on 120 Minutes or whatever, it was at a quarter of the volume. I mean, everything went wrong. They had breached contract in so many ways. I hate to speak in legal ways about any of this stuff, but they had just fucked us up royally, and we finally did sue.

Unfortunately, they had just gotten through being sued by another band who got their masters back, went to Interscope, and went multiplatinum. So they were like, “If you start a litigation with us, we will keep you in this until you are old and gray. We will never give you your masters.” It was really as acrimonious and horrible as it could possibly be. So we ended up taking a settlement because they would have truly bankrupted all of us, but it was a tiny fraction of what they owed us contractually. I couldn’t perform or record for two years because I was part of a “key member clause” in the termination agreement. It was just awful. A really terrible experience. It was a slow death.

How did that affect your creative heart, for lack of a better term?

RICHIE: I wrote lots of very sad, slow songs meant for just my voice and an acoustic guitar and for my own kind of therapy. And most of those songs will never touch ears beyond mine and my immediate family. I went into kind of a dark place and I was everything you would expect. I was depressed. I mean, I turned to other things and I was still doing music and art, and I was getting into creative direction and design as a kind of salve on my wounds. But it was really surreal to know we couldn’t just go back into the studio and record something else and release it on another label. That’s when you really realize how evil the big machine can be.

I know people don’t like this word, but was there regret?

RICHIE: Sure. I mean, I didn’t regret signing with a major label. I didn’t think it was selling out. I always thought that was such fucking rubbish anyway. But yes, I regret signing with that label, sure. It was the wrong label.

Also, look, I did my part to fail as well. I wrote really long songs with a bunch of parts. I was a brooding, pretentious artiste. There are a myriad of other ways in which I’ve sabotaged myself. So I don’t point the finger of blame squarely at that record label [as if they] ended my music career. But they made a kind of temporary living hell for us that was really hard to navigate.

Do you think that a band in the style of Into Another and what you guys were doing were more susceptible to being excessive?

RICHIE: Well, not in the kind of artistic, self-indulgent way that irks me when I hear it. It was more in having so much contempt for formulaic, two-minute and forty second dreck. It was having so much contempt for that to where there was no middle ground for me. Which is weird because I actually grew up loving a lot of popular music. Not so much contemporary pop music beyond a few guilty pleasures, but the Great American Songbook. I grew up in a musical family and I could always appreciate a perfectly written standard. Not that I should have been doing that, but I think there was also a middle ground where I didn’t have to entertain every little folly and every little wild creative thought. A lot of stuff could have ended up on the cutting room floor, and things could have been a little leaner and tighter. So in that use of the word excessive, yes. But not in my definition of the self-indulgence of musical masturbation, no.

I don’t know to what degree it was true self-sabotage or it was just out of contempt for the big music machine, you know. Like, they hated that they struggled with the fact that we didn't know what genre we were. We were fine with it. But they were like, “We need to know how to sell you guys, how to market you.” And they never did know. And we didn’t know. But I did think I did shoot myself in the foot from many angles with, to your point, the musical and lyrical excesses.

In our original interview, we keep going back to talking about the death of loved ones—first when we talked about “Without a Medium,” and then later as well. It was interesting for me to read again because I told you about how I’d lost my best friend in a car accident in 1990, and thinking about now, I realize that this was only four years later. That was still really raw for me. You told me that losing friends made you scared to make the emotional investment in people, that you were worried it could end at any second, that it left you with a feeling of emptiness that’s hard to get over. Are these still things you feel?

RICHIE: Yes, for sure. And actually, I still mourn the death of my friend Jesse, who also died in 1990. But my feeling about the brevity of life, I think, has changed a bit in that I think what I’ve learned is to just really savor all of that time with people that I love and care about. Whereas back then, I felt so wounded that I was like, “Well, fuck it. What’s the point? People just die. They can be ripped away from you,” and now it’s like, “Just hold onto it. I could vanish tomorrow and anyone close to me could.” It’s more about being here now and just savoring all of those moments, the laughs and tears and hugs.

It occurred to me that I’ve never really heard you talk about Tony [Bono, Into Another’s bassist who died in 2002]. I wonder if that’s deliberate.

RICHIE: Tony is a very raw wound for me. I honestly can’t think of anyone else in memory who was as strangely pure as Tony was. Meaning all of the soap opera and the drama and the things that you and I have been inadvertently or sometimes willingly become a part of in this whole world, in this whole scene, he was literally devoid of any of that. He was all music and id and love and affection. He was just so sweet, so kind, so silly. And he was raw and uneducated and just coarse in the most endearing and amazing ways. I was so in awe of his musical ability, because so many of the riffs and the progressions that became songs that came out of him really resonated with me. They brought lyrics out in me that I didn’t know I was capable of writing. Tony was such a force of nature, and a lot of people say this when someone has died, but he was truly the backbone and the glue; he held it all together. He was a lot of what felt like, to me, the magic that we made. Talk about having a unique artistic voice. I don’t know any bass player who sounded like him or played like him to where even when he was playing a lot of notes with total virtuosity, it never sounded like overplaying. It was always appropriate to the song and to the moment in the song. He would lay such fertile ground for us.

He was incredible. But it’s still very painful for me to think about Tony or talk about him because I remember feeling so helpless. I had moved to L.A. and I was 3,000 miles away when I heard that he died. I felt so helpless being so far away. And I remember, rather than jump on a plane, just getting in my car with my best friend, Noah, who was visiting me in L.A. at that time. And I was like, “Let’s just drive straight back to New York. I gotta get back to Tony’s funeral.” And I did. I got there. I drove across the country and made it there during his funeral and then it just hit me. It just fucking poured out. I just hated the fact that the band had been broken up for years at that point, and we had all kind of scattered. He was like a member of my family. I felt closer to him at that time than my immediate family. It was intense and it’s still really hard to talk about. I took his death harder than any other in memory, really.

What was the state of your relationships with the band members at the time?

RICHIE: I mean, you know bands. There’s always little perceived slights and, like, resentments and weird things. I always remained very close with Drew. My relationship with Drew has always been this big brother-little brother intensely close relationship where we can just bare our souls to each other. Which is not to say that along the way we didn’t get into our little tiffs, of course we did.

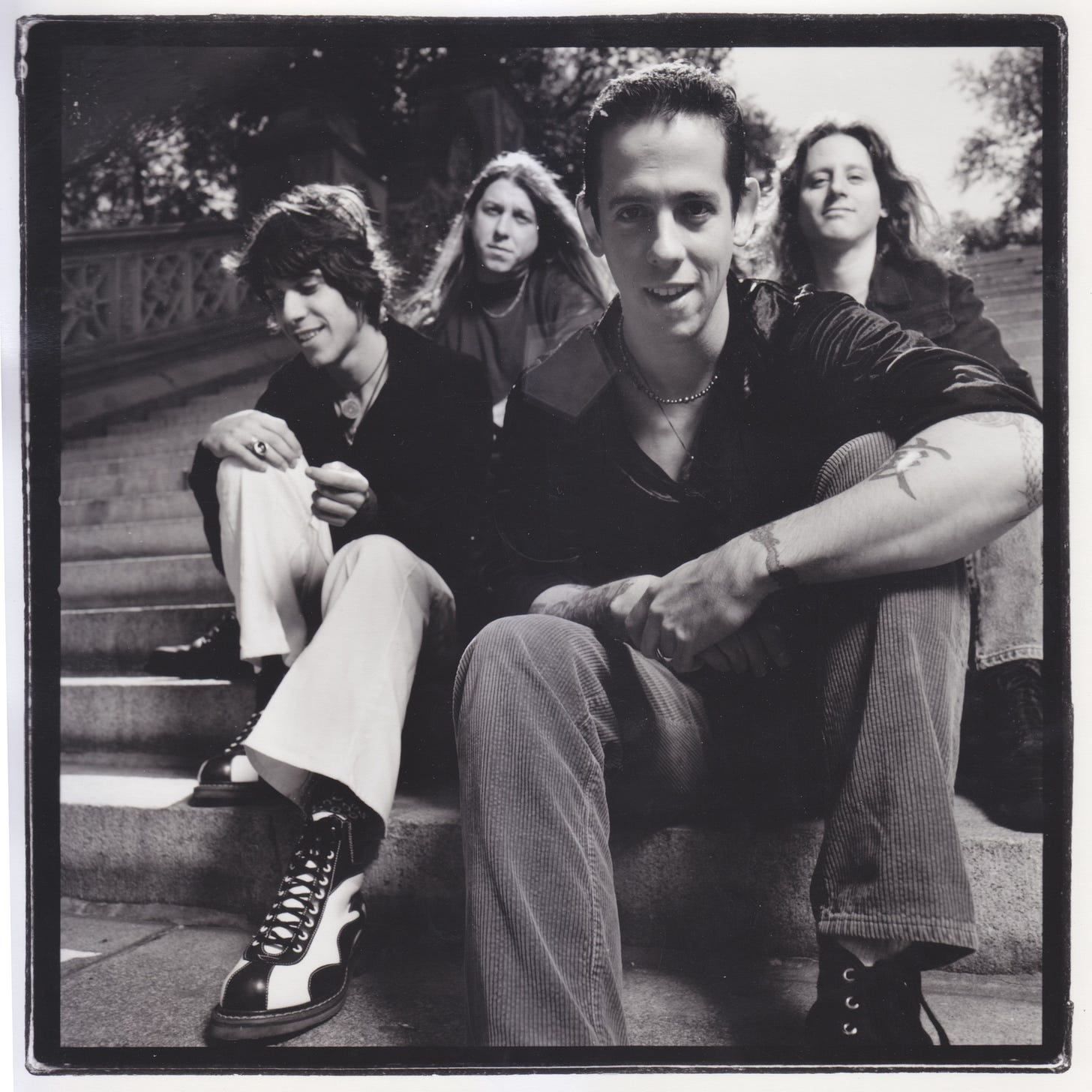

For whatever reason, Peter and I at that point in time kind of drifted apart and lost touch. I don’t even know why because when we got back in touch, which happened in 2012 before the Revelation [anniversary show] reunion stuff, we picked up right and we were just getting along beautifully. Peter and I are very close now, and we love each other, and Into Another is a thing that kind of exists in suspended animation. Every once in a while, we’ll get together. And we have Brian and Reid now, who are like family to us, too. They’ve been part of the band for eleven years now, going on twelve.

It feels like the genre-less-ness of Into Another is kind of a boon in the scope of longevity because it means that you can just be whatever the fuck you want to be whenever you want to be it.

RICHIE: That’s a great idea. I like that. It’s funny, you never know if what you’ve created stands the test of time. Maybe it doesn’t. Maybe it sounds incredibly dated or maybe it’s not relatable now. I don’t know. But the genre-less-ness is definitely what I guess we originally intended it to be—something that would never hinder us or pigeonhole us or narrow the scope of what we would be audacious enough to create. I wanted to spend my life making music and just focusing on that. I never desired fame or even to have more than I needed. I just want to be free from anxiety and free to create.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

The original Birkenhead interview was the most surprising from the original antimatter incarnation. I think it’s the ideal example of how an interviewer and subject can dance together.

Seeing you revisit each other 30 years later and pick up that dance where you left off was so cool.

"I remember actually reciting the lyrics to “We Just Might” to my daughter once—you know, “You come drunk to the show, looking for a fight”—and I remember when I got to the line that said, “Take a look at yourself, you’re a fucking mess,” my daughter was like, “That’s really mean, Dad! You don’t know what that guy’s problems are.”

Proof that she is clearly wise beyond her years.

I could easily write an essay on the death of regional culture but, I'd rather just type out that the original interview confirmed the soft spot I had for Richie was indeed valid and this reunion is a great reminder of that.