In Conversation: Kent McClard

With fanzines like No Answers and HeartattaCk or his influential Ebullition label, Kent McClard has spent 40 years keeping hardcore accessible for future generations. There was no other path, he says.

Programming Note: Don’t forget that the Anti-Matter merch drop presale is only live until July 19. Once the store closes, these designs are gone. Check it out now, and please support this work if you can. Thank you!

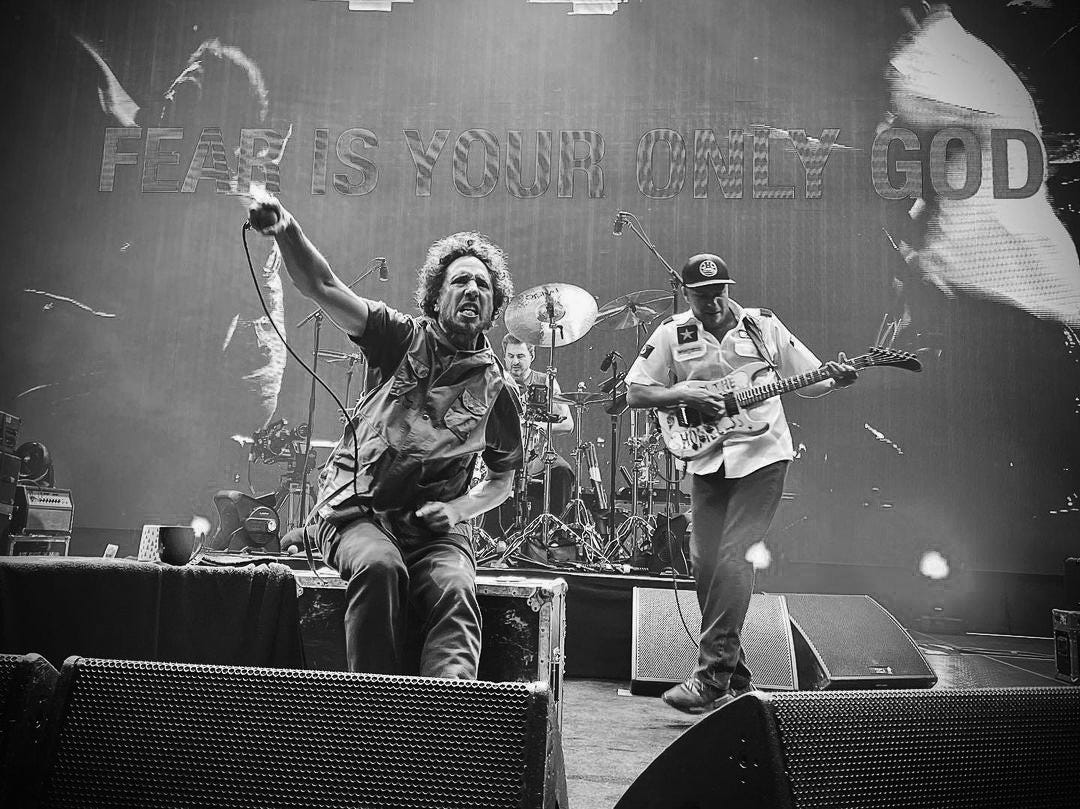

Even if you think you don’t know who Kent McClard is, you know Kent McClard. If you’ve ever credited me with asking anyone about the last time they cried, you should know that Kent did it first in a 1989 interview with Mike Judge for No Answers. If you’ve ever bought a record on Ebullition Records—the influential label whose catalog includes records by Downcast, Orchid, Still Life, Spitboy, Moss Icon, Portraits of Past, Los Crudos, and Reversal of Man, among many others—you should know that Kent has been running that label for almost 35 years now. If you’ve ever read an issue of HeartattaCk, the long-running fanzine that (along with Punk Planet) challenged Maximum Rock’n’Roll for its dominance in the global market, you should know that Kent was its founder and editor. And if you’ve ever even heard of Rage Against the Machine, you should know that Zack de la Rocha borrowed that phrase from a 1990 essay that Kent wrote in No Answers—first as the potential title for the debut Inside Out album, and later, as the name for his new band. Kent’s fingerprints are everywhere.

Despite being one of hardcore’s most historically forward-thinkers, Kent hasn’t actually done all that many interviews. So it felt important to me to give him a platform on this, the first week of Anti-Matter’s first anniversary month, largely because Kent’s work not only inspired me to do a fanzine in the first place, it also inspired the way I think about the culture of hardcore. And almost 40 years after publishing the first issue of No Answers, he is as dedicated to our community as ever. Quite simply, hardcore is his life’s work.

I guess one way to start is by saying I don’t actually know a ton about your life before I discovered No Answers in the late ‘80s, but I believe you grew up in Twin Falls, Idaho. Is that right?

KENT: Yes. I was born in California, but my parents split up when I was two and didn’t get divorced until I was six. My mother was going to law school, but when she got out of law school in 1976, she couldn’t get a job. She only got three offers: One in Alaska, one in Idaho, and one in Hawaii. At the time, Hawaii wasn’t the sort of paradise that we all envision now; it would have been a rough place for a white kid from California to go to school. So we ended up moving to Idaho, and I lived there until 1986—for ten years. The rest of the time, I’ve been in California.

How would you describe growing up in Idaho in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s?

KENT: It was very rural. I basically left the house in the morning and just had to come back in the evening. It was a lot of fishing and rafting. And it was very conservative. I was a loud mouth and had a pretty rough time as a kid. I got beat up a lot. It was harsh. When I was in high school, the rodeo team was actually more popular than the football players. But I was basically a loner. I had very few friends—a couple, but not many.

One thing that I think is kind of important to my evolution is that, when I was in the third grade, my mother took me to buy a winter coat. I bought a yellow coat that day—and that was not a good choice [laughs]. It got called “the piss coat.” And I got called a “faggot” for it. It was one of my very first lessons in what it’s like to be on the outside, and it was all because I bought this yellow coat.

I feel like most people go one of two ways after that scenario, where either they try to undo that memory by becoming the hardest version of themselves or they maybe start developing a little bit of empathy for people who are picked on.

KENT: Yeah. I had no path out of being an outsider. There was no way to get out of that. I did spend a brief time in a very religious [phase], because one of my neighbors was a Bible Baptist preacher, and I was friends with his son, so I went to their church for about six months and got really into it. It was a real thing with people yelling and going up to the front, and I had an actual moment where I thought I “found” Jesus or whatever, and I went up to the front. But that experience ultimately turned me into an atheist because I realized that I didn’t actually find Jesus there. I just needed this community that these people had built, and that had value—especially to someone who was definitely an outsider.

Where does a kid in Idaho find punk rock in 1983?

KENT: I wasn’t even really listening to music. I was just looking for something. I was flipping through this metal magazine and there was a tiny little classified ad for a mailorder—I think it was called Toxic Shock—and I just ordered some stuff. One of the things I ordered was a fanzine pack. It was like five dollars, and they would just send you some random fanzines. So I got Maximum Rock’n’Roll number six or seven. I got Flipside. Ink Disease. And that was it. It was like, This is what I’ve been looking for. This is the place where the weirdos are. My family would go to Chico, California, for Christmas every year, so in December of 1983 I bought a bunch of Crass records—Christ The Album and Penis Envy—and I just consumed all that.

When I was trying to remember something about where you grew up, I googled “Kent McClard Idaho” and the only thing that came up was a newspaper clipping from 1984 that just named everyone in your sophomore high school class who graduated with a 4.0 GPA. I was like, “Yes! Kent is an overachiever, just like me!” [laughs]

KENT: I actually had to take first grade twice. I had some learning disabilities. I didn’t learn how to read. I had very, very bad grades through all of junior high. But punk rock really helped me. It taught me that if you really wanted to succeed and do your own thing, you needed to have power. And education is power. Once I started doing well in school, I could do whatever I wanted and nobody could tell me what to do. So I really envisioned education as a way of freeing yourself, getting out from under the thumb.

The thing is, when I first went to a show, that [sense of] community that I’d felt in that religious experience, it was the same thing. Like, these people were sharing a common feeling without the pretense that it was some kind of religious experience. And to me, that was just amazing. Like, I found this community and I wanted to revel in being an outsider. I got into straight-edge mostly because I didn’t want to be like the people I hated and who hated me, the people who beat me up. My number-one reason for being straight-edge was that I actually wanted to cement the fact that I was a weirdo, that I was going to be different. I’m taking this other path, and it’s fine because we’re all freaks and we’re all crazy and I don’t want to live in this world where there’s all these rules anyway. I’m doing my own thing.

If you started No Answers in 1984, you would have been essentially starting the zine very early in your discovery of punk.

KENT: Yeah. I had never done anything [like that before], but there was no local zine. So I met some kids that were into punk rock, and I got my best friend to help me do No Answers. We started working on it in 1984, but we didn’t tell anyone. I mean, I got a typewriter… I just had to figure out how would you even do this, right? [laughs]. The first issue came out in January or February of 1985, and it generally took about six to eight months to do an issue. I would usually do two a year.

What did you, as a newly-minted punk and high school sophomore, want to accomplish by publishing a fanzine?

KENT: That’s a good question. I think I wanted to change the world. I just wanted to do something that mattered. I mean, if you really get down to it, I took all of this stuff very seriously. I took Crass seriously. I understood that not everybody viewed it that way, but to me this was a revolutionary movement about creating space for people to be different and to not have to be so conformist. I wanted to do my part. I wanted to make a difference. I wanted to build that community that I’d experienced in that church as well, but I wanted to build it on my own terms, without the stuff I didn’t believe in. To me, hardcore was this thing about participation, and No Answers was my way of participating.

Did you move to Goleta [California] for college?

KENT: I did. In 1986.

Was there some sort of punk-related strategy for moving to that location or were you just going to college?

KENT: I wanted to skateboard 24 hours a day, every day of the week, and I never wanted to experience winter ever again. I never wanted to wear pants ever again [laughs]. I got into UCSB, and I moved to Goleta, and there wasn’t a huge punk scene here, but there was a punk scene, and I had to experience being an outsider again. I’d just sort of figured out who I was in high school, but in college it was back to square one, where I’m just this weirdo straight-edge punk kid who skateboards and doesn't fully fit in anywhere. At that point, even straight-edge kids, we were all one community, but we were still different. There wasn’t a straight-edge “scene” yet.

That move would have aligned with Issue 5 of No Answers, where you created this demarcation in the introduction to the zine. You wrote about how you were only going to use No Answers to fulfill your own personal needs from now on—that it was no longer about pleasing anyone else. I don’t know if you remember this.

KENT: I do, vaguely. Because I don’t do anything for other people. I never did No Answers for other people. I never did Ebullition for other people. I’ve done all these things for myself. I’m just trying to reach my own goals and make things that I like, and whatever happens beyond that is out of my control. The vast majority of the world hates what I’ve done in my life, and I don’t care. That’s fine. I always laugh when people are like, “Oh, I really don’t like those records on Ebullition.” I’m like, “Yeah, you and all the other billions of people on the planet.” If that was the point—to make people like it—I wouldn’t have done any of this.

But come on. It’s also nice when people like it.

KENT: You know what? I guess it is. I just actually deal better with criticism. I don’t know how to process praise, really. It makes me feel very uncomfortable. Criticism is a much easier thing to deal with.

It’s just funny because I find myself stopping people in interviews a lot to say something like, “Why do you feel like you need to lessen the value of your work in some way?” Like, you’ve done some amazing things.

KENT: I think it’s because I’ve just always felt like there’s no place in this world for me. I always felt like I didn’t belong. That’s part of it. I still don’t feel like I belong in the world.

Sometimes, when you feel used to a certain reaction, you almost court it.

KENT: I mean, it’s not something I’m trying to run away from… but I don’t know. It’s a good question. I think that, for me, one of the biggest messages I have is: You can do it, too. I really don’t like the idea of “experts.” Like, I understand that there are experts in math and physics and science and all that; I’m not delusional or anti-science [laughs]. But I don’t think anyone’s [average] opinion on stuff is more valuable than anyone else’s. Mine included. So part of that is that I want to explain to people—when I interface with them, and they’re like, “I really like what you do!”—that you can do it, too. You can set your own standards. I’m just a kid doing my thing. I’m not special. I don’t have special powers. I’m just a person that set out to do these things. So some of my rejection [of praise] is saving space for other people not to feel like they can’t also do this.

That became very true when I started doing HeartattaCk. A big part of doing HeartattaCk was about not doing so much quality control that you shut people out. Because the way that people gain experience and get better at things is that they have to do things. And if you only let people who already know how to write and express themselves really well, then you shut everyone else out from trying to learn. I think that’s one of the great things about punk, too, is that it’s not so technical that it locks people out from participation. Participation has value. You don’t necessarily have to be the greatest at everything. You just have to have fun and enjoy yourself and do what you want to do, and who cares about the competition? Who cares about being the best at anything?

That actually resonates with how I received No Answers as a kid. I mean, at the beginning, you were young too, and you were still asking questions like, “What’s your stance on nationalism?” [laughs]. But as the zine progressed I started to get a sense that you were pushing towards self-improvement, or even self-realization. That was No Answers at its peak to me. That’s when it was at its most personal.

KENT: I think it was an ongoing process of the same idea just being refined, and me getting older and having more experiences, and realizing how true some of my core beliefs really were. It just made sense to me and it still does. I still think that the power of the individual is all you have, and I think that’s ultimately what punk and hardcore is about to me. It’s about this kind of individualism, but not individualism at the expense of community.

Hardcore saved my life. It gave me a place. There was a space there that improved my life and gave me something that is the most valuable thing that’s ever happened to me. And I really wanted to make sure that that experience would be available to people in the future. My mission since college has basically been to make sure that hardcore never becomes elitist, that it’s always a place where freaks and outsiders will have a place, if they want it, to try to thrive and find their place. And I think that’s the biggest message of No Answers. It was about trying to secure that space for people, and to encourage people to do their own thing and to find their voice and to have their own experience. That’s what Ebullition was about. That’s what HeartattaCk was about. Everything I’ve ever done is basically to keep hardcore accessible to the masses.

I’ll never forget how, in 1990, on the back cover of an issue of No Answers, you published an essay called “Three Things”—and one of those three things was a short polemic that you started by saying, “I might be gay.” I remember reading that back then and thinking, Damn. That’s bold. You’d talked about queerness before, mostly asking people in bands how they felt about it, but with this essay, you were kind of forcing people to reckon with the possibility that they were already engaging with queerness. You didn’t say you were gay; you just said that you “might be,” and that you were OK with that. That was very powerful for me as a young queer kid. Did something specific inspire that piece?

KENT: I don’t remember specifically what inspired that, but the fact is, we all could be gay. We all could be anything. We’re all just people living our lives, and I don’t know what life is going to be like in the future. Most people don’t. There were just little bits of homophobia popping up [at the time], and I just felt like the best way to fight that was to say I might be gay. I had spent most of my life being called a faggot, and experiencing all those things already, I just couldn’t understand why anyone in the hardcore scene would care about someone being gay. Like, don’t you get it? This is the place where we’re all supposed to be weirdos. And some of the greatest bands, like the Dicks or the Big Boys, there were always fantastic contributions from gay people in hardcore. At what point do you wake up and think that this isn’t a place where gay people should have fun just like anyone else? It was just so clear to me. So I felt like the best way to defeat that kind of homophobia was to basically personalize it—and that’s what came out. It was an honest thing.

I think that was also the same issue where you wrote the “Revolution/Revulsion” essay, which famously coined the phrase “Rage Against the Machine.” As a writer, I know that when I write certain things, they might be received by the world in ways that I have no control over. Obviously, “rage against the machine” was something you wrote and lost control of, and it’s especially interesting to see how it almost belongs to the world in a completely different context than the essay it came from. I know you were originally talking with Inside Out about putting out a record that they wanted to call Rage Against the Machine, but then they signed to Revelation and Zack [de la Rocha] eventually carried the name over to his new band. When was the last time you talked to Zack?

KENT: Man, I don’t know. I mean, it was weird. We were really going to do the [Inside Out] record, and he was going to come up and visit, and we were going to start working on some stuff, and then I never talked to him again [laughs]. I might have seen him at a show or something and said a word or two, but all communication just kind of ended—at some point between the time that I wrote that and when they decided they weren’t going to do it.

Do you remember the first time you became aware of Rage Against the Machine, the band?

KENT: I do. They sent me a box of their demo cassettes. But when it first came up, it didn’t have the same context, right? Like, it definitely got stranger and stranger as time went on. I’m of two minds about it. On one hand, I do feel like they probably achieved something. But at the same time, I don’t know if their message really got through. And I especially felt that way when I saw the Speaker of the House who said Rage Against the Machine was his favorite band. I don’t know if it’s possible to really get ideas across at that level. I mean, it’s clear that their intentions are good, but it’s so ironic because that whole essay is about not being a cog in this machine. It’s just so bizarre that it all played out in the way that it did. It feels like I somehow came back from the future to write that thing.

It’s also worth revisiting the fact that Ebullition was such a touchstone for what I called “the big message” movement of the ‘90s. That first Downcast album specifically was really the beginning of that “fuck a lyric sheet, we’re going to write a lyric book” mini-trend.

KENT: Which was me revisiting Crass. That was basically me wanting to do something like Christ The Album—a combination of literary [arts] and music, or a zine and music. So it’s funny to me because that was such a throwback to early punk and hardcore stuff from the past, but I don’t think everybody had the same context. The whole point of those early Ebullition releases was just to replicate stuff that I really appreciated as a kid—which was basically Crass, Crucifix, and the P.E.A.C.E. compilation. Those records were so important to me as a kid and I wanted to create that same kind of experience for people to come after me.

I will say this, though. I don’t think everything has to be that way. The problem with some of the stuff that happened in the ‘90s is that too many people thought, “Oh. I also have to do that!” But no. You don’t. You can do something else. There was too much following. And that wasn’t the point. Not everything has to be like this. That Downcast record was really great, but did I want every record in the future to be exactly like that? No. I also think there were repercussions. I’d sometimes see these bands that were in high school trying to achieve the same kind of stuff that we did—and they weren’t ready to do that. I once wrote some stuff about how if you’re in high school, I don’t want to hear about global politics. I want to hear about what’s going on with you and the struggles you’re dealing with in life. This should be about you. That was probably the only downside to that stuff.

The other connection we have is that we both started new fanzines—me with Anti-Matter, and you with HeartattaCk—in response to Maximum Rock’n’Roll’s now-infamous “we will decide what is or isn’t punk” editorial policy, which was kind of a big deal at the time.

KENT: That was a very big deal. And the biggest problem about it was that it wasn’t about the ideas. It was about the sound. Who gives a fuck about the sound? And it was totally not true! Like, punk rock has never had a codified sound. Beware the Savage Jaw by Code of Honor is one of my favorite records of all time. Does it sound like any other hardcore band? No! So what the fuck were they talking about? It was like, fuck, have you never heard the Butthole Surfers? It just didn’t make any sense. It was just delusional. It was revisionist almost. I would have been fine if they were narrowing it down to ideas, but they weren’t. It was about the music. Hardcore should sound like whatever hardcore kids want their music to sound like. To me, if you want to go and play your music to a bunch of hardcore kids at a hardcore show, then you’re a hardcore band. If that’s the community that you want to make your music for, then you’re a hardcore band. I don’t care what you sound like. Operation Ivy? Hardcore band. That was the community they chose to play to. This is about the community. That was always my position.

I actually talked to [MRR Founder] Tim [Yohannon] about it. I had a long conversation with him and it was insane. I really couldn’t understand it. He literally told me that he could listen to the first ten seconds of a record and tell whether or not it was a hardcore record. And I was just like, “You’re an idiot” [laughs]. That is the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard a person say in my entire life. Like, I can’t believe you said this stupid thing. It makes no sense at all.

It’s interesting because even though we were both activated by that event, we still took different paths. Like, I was less bothered by the major label thing, but HeartattaCk took a hardline against it. You were also a part of that movement against records with UPC codes, which I thought was really interesting because I had a lot of friends with independent labels who just weren’t bothered by that at all. They were like, “A lot of indie stores use UPCs for inventory and stuff.” It just seemed like a very niche gripe. Why did that become a part of your thinking with the editorial guidelines for HeartattaCk?

KENT: I wanted something that was as objective as possible. UPC codes were objective; there was no subjectivity to it. It was just is there one or isn’t there one? So you can’t make an argument there about bias. Was it perfect? No. But it did its thing. And also, I wasn’t saying that everybody had to do this. It was just what I wanted to do. My biggest problem with what Tim was doing was that it was so biased. It was only based on his personal opinions on how the world should work—but it was done in a way that nobody could understand. There’s no way you can explain it. So I just wanted something that was very cut and dry.

The other thing is that, again, my number-one goal was to protect the community. When hardcore got more successful, I did think that was going to be the end of independent bands. I wanted hardcore to stay accessible. And I just think that when things get too big, there are limits to people’s participation—partly because they see people up on stage and they don’t necessarily think that they could also do that. As the scale gets larger, the difference between an individual person who’s no one and these rock stars gets to be so daunting that people no longer see themselves doing this thing.

But it’s also kind of impossible to close the gate on something. You can’t really control how big you get.

KENT: I just went to those Orchid reunion shows, and there were over a thousand people there. Did I think they were absurdly large? Yes. But you know, I went and I did it. I enjoyed myself. Did I enjoy myself as much as I would have at a smaller place? No [laughs]. But there’s no other way for 7,000 people to see them. Why did 7,000 people want to see them? I don’t understand it. It’s fascinating though. I just don’t really understand why [young] kids would care about old people so much.

There are a lot of ways to think about that question, the first one being that hardcore didn’t have a 40-year history when we were young kids. But I also think a lot about sustainability and continuity. Like, if things don’t grow—if the scene can only stay so big—then how can we keep enough of a lifeline going so that certain things can continue? Or so that your label or your distro can continue? If there are only so many kids in our community, doesn’t that mean you close up shop?

KENT: Yeah, but that’d be OK. It’s not supposed to last forever. Like, if the choice was between closing shop and hardcore losing its accessibility, I would rather close shop. I mean, obviously, that’s not a real choice [laughs]. But if that was the choice I was given, that’s the choice I would make. And you know, it’s not like I’m not completely anti-capitalist; I just like small stuff. I think the scale works better. I think small business works better. I’m just against monopolies and chains. I don’t like too much concentrated power in the hands of a few.

But I don’t know what the answer is. You’re trying to do this difficult dance of being somewhat “successful” and trying to stay independent, and it’s tough. I’m just doing the best I can. I’m just trying to make it up as I go along and making up my own answers. And I’ve made a lot of mistakes. I get people saying to me all the time, “Oh, your barcode thing was stupid.” It wasn’t perfect. But I had to do something, and that was what I went with.

OK, I’ll end with this. In 2010, you wrote something about working on a No Answers anthology book, and unless I missed it, I don’t think that ever came out [laughs]. What happened there?

KENT: I get asked this a lot, and I really appreciate the kind words that people have about No Answers. But to be honest, I don’t know what value No Answers has in the present world. And I don’t think it’s so great that it necessarily needs to exist. Some part of me would like to do it. But some part of me doesn’t have the drive. It’s not something I need to do. It wouldn’t enrich my life. And I feel like doing it might just be feeding my own ego. I’m not sure that’s worth doing.

I also just feel really bad about the past having a stranglehold on the future. Obviously, I know that if I did a No Answers book, it wouldn’t somehow “strangle the future”—like, I’m not delusional about it [laughs]. But I struggle with nostalgia. I would like to do it, I guess. But I would like to change a lot of things probably, too. I don’t know. In the end, I don’t care about my legacy. I just really don’t. This was never about me. I was just a tiny piece of sand in this whole overarching thing.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is CRUCIAL to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

In 1990 No Answers #9 with the Downcast 7” was a life changer. Yeah, I had found the Rev straight edge stuff and the older DC records, but the passion in the sound of that record and level of expression in the writing just clicked. It made me travel to see shows, try to start a band and just rethink my place in the world. Thanks for that Kent. I know I was one of so many that had their lives changed by your work. I know because I’ve met more than a few of them. Still straight edge, still vegan, still questioning…

And having a No Answers book wouldn’t just a look back, it would be a document that could be shared with others inspire them. I know my son would pour through it…

There needs to be a No Answers anthology book. It inspired people like you and me to do fanzines and I’m sure it would still inspire others today.