An Introduction: Part 1

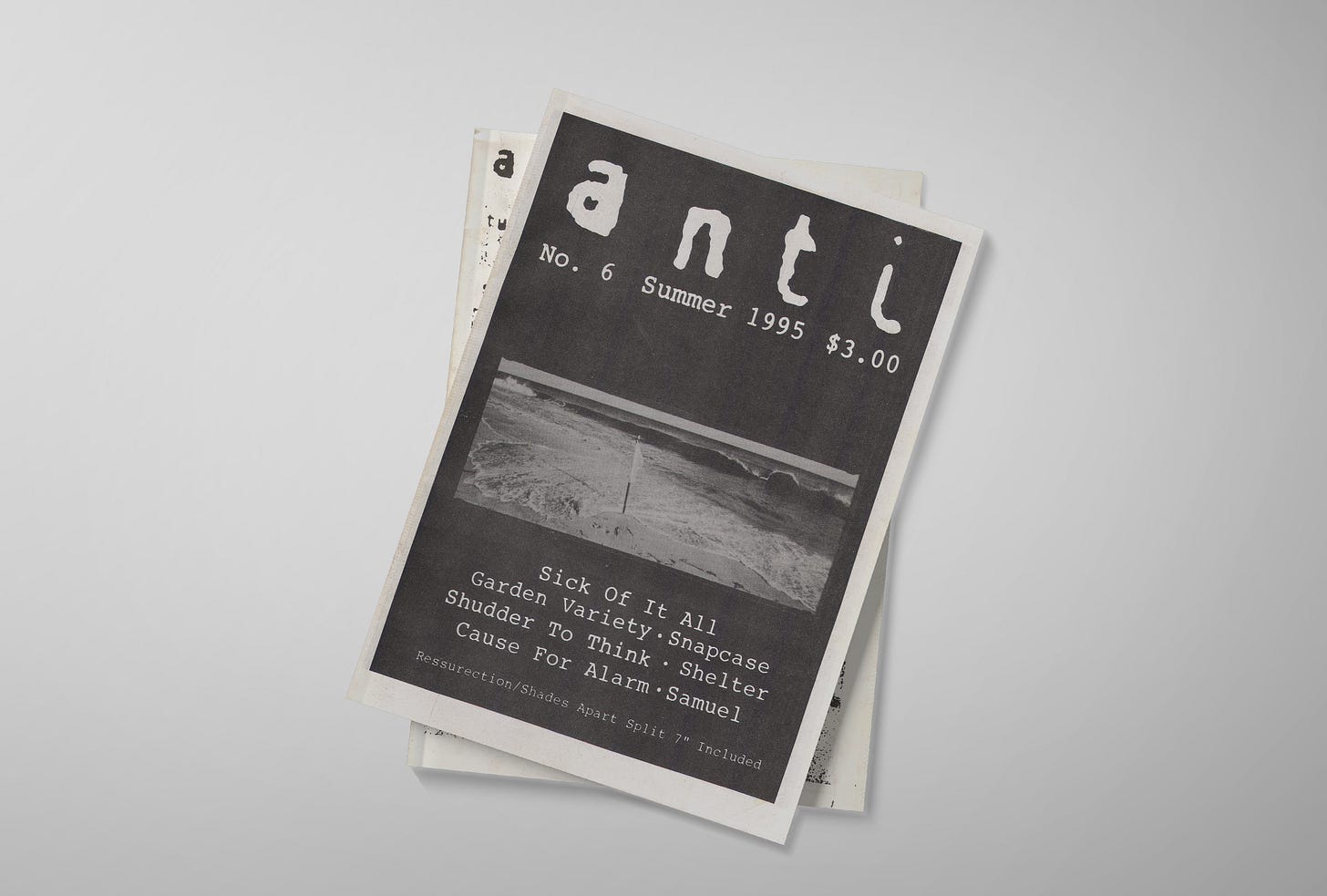

In 1993, I started a hardcore fanzine that tried to make sense of a scene in transition. In Part 1 of 2, I try to explain why I felt Anti-Matter was necessary then—and why it feels relevant again now.

I.

There’s an old aphorism most regularly attributed to Mark Twain that says, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” and in my experience that’s mostly true. If you stay alive long enough, the rhythms get clearer as the distance between points gets wider. Patterns emerge, and if you pay close attention, so too will the words you need to sing along with the new version of that familiar song.

I don’t think about Anti-Matter—the fanzine I started working on exactly thirty years ago this month—as a document of history as much as I consider it a document of memory, and in my mind, there’s a distinction. “Memory” is a deeply individual device, comprised of my experience, my personal taste, my assumptions and biases, and my objectives for doing the work. Put simply, Anti-Matter remembered what I wanted to remember. “History,” on the other hand, is a collective effort, built on consensus and drawn from a variety of primary and secondary sources. It’s no less biased or self-motivated—and history itself can attest to this!—but it is more preoccupied with maintaining a sense of its own legitimacy.

None of that was ever really my thing.

I wasn’t trying to be an archivist, like Ian MacKaye. I never wanted to be a steward of the historical record, like Legs McNeil. I was just a 19-year-old closeted gay hardcore kid, recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder and trying to navigate young manhood as a high-school dropout in New York City with limited resources and no family to fall back on. In more ways than one, Anti-Matter was survival work.

II.

If you really want to introduce Anti-Matter to a new generation—and reacquaint the older ones—then it feels necessary to revisit 1993, the year that conceived Anti-Matter, and the events that compelled its existence into being.

It was the year after Nirvana’s Nevermind sold five million copies in four months and the year before the Offspring’s Smash became the biggest-selling independent album of all time, moving over 11 million units worldwide. In the same month that the first issue of Anti-Matter came out, Green Day entered the studio to record what eventually became Dookie—an album that sold 10 million copies in America alone. The scale of these albums’ success was unprecedented and reality-shifting for everyone in our scene.

It was the year that several legacy punk and hardcore bands—including Flipper, Bad Brains, and Butthole Surfers—went for broke and released their major label debuts, albeit with mostly middling results.

It was also the year that several key late-1980s scene players began seriously exploring the contours of what hardcore could be in a way that both generated excitement and created division within our community. Some of the resulting bands are practically canon now, so many of us don’t realize that.

There was, of course, Quicksand—a supergroup featuring members of Gorilla Biscuits, Beyond, Bold, and Collapse—who brazenly moved left of hardcore’s center by leaning into a more-groove, less-thrash formula practically designed to brush up against the nerves of hardcore purists. They went on to become the standard-bearers for a sound that was eventually dubbed “post-hardcore,” but it didn’t happen on a road already paved: Dozens of hardcore zine reviews at the time snidely dismissed Quicksand as being the turncoat embodiment of “coded messages in slowed-down songs”—to use Walter Schreifels’ own Gorilla Biscuits lyrics against him. And even though they celebrated the release of their major label debut Slip in February of 1993 with a fully sold-out New York City show, we can’t forget that this show also provided a platform for a small, but vocal group of punk protestors who stood outside distributing flyers that criticized the band for their so-called “polished sound” and major-label affiliation.

There was Zack de la Rocha, a former member of Hard Stance and Inside Out, who began experiencing huge commercial success with Rage Against the Machine—a band that blended his iconic hardcore vocal with the political fervor of radical predecessors ranging from Gil-Scott Heron to Public Enemy. Zack’s unparalleled activism changed minds—and lives—but that couldn’t spare him from the hardcore scene’s persistent and sometimes vicious criticism for releasing his band’s music through Sony.

Even Shelter—the band I played with from 1992 to 1994, alongside straightedge legends Ray Cappo and Porcell from Youth of Today—met with multiple protests while on tour that summer. Considering punk’s historically adversarial relationship with religion, it makes total sense that a group of Hare Krishnas encountered resistance. I’m not so dense as to believe otherwise! But all of these events, as a whole, did make me wonder if the hardcore scene had begun turning in on itself. It was like we were finally being forced to decide who we were and what the fuck it was that we were actually doing, many of us for the first time in our punk lives.

1993 was hardcore’s banner year and its breaking point.

III.

There was something else that happened that year, something I can literally point to as the direct catalyst for both Anti-Matter’s existence and purpose. Maximum Rock’n’Roll, which was by far the biggest and most effective community platform for promoting hardcore and punk music before the internet, responded to the explosion of major label signings and mainstream success with a new set of reactionary edicts for their editorial and advertising policies. There were hardline, but perfectly reasonable rules about rejecting major label bands outright, sure. But there were also vague standards for everyone else that allowed MRR editors an arbitrary latitude to decide for themselves what was or wasn’t “punk.” The implications were clear: “Punk traditionalism,” whatever they decided that meant, would be favored over bands that weren’t exactly sticking to their hyper-orthodox script.

Labels run by friends of mine—counting Equal Vision, Revelation, Doghouse, and Victory among them—immediately began worrying about their impending loss of visibility and global reach, and more specifically, how catastrophic it would be for their artists. Even Ian MacKaye’s iconic Dischord Records—quite arguably the most ethical punk label in our scene—felt like their number would be called, too

“I’d say that for years our most successful advertising has been in Maximum Rock’n’Roll,” MacKaye told me in an interview for the second issue of Anti-Matter. “I’m also not sure how much longer we’ll be running our ads with them because of their new policy. I assume it’ll only be a matter of time before they decide not to run our ads because they think that we don’t fall into their narrow definitions.”

All these things together resembled a crisis to me—a threat to the community I treated as my only family in the world—and if being a hardcore kid teaches you anything it’s that you have power. If you don’t like the scene you’re in, you can put on the shows you want to see. If you don’t like the bands on the bill, you can start the band you want to hear. If you don’t like the massive and monopolizing fanzine playing Punk God, you can sit in your bedroom, dream up an alternative, and put it in people’s hands within two months. That’s the thing I chose to do. And by September of 1993, Anti-Matter was real.

Anti-Matter became an almost immediate home for the labels and bands left homeless in the MRR diaspora, and within a year, the zine was selling 5,000 copies per issue—only a fraction of MRR’s 30,000-count circulation, but an insane amount of copies for a hardcore fanzine at the time nonetheless. Over the next several years, it spawned a Punk Planet column, a compilation album, and a book. For whatever reason, Anti-Matter appeared to fill a void. And I loved doing it.

IV.

So how does this all “rhyme” with our present moment in 2023?

For one thing, hardcore is quite possibly the biggest it has ever been. Not punk, not pop punk, but hardcore. Following the astounding success of Turnstile—who, it should be noted, both generate excitement and create division—we’ve seen another reality-shifting moment for this scene. Sound & Fury in Los Angeles attracted 5,000 people last year for a festival free of the usual headliners. It was hardcore for hardcore kids, and that was enough.

We’ve also seen the return of major-label interest in this community—and let’s face it, it’s only a matter of time before someone signs again. (Even Sick of it All gave it a shot thirty years ago.) Whether or not “signing to a major label” has the same sting that it did in 1993 is almost besides the point: It’s more that the new generation will be forced to decide for themselves who they are and what the fuck they’re actually doing, just like we were, many of them for the first time in their punk lives.

We’re also already starting to see a musical evolution from some of the scene’s bigger bands. Psychic Dance Routine, the new EP from Scowl, for one, seems to be marching towards some kind of “post-hardcore” for the band’s future. What that will ultimately sound like remains to be seen.

And while we don’t quite have the hardcore-punk media monolith problem that we had with Maximum Rock’n’Roll, I do believe we are in the middle of a widespread media emergency at large. Only a select handful of hardcore zines, podcasts, and websites seem to be running truly sustainable models right now, and that’s a long-term problem for all of us. Nurturing a healthy punk media ecosystem where a group of stable, dependable, and diverse voices can thrive and evolve with the community they cover is absolutely necessary for a stable, dependable, and diverse hardcore future. The most popular media models that rely largely on social media engagement and ad impressions are simply not poised for long-term success: Vice Media—valued at $5.7 billion in 2017 and acquired out of bankruptcy for $350 million last month—is maybe the most dramatic, but instructive example of this colossal failure of a business plan.

The biggest difference between then and now, for me, is that this idea of relaunching Anti-Matter—in a new medium, for a new era—is not coming from a place of dissatisfaction; it’s coming from a place of inspiration. I’m inspired by the last two years of touring with Thursday, meeting hardcore “kids” whose experiences span all five decades of our community’s history. I’m inspired by the reaction to the series of Anti-Matter interviews I did on Instagram Live during the pandemic in 2020, and how much people really showed up—and showed love—for that. I’m inspired by all the newer bands and by the bands who kept going, riding with the ebbs and flows of public favor. I’m also still inspired by the original mission of Anti-Matter: to create a place to facilitate real conversations with hardcore people, to find the connective tissue between seemingly disparate styles and generations of hardcore and keep us tied together, and to ensure that this scene continues to see the value in creating and maintaining a truly inclusive community that looks out for our own.

And with your help, I’m inspired by the idea of doing this thing right here: producing what I hope will become a long-running, meaningful, reader-supported publication for today’s hardcore community. I’ve always taken Anti-Matter’s legacy very personally, and I am making a huge commitment—and taking a real risk—to make this project a reality in 2023. (There are more announcements on the way!) But I’ll expand on this more in the second part of this introduction, which will detail what you can expect to read here, among other things. That will hit your inbox on Thursday if you subscribe now.

In the meantime, I encourage you to share this letter with anyone who might be interested. Follow Anti-Matter on Instagram. Or find me on Twitter or Threads. More details will be forthcoming, but for now, I offer you my sincere gratitude for reading.

Thank you, friends. x

Norman

I’m sitting on my front porch stoned and listening to samiam and finding this just put a huge smile on my face. I was recently diagnosed with cancer and life has been so up and down of late, it’s nice to have a moment like this where at least for tonight, right now, I’m in 1994 all over again and the world seems alright .

Much love to you on this effort, excited to see what is to come!