In Conversation: Pete Wentz of Fall Out Boy

Before he became a pop culture figure, Pete Wentz was a staple of Chicago's hardcore scene in the '90s. If you talk to him now, you'll know: His heart never left.

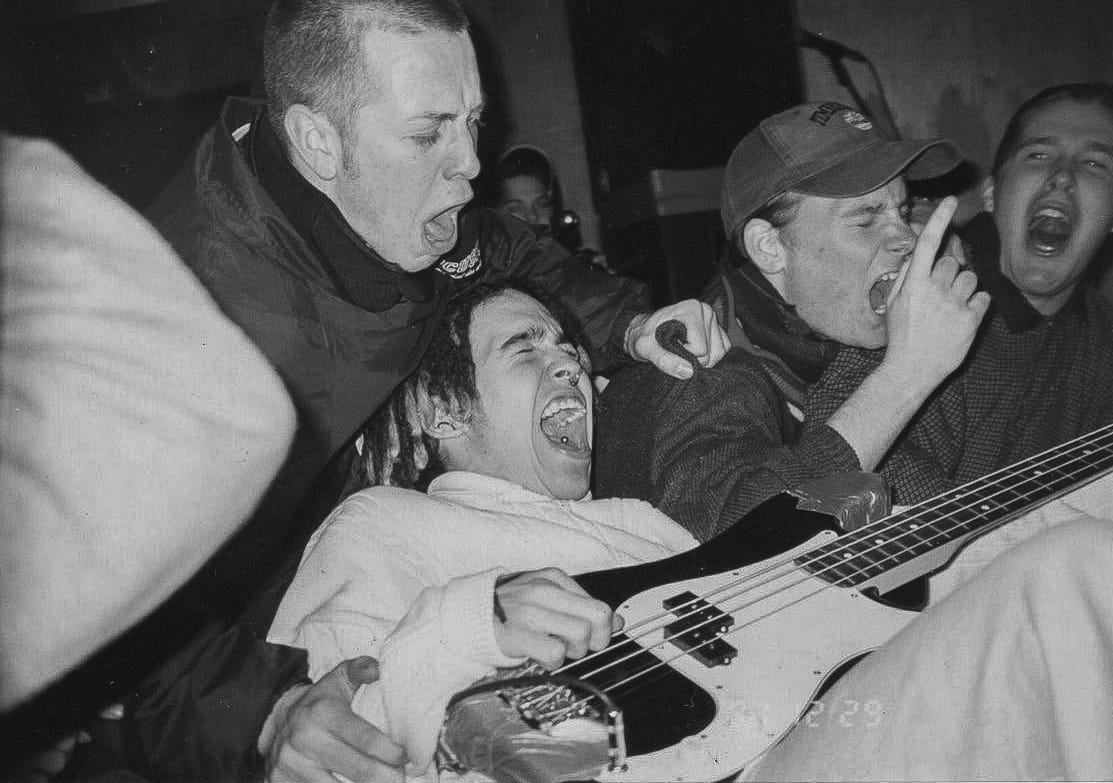

Before Fall Out Boy broke into the mainstream consciousness, I’d only ever met Pete Wentz once. I was living in Chicago in the late nineties, right after Texas is the Reason broke up, and I’d befriended a group of hardcore kids who all seemed to know each other from growing up in the suburbs. I went to see a band at the Metro with a couple of them, and then afterwards, we wandered into Pick Me Up—a nearby vegan café that seconded as a hangout for wayward straight-edge kids. Pete was already sitting in a booth. I slid in and said hello, but we didn’t really talk that much. No one in the scene at that time would have called Pete shy in the ‘90s—if anything, his membership in bands like Firstborn, Extinction, Birthright, Racetraitor, and Arma Angelus, to name a few, made him almost ubiquitous—but for some reason we both kept to ourselves that night.

Over the next decade, of course, Pete would go on to become the bassist, lyricist, and oftentimes mouthpiece for Fall Out Boy, a 30-million-album-selling stadium act. But behind the trappings of notoriety and fame, almost everyone I knew who had known Pete as a hardcore kid still talked about Pete as a hardcore kid. Mike D.C., who sang for Damnation A.D., told me about taking his kid to see Fall Out Boy just a couple of months ago and hanging out with Pete. My friend D.J. Rose, who was a significant player in building the Syracuse hardcore scene in the ‘90s, told me how Pete really came through for him as a friend not too long ago, at a time when he was going through a rough patch. Overwhelmingly, there was a portrait painted of a person who never lost sight of his friends and of the community that made him who he is—regardless of his life’s many twists and turns. This, too, is hardcore.

The other thing I kept hearing from mutual friends for months is that Pete loved reading Anti-Matter. So 25 years after our first and only meeting, Pete Wentz and I finally managed to get together for a long overdue conversation. “I would feel weird even calling this a fanzine, you know?” he tells me. “To me, it was making our thing real. It was making this thing where kids who were playing on a four-inch stage playing songs where there was no melody to the vocal—this thing that was magical and temporary—very real.”

I wasn’t planning to start this way, but this question literally just crossed my mind. When was the last time you actually did an interview with a hardcore fanzine?

PETE: That’s a good question! I’m not even sure I ever really have. Maybe when I was doing Arma Angelus there was something, but I don’t have a specific memory of it. Early Fall Out Boy days we probably did a couple. But for me, in the heyday of ‘90s zines, any time I was in bands at the time, I was definitely not the mouthpiece of the band at all. So I wouldn’t have been the person answering any questions—thankfully [laughs].

Talking to you now, I’m thinking that you seem like the kind of person who would have done a zine.

PETE: Yeah. I did do a zine. I did multiple zines. The one that I remember the most was called XDarkSideX. And I only really remember it because our drummer, Andy [Hurley], showed me this thing where I apparently did a “Death of a Zine / Rebirth of a Zine” thing for all my readership [laughs]. More often than not, though, I would always do joke zines with the guys from Kill the Slave Master. We would do zines for stuff that we thought was funny, but it was so specific and so niche that I don’t even know who would read it. Those are the ones I liked the most.

OK. Getting serious now, this is going to be the last “normal” interview I’m going to be doing for Anti-Matter for the moment…

PETE: Death and rebirth! If you need any help on it, I’ve done a zine!

I might need the insight! [laughs] Anyway, one of the reasons why I chose to do this interview with you specifically is because exactly one year ago, Pitchfork did a feature on Anti-Matter, and… Well, I’ll just read you the excerpt:

[Brannon] embraces finding the connective tissue between the various pockets of the community, and keeps an open mind about which members’ perspectives deserve to be celebrated. That extends to the people he chooses to feature in Anti-Matter, and when asked who’s currently at the top of his interview wishlist, he delivers an answer that’s sure to rile up purists: Pete Wentz of Fall Out Boy.

He goes on to quote me calling you “a dyed-in-the-wool hardcore kid,” which I qualified by saying specifically that I believe being a hardcore kid is “very much a way of being—I can’t define that for anybody else, but I know it when I see it.” So I wanted to start here by asking you if that premise is something you’d agree with.

PETE: I totally ascribe to that. There are definitely things that you could look at—about the ethics [of something] or the way something looks or how it looks not like other things—and you know: That’s hardcore.

I think a lot about when I was most in the daily life of hardcore, in the nineties when that was all I thought about. There was something within this pre-internet—or at least early stages of the internet—version of the culture, where there was a true DIY quality to it, but not in terms of the way I think people use “DIY” now. I think people sometimes use DIY now [to suggest something] looks shitty because it was “doing it yourself.” But in the nineties, in hardcore, I think it was quite the opposite. It was just like, “Well, I’ll start a record label” or “I’ll learn how to tour manage a band” or “I’ll make the cover glossy” or “I’ll learn Photoshop.” It was aspirational! It was like, we’ll just make our own thing; we don’t need this other thing. That was a heavy takeaway from that period to me, mentally. It felt like Boy Scouts in the woods learning how to make a campfire. The hardcore equivalent to that was Book Your Own Fuckin’ Life. You could figure it out. And that has paved the way for everything for our band—and even for the way I look at other [hardcore] people: “These things all fed into what you became.” I don’t know if that’s really the answer to your question, but that’s kind of the way I look at it.

I mean, that actually really resonates with Anti-Matter, specifically. I do think the physical zine got a lot of attention in 1993 because people thought it looked “pro.” But in reality, it was me and my friend at his father’s office in the middle of the night trying to figure out how to use QuarkXPress [laughs]. Apparently we did a good job. But part of it was that we were not getting validation anywhere else, so it was like: Make your own validation. I was trying to make the zine look a certain way aesthetically because I thought that maybe if it looked more quote-unquote “pro,” it would get taken more seriously—and by extension, that maybe the bands I was interviewing would also get taken seriously.

PETE: Totally. And, I mean, this was serious to me. These bands were serious and important to me—and important to all of us. And I wanted the world to take that seriously. I wanted that when my parents saw an Earth Crisis shirt on me, that they’d know this band was important to me and we could talk about it.

Also, I would personally be looking at Anti-Matter or Second Nature or something like that, and I was like, These look like magazines. I would feel weird even calling this a fanzine because they looked like real magazines, you know? To me, that was so cool because it was making our thing real. It was making this thing where kids who were playing on a four-inch stage playing songs where there was no melody to the vocal—this thing that was magical and temporary—very real.

Since this is the last proper interview before end-of-year stuff and then the hiatus, I also wanted to bring back a couple of questions that I think really defined this iteration of Anti-Matter for me, and this one is near and dear to my heart. It started early on when I asked Crystal [Pak] from Initiate this question, but it seems to have resonated with people. I told her about how when I first started going to shows in the eighties, and how when I started meeting kids for the first time, I found myself frequently asking them, “So, what fucked you up to be here?”—and there was always an answer. You and I only met for a minute in the late ‘90s, but had we gone into a real discussion and I’d asked you that, how do you think you would have answered it?

PETE: This is something me and Patrick [Stump] and the band have talked about on a bigger level, but for me, specifically, I grew up in the suburbs of Chicago. The Breakfast Club was my high school; it was literally the high school I went to. Every one of those movies took place in that town. Also, I am mixed race. My mom’s parents are from Jamaica and my dad’s white, and they were super liberal and we were in a pretty conservative area. So I think I just didn’t really know where I fit in. I kind of didn’t really feel like I fit in anywhere.

At one point I got really into death metal. I had a friend with an older brother who had the Metallica mixtape—it was always the older brother’s mixtape, right?—and in that skate-metal culture, it was like, “What’s the most extreme version of all of it?” So that [mixtape] led to Cannibal Corpse and Sepultura and all that. One day I was in a freshman class, I can’t remember what class it was, and I was wearing a Sepultura shirt and this kid was like, “Yeah, but can you do a hardcore growl?” [laughs]. I was like, “I don’t know what that is!” So we went to a show that was in a garage in Kenworth [Illinois]. I think it was this band Everlast. I just remember people singing into the mic instead of the singer, grabbing the mic, and it just felt like, “What is this?” It felt like this deep thing that I knew nothing about. It was like peering inside of an ant colony or something. There’s like all these levels to it and none of it makes sense to me.

From there I think I realized that in Chicago, in that scene specifically, there were so many different kinds of people that it felt like, OK, maybe you didn’t fit in, but maybe we could all not fit in—in the same place. So I guess it wasn’t a specific trauma, but it was the feeling of not knowing my place and then having a place. And having a place where you can hear discourse and be a part of discourse. To me, there was nothing like nineties hardcore in that there was so much discourse and there were so many ideas. There were so many good ones and so many bad ones and they were all clashing around rooms. But it was a place where you could feel like you fit in and you could talk. It all felt really thoughtful.

I kind of want to go back to the point you made about being biracial, but first I need to know, did you read the essay I wrote for Amy Madden’s book [Negatives]?

PETE: I don’t think I did.

You’re kind of the star of it in some ways [laughs].

PETE: Oh damn, OK!

The book is really well done. I’ll try to quickly summarize it, but essentially, I wrote an essay about the erasure of people of color, women, and queer people in second- and third-wave emo, which is the focus of the book. I try to stress how much we’ve all contributed to not just the second- and third-wave, but also the first wave. And I book-ended the essay with two stories: The first story talks about how I met a magazine editor once, who was cool, but who later posted a blog about meeting me where he said, “I never knew Norm wasn’t caucasian!”—and how that was the first time I really started to understand that making this kind of music can often come with the assumption of whiteness. And I talked about how that made me feel. In the second story, I talk about that time in 2020, when you started trending on Twitter after Fall Out Boy did a [Black Lives Matter] post and it seemed like everyone had just discovered you were biracial and it felt like this huge shock. Again, they were suffering from the assumption of whiteness. I was like, “I feel you, Pete!” [laughs] Have you ever struggled with knowing how you’ve been misperceived?

PETE: This is an interesting question for me. It’s so complex for me. I think it’s a specific thing with being biracial that I just didn’t feel like I fit in anywhere. Like, never white enough, never Black enough, never Jamaican enough, you know?

I think I get what you’re trying to say. Like, my complexity is that my family were immigrants and obsessed with the American Dream. They forbid me to speak Spanish, for example. So there are pieces of my culture that I feel disconnected from because they didn’t allow it. They wanted me to be American. But does that make me “less” Latino? No. I don’t think so.

PETE: Growing up, I think my family was the “weird” family that would go get Ethiopian food and then go to a musical. And I was like, “I just want to go to McDonald’s and do the normal things” [laughs]. But now I appreciate it. I have that appreciation. At the time, I didn’t want to stand out. I just wanted the basic things that the people on either side of my house were doing.

In some ways, one of the things I love—and I know I keep going back to nineties hardcore, and it’s probably in a nostalgic way—but I feel like in Chicago especially, shows had ska bands and punk bands and pop-punk bands and hardcore bands. There were political ones and not-political ones. There were all kinds of different people and cultures. But I do agree that if you were not white, then theoretically you probably weren’t going to find somebody of the exact same archetype as you. But there were other “others.” And that was one of the things I loved about it. At those shows I didn’t really think about it. Maybe I would think about it when you’re filling out a standardized test and they’re like, “What race are you?” And I’m like, “I don’t know! What do you want me to be?” [laughs]

I’ve struggled with that question on forms as well.

PETE: Right?

This is related in the sense that, as I’ve been thinking about winding down this zine for now, I’ve also been thinking a lot about what I call “being perceived.” And one of things that I am feeling a little bit relieved about is that I’ve realized that doing this public-facing thing every week makes me feel kind of exposed at times. I’ve just realized over the last 30 years that I’m not actually very good at receiving attention. I might be simultaneously attention-seeking in some ways and then also cringing at the attention. I’ve never been able to reconcile the two.

PETE: Yeah, totally.

So if I’m being honest, having had friends become famous, I always knew: I didn’t want that. What would you say your initial response was to that high level of being perceived?

PETE: I know it probably doesn’t feel like it, but there was a gradualness to it in the sense that first we would tour and there would literally be no one at any of the shows. No one. And then there would be the local band watching us. And then people were singing the words. And it wasn’t until we’d play shows and every time we played the fire marshal would come and shut the show down that it was like, “Oh. That’s a thing.” But I think that the summer of 2005, when we were on Warped Tour with My Chemical Romance, that was a time when there was a void of boy-bands within pop culture. And it was almost like we filled in that void for that summer, or for a couple of years. That was the time that I remember going from being able to go to catering and it being whatever to stepping off the bus and there’s just people. That was that explosive moment.

On one level, there was this feeling of validation—of believing in the thing that you’re doing so much that you’re dropping out of college, and you’re putting all your chips on this thing. There’s a validation that someone else sees it; it wasn’t just this crazy pipe dream. We worked so hard and so counter-intuitively, and we were told no by so many people, that we felt validated. All my memories are so compressed because we did so much, but it was maybe that next year where it started: You couldn’t leave your hotel. And you would [have to] go in through the kitchen. That level? That was the closest level our band would have to a boy-band or something like that. That level, I was like, “I don’t like that.” I have an appreciation for the love that people have for the art, but to get to the point where it’s like, I don’t leave my hotel room… When you don’t leave your hotel room, there’s a lot of loneliness.

Talking beyond the art—because that’s the most important part of it to me—but being at the level where you can just call a restaurant and get a reservation, that’s a great level. Anything beyond that is excessive. What you gain is not worth what you miss out on.

There was a time in 2009 when I think Fall Out Boy went on hiatus. And I remember you had a famous line from that time where you said something like, “I think the world needs a little less Pete Wentz right now”—a brilliant line, by the way [laughs]. You retreated for some time after that. How did you use that time? Did you do some personal work to address everything that had happened to you in the previous decade?

PETE: I did so much work. I’ll be honest. My whole life just kind of blew up at the same time. I had a divorce, I had a kid. You’ve been in a lot of bands, and I don’t know if you’ve had this experience—maybe you had this experience with the zine—but so much of who you are is built up in the thing that people know you from, so if that thing goes away, it’s like, what am I? What even am I? I put so much time and thought into this that I don’t even really know. Am even a separate entity from the thing?

It was a little heartbreaking for me in the way that the perception of me had become bigger than the band. And I think it hurt the band. Like, I think Patrick’s musicality is really off the charts. And I think it was damaging to have it be reduced to this tabloid culture kind of thing. For me, also, I don’t really know how to explain how much you atrophy in things. Like, I didn’t know how to go through the airport. I followed a backpack through the airport. I literally didn’t know to go check-in and put your bag in and then see your gate. There would just be a backpack in front of me with the security guy and I would literally just follow it through the airport. So I think having a kid and kind of losing that part of my identity forced me to go and be like: Now you’ve got to be an adult. A real adult. There’s no backpack to follow through the airport anymore. You need to raise a child and that’s not going to work with all these atrophied qualities. So that was super important to me.

And then I think being in a band—you know this—it’s so hard to describe to people what it’s like. Because it’s like being with your siblings at Thanksgiving forever. But it’s also like being on a submarine with them at Thanksgiving, right? And you can only go to the other end of the submarine when you fight or something. You push each other’s buttons, but they’re the only other people that have shared this specific life experience with you, so you’ve got to talk about it. Going back and doing it again, we wanted to do it in a healthy way—where we talk to each other and we don’t push each other’s buttons and we do it more adult-ish. The great thing about saying “the world needs a little less of this” is that the world does move on. Time does move on. And to me the second era of Fall Out Boy was way more focused on the songs and the art of it—as it was in the beginning, too. That was always the goal of the band.

Do you think growing up with hardcore idealism complicated the way you experienced that?

PETE: That’s a good question. I loved hardcore so much. In the nineties, it was so formative. But I think around [the time of] the formation of the band, the spirit of it changed to me. This is such a bigger conversation that it will feel weird to widdle it down, but hardcore is like a microcosm of the bigger culture: sometimes it’s rebelling against it and sometimes it’s flowing with it. But when it became less idea-driven [in the early 2000s], I didn’t love it. That’s why we wanted to do the melodic band. It was fun. It wasn’t fun when we would go to shows and every band kind of said a similar thing and it was always about moshing or whatever. That’s in the inception of [Fall Out Boy]: We were like, let’s do something fun that’s not that.

It always fascinated me how Arma Angelus somehow morphed into Fall Out Boy like that.

PETE: On the [Arma Angelus] album, we did this melodic… Cheap Trick cover. And it was like, “Oh, this is kind of fun. If there was somebody that could actually sing it, this would be really fun.”

That version sounds like Negative Approach to me. I don’t know if anyone has ever said that to you.

PETE: No! That’s cool [laughs]. It was just something that was a lark. I just remembered this, actually, but you know how sometimes after band practice where people switch instruments and you’re like, “Let’s play Rancid covers,” or whatever it is? That’s kind of what Fall Out Boy was initially. It was the after-band. But it’s like the thing we talked about earlier: The two biggest influences for us, basically, were that do-it-yourself Book Your Own Fuckin’ Life, and then I would look at bands like the ones that you [and your peers] were in. I was like, these guys play at the Metro. They have choruses. You know what I mean? These are real bands. It made such an impression on us.

I was trying to think of how to define what the Chicago hardcore scene was for me at the time, and it was a little bit like those mix-and-match kids’ books—where you can put a lion head on a giraffe body with rhinoceros legs. There just weren’t enough shows for there to be only a hardcore show, usually. So you would have the Blue Meanies around and then Damnation [A.D.] would play with Lifetime, you know? And what I took away from that is that there doesn’t really need to be genres. The world hadn’t started trending that way yet, but it would start trending that way. And we just had the advantage of doing that while the world trended that way at the same time. To me, it was just so influential to know that all these different types of music could coexist.

Early on you called Fall Out Boy “hardcore kids that are writing pop music.” Do you still feel like hardcore somehow creeps into your approach?

PETE: I totally think it does. I think more so in the way that we discuss things with each other, whether it be the music itself or the ideas around the stuff. We’re mining what we’ve watched our friends do within the hardcore scene when we’re talking about it. To me, with our band, there are certain things we agree on music-wise, and a lot of that stuff is really trapped within those formative years—and that time of hardcore. Like, Patrick… This is so ridiculous, but he is always referencing hardcore-band snare [drums]. He’s like, “We need the Snapcase snare!” Or like, “We need the Chokehold snare on the ‘We’re Not Gonna Take It’ cover, but recorded better!” And I’m like, no one else knows these references! [laughs]

One of the reasons I think that it’s harder to pin down a documentary from that time is because everyone mixed and matched [their version of hardcore] based on the region they lived in, and also because the internet wasn’t so prevalent. So sometimes you would go to the record store and they would only have the Insight 7-inch. Or it would be like, “You like Frail and I like Honeywell” [laughs]. Everyone’s version and perspective is so specific to them, and that’s what it’s like for our band at least. We talk about all those references.

OK, I wanted to end this with a question that I’ve actually asked a few people, but so far I’ve only ever actually published the answer from one person. The only person who did this question right was Ned [Russin] from Title Fight. But I feel like you’re the kind of guy who is going to do this right.

PETE: OK, we’ll see! [laughs]

I want you to tell me something very banal about yourself that you believe says the most about who you are.

PETE: Oh. This is a good question… [Pauses] OK, I’ll tell you. This is just true. The other day I was speaking to [my partner] Meagan, and I was telling her that the times that I feel the most zen are when I’m driving our kids to school. She was like, “There is no way that’s the case. Because you are sitting in traffic, and then you’re rushing to feed them, and then you wait in line to drop them off, and then you go to the next activity—and they don’t want to go to the next activity—and you’re sitting in traffic in Los Angeles the whole time. It’s literally the least zen.”

But for me, it’s just the most normal thing that I do. I’m not thinking about whether or not the pulley that pulls me up on the stage is going to break, and then I’m going to be stuck 30 feet in the air. I’m not thinking, “This is the time I need to go to sleep because lobby call is at that time and if I don’t get enough sleep, then…” No. I’m just sitting in traffic, listening to Taylor Swift, driving my kids. She just doesn’t believe it, but it’s the most zen I could ever feel. And I think that’s really definitive of who I am as a person.

It makes sense to me because you’re basically saying that’s the time when you are in the most controlled situation where you have no control. You just have to sit there. That’s all you have to do.

PETE: You only have to sit there and get your passenger to the place they need to go. And I think most of my life is spent doing the opposite. I am the passenger and someone else is doing that for me. But in this situation, I’m like, No. I’m the person. I’m driving you. And there’s something I truly love about that.

That’s perfect, thank you.

PETE: I also want to say real quick: Nineties hardcore t-shirts are peaking right now. The fabric is as good as they could ever be [laughs].

I have noticed your t-shirt game on Instagram lately and I should admit that I have had conversations with people where we’re like, “Does he really love Mean Season and Billingsgate?”

PETE: I love Mean Season! That’s what I’m talking about! People are always like, “There’s no way anyone likes that music! You don’t like Brothers Keeper!” But dude. I love Brothers Keeper.

Anti-Matter is ad-free, anti-algorithm, and all about hardcore. For updates on its future, please consider subscribing now. ✨

Snapcase snare forever.

me and pete wentz, the only two people in the world who truly love bro keeps