An Introduction: Part 2

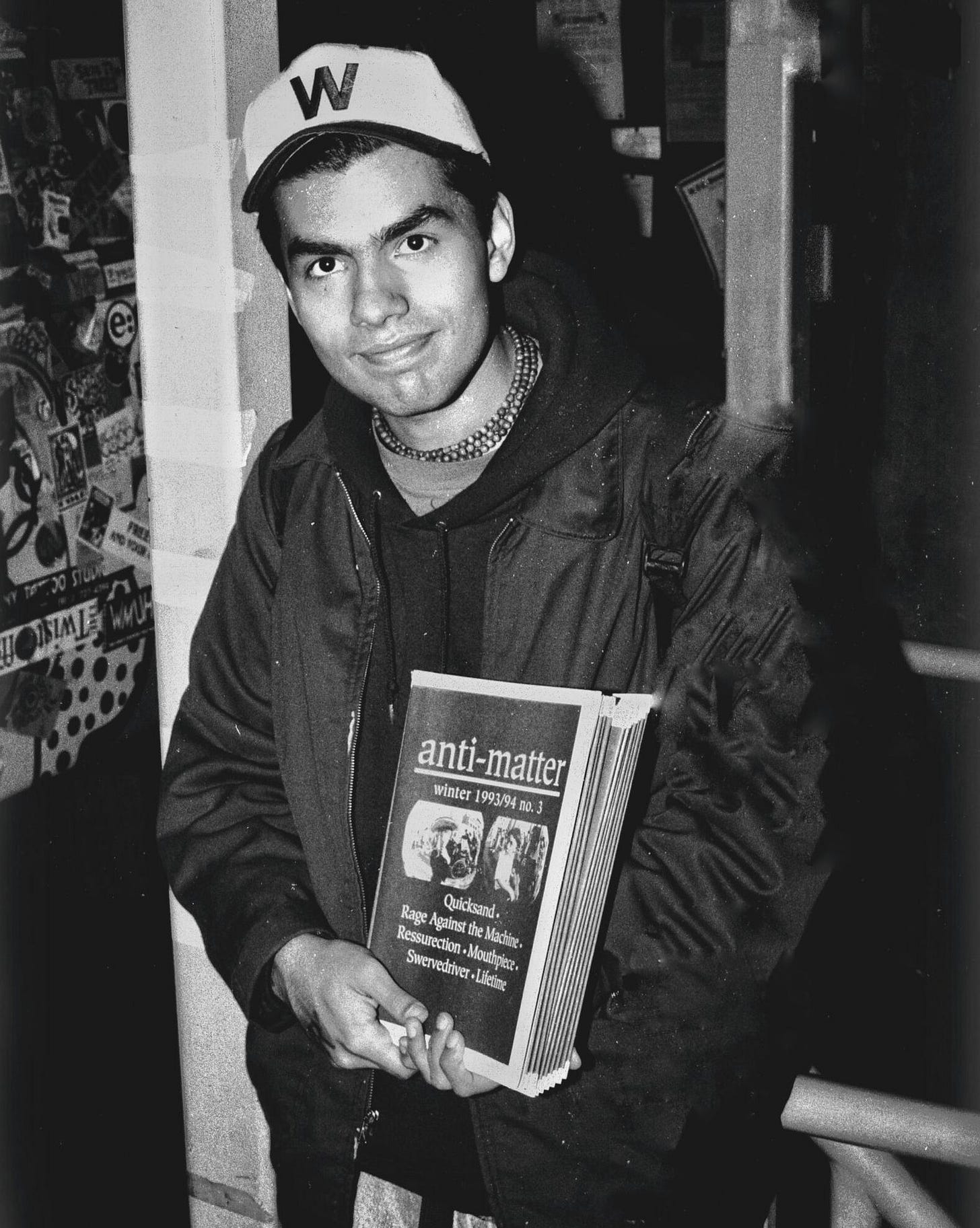

On the eve of a total relaunch, in Part 2 of 2, I attempt to situate Anti-Matter into the present moment by remembering its original ethos and unspoken mission—while also looking towards the future.

I.

In the first part of this introduction I mentioned something about hardcore inflection points—those moments of extreme pressure on the scene “when you are forced to decide who you are and what the fuck it is that you are actually doing.” What I didn’t really get into is how I decided to resolve some of those issues for myself back then, and how some of those ideas are still built into what I’m trying to do now.

In 1993, I knew there were questions about Anti-Matter that I needed to answer first and foremost. Like, how did I really feel about almost everyone I knew signing with a major label? How did I feel about the wide range of music being played under the banner of “hardcore” that seemed to be drifting further and further away from the thrash-and-burn energy of Agnostic Front or Youth Of Today? And how did I feel about advertising in a fanzine? Was it possible to create a model for Anti-Matter that didn’t involve me spending every cent I had without it?

In regards to the major label question at least, I think it’s clear that I chose to err on the side of loyalty to those people whose contributions to the hardcore punk scene felt unimpeachable to me. Every issue of Anti-Matter featured one artist or another who had made the jump; bands like Quicksand, Jawbox, Rage Against the Machine, Sick of it All, and Shudder to Think immediately come to mind. I was occasionally criticized for this position back then, and honestly, I get it. But the more I scrutinized the ways in which I, myself, had been personally exposed to punk, the more it felt like a blanket major-label blackout was inconsistent with my experience. For one thing, the first punk album I ever owned and truly adored was Rocket to Russia by the Ramones—released through Sire Records and distributed by Warner Bros. If it weren’t for the Ramones, I arguably wouldn’t be here, and it felt like a jerk move for me to pompously walk through the door they opened only to lock it behind me.

More than that, though, I had personal relationships with a lot of the bands who signed major label deals in the early- to mid-’90s, and I knew that, for many of them, this was a survival strategy—not a get-rich-quick scheme. As someone struggling to get by on ten dollars an hour working at a health food store in the East Village, I didn’t have a desire to judge. When Chaka Malik—a coworker of mine at the health food store—quit his job to do Orange 9mm full-time after signing with EastWest, the only thought I really had was, I’m happy for my friends.

II.

The “major label question” is somewhat less pressing today, largely because the majority of kids in the scene clearly came to hardcore through some version of major label punk—from Nirvana to Green Day to Blink-182 to Fall Out Boy to My Chemical Romance and so on. The reason Dan Ozzi was able to get so many millennium punk and emo bands to participate in a book called Sellout is partially because that term is basically toothless at this point. Which is why I’d rather get back to that thing about walking through a door only to lock it behind you.

In 2023, as it was in 1993, we still find ourselves confronted with judgment from the self-appointed gatekeepers—people who have decided that there is one singular version of “hardcore” that is more readily defined by allegiance to a musical style than to, what I would call, a hardcore way of being. In my mind, this kind of contemporary gatekeeping is really no different than the arbitrary tribunals of the Maximum Rock’n’Roll editorial staff that catalyzed the first iteration of Anti-Matter. I thought it was bullshit then, and I will continue to act on the conviction that it’s bullshit now.

Because what does hardcore actually sound like?

Forget the ‘90s for a minute and go back further. Do the Stimulators really sound like SS Decontrol? Is Bad Brains not hardcore because they played reggae? (And in fact, I’ve been to Bad Brains shows where they would go off and play 20 minutes of pure reggae in the middle of their set.) Was Reagan Youth not hardcore because they don’t sound like Cro-Mags? Is Cro-Mags not hardcore because they are more metal than the Necros? Is 7 Seconds not hardcore because Kevin Seconds doesn’t technically scream? Seriously, I could do this all day.

You could argue that there are hallmarks of so-called “hardcore music” that define the genre: breakneck speeds, mosh parts, guttural screams, pissed-off lyrics. But there are very few bands from then or now who fit those constricts all the time—if they do at all. From my perspective, this is a severely impoverished vision of what hardcore is and what hardcore could be. My position, and the position of Anti-Matter, has always been a simple one: Hardcore is more than music.

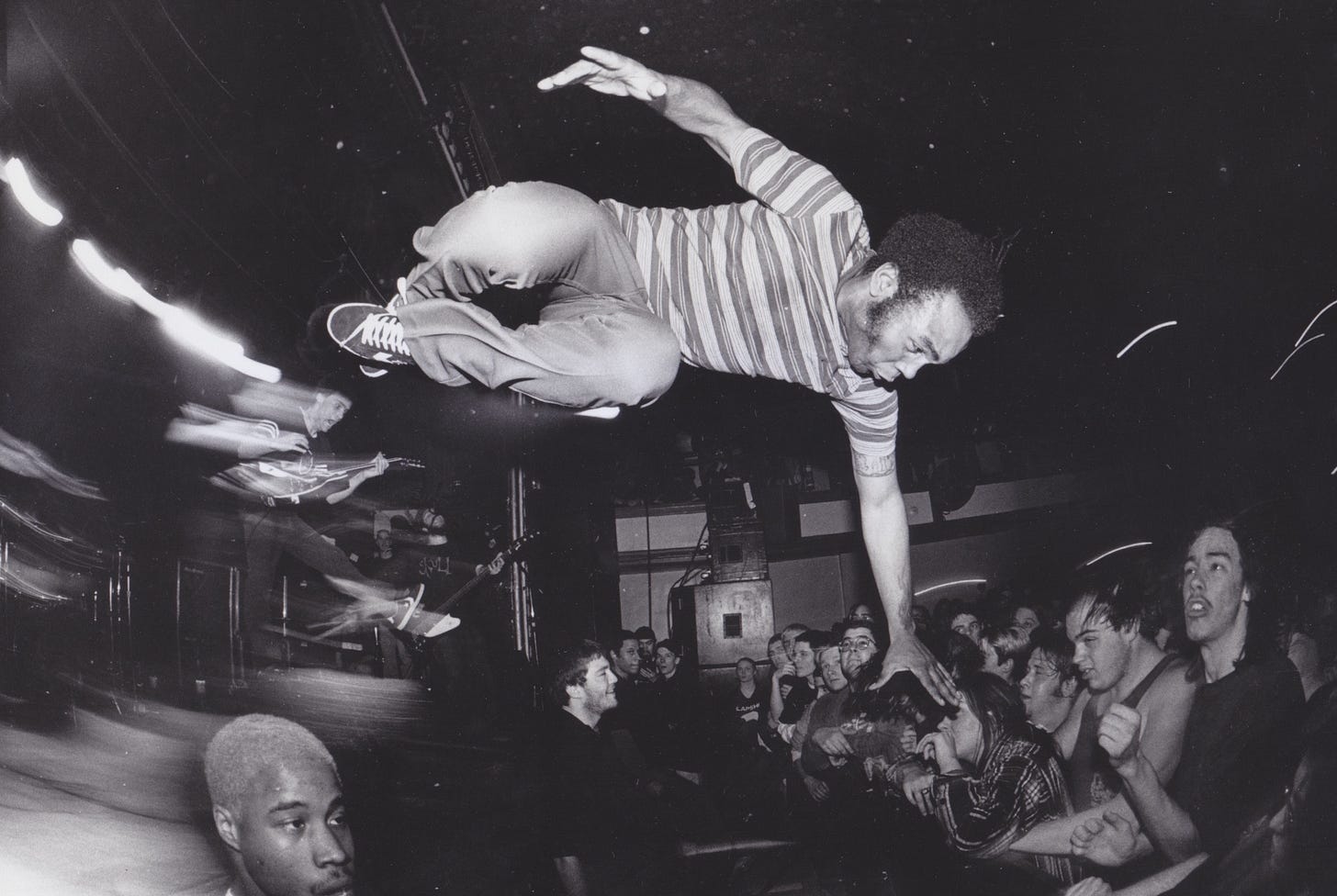

Hardcore is me spending my entire adolescence on the Bowery in Manhattan, risking the trip to a violent neighborhood to find my tribe and feel at peace. Hardcore is starving myself at school so I could use my lunch money to buy records or pay five dollars for the matinee or buy a t-shirt from the band that everyone walked out on because I wanted them to feel like somebody listened. (A true story, by the way.) Hardcore is being a teenaged asshole and still having friends who gave you the benefit of the doubt because we were all fucked up in our own ways. Hardcore is growing up and keeping the same friends you met at the shows because you know you may never meet anyone who understands you that intuitively ever again. Hardcore is listening to other styles of music because you feel like it and because being hardcore means you are free. Hardcore is evolving and growing and aging without a roadmap, but centering yourself with the main thing that hardcore taught you: Hardcore is about finding the realest version of yourself.

Sometimes finding the realest version of yourself means experimenting and taking left turns and doing things that are going to confuse other hardcore kids. But when I recognize that, and I see you in the middle of your journey, and I know it’s coming from a real place, then I’m going to support you because that’s what hardcore kids do.

The other day my friend Sunny Singh at Hate5Six posted a clip to Instagram from Thursday’s headlining set at This is Hardcore last year, and I was so thrilled to see it. I had such an incredible time that day, connecting with old and new friends, watching some amazing bands, and playing that set—the entirety of Full Collapse—for the kids who, we felt, understand it most. Then I saw this exchange in the comments, laughed, and knew it would be immediately relevant to the point I’m making here:

And that is exactly it. There will be no fucking genre cops at Anti-Matter.

III.

The decision to create a space within Anti-Matter for advertising, in the end, wasn’t a difficult one. One of the primary reasons I knew a zine like mine could be viable in 1993 was because MRR created a void that left literally dozens of record labels and punk distros lost at sea. Even so, I tried my best to approach this question ethically: I asked Al Quint—who ran the long-running and well-respected zine Suburban Voice—for advice, and he sent me his rate card and circulation info so that I could prorate my prices appropriately. I made sure to create advertising tiers for all budgets, and whenever I could help a truly strapped punk business with a better deal, I did. Even though readers bought fanzines for the ads as much as the interviews back then—it was pre-internet, after all!—I still tried to keep the signal-to-noise ratio at a reasonable level. I used the ad money to produce and print the zine, and then I used the sales revenue to live a meager life while I worked on the next issue. It was, more or less, a sustainable formula for that time. In fact, the only reason I stopped doing Anti-Matter was because I had just started Texas is the Reason and I felt like it could eventually become a conflict of interest. When I think about that decision now, I believe I was wrong.

Media has changed in almost every way since then. Many of the biggest magazines have drastically reduced their publishing schedules or discontinued print completely. Fanzines continue to exist, but the most successful ones need to cultivate a highly active and parallel online presence to do it. Websites and blogs are vying not only for readership, but for advertising and sponsorship to take the edge off server costs and maybe make a little something for their labor—rightfully so. When I spent the early part of this year imagining what Anti-Matter could look like in 2023, I certainly considered all these things.

But then came Substack. It’s not the perfect platform, but it captured a lot of the things that I loved—and solved some of the problems I didn’t love—about doing the fanzine. For one, there is no other middleman, no tangled web of distribution. I can bring this work to you, directly to your inbox, with the press of a button. But more important to me, this platform allows me to establish a model that’s something more akin to that of PBS or the Guardian UK. I want you, the reader, to be able to support my work directly if you have the resources to do so, if you believe it should exist, and if you believe that you are getting value from it. And my hope is that I will do good work and the readers will respond in kind and that the entire hardcore community can benefit from this zine without paywalls. (That’s the dream, anyway. And so far, it feels like the people are showing up to make this a reality.) It’s sort of like playing a basement show and passing around a coffee tin: I’d like to think everyone would want to give a little something to the band, but you’re not going to get kicked out if you need that money to get home. That’s cool, and I’ve been there.

Either way, as this project grows, I have every intention of giving paid subscribers something more for their contributions: Early access and discounts on a merch drop. Preorder access or special editions for upcoming physical releases (that’s as much of a hint as I can give you right now!). Early access for ticketed events should such events ever come to pass. Whatever I can do to say thank you for making this possible.

IV.

Finally, as we roll into our regular publishing schedule next week, what can you come to expect from Anti-Matter?

Barring disaster, you should expect 8-10 updates a month. Each week will loosely revolve around a theme, with essays on Tuesdays exploring an idea and interviews on Thursdays that will continue the thought in some way.

Next week, for example, I will publish a piece called “Young ‘Til I’m Not”—where I try to rethink the ideal of youth in hardcore in a way that challenges the idea of “aging out” and embraces getting older. Then, two days later, I will post the inaugural interview of this iteration of Anti-Matter: a 29-year-reunion interview with Mike Judge, where we discuss what the hell we were thinking the first time we sat down together in 1994, how we’ve adapted with age, and everything that’s happened since then. (I knew that this relaunch was worth doing when Mike folded his hands over his face at one point and said, “Damn it, Norm. You still ask the hardest questions!”) I can’t wait for you to read it.

There will also be an extra two posts a month, occurring every other Sunday. One will be a new music (and buried treasures) update, where I share what I’ve been listening to and what’s exciting me. The other will be a rolling set of special features. The first special feature, which I’m calling Unlikely Sources, will tap public figures who aren’t very well-known for “being hardcore” to choose and discuss three hardcore songs that they felt carried meaning in their lives. You can look for that to debut on July 29.

Until then, thank you again for being an early subscriber, and don’t forget: sharing this news with your friends or social networks is also a hugely helpful form of support at this stage. (Also, today is my birthday and sharing is the best birthday present!) I am indebted to your kindness. Now let’s fucking go.

Thank you, friends. x

Norman

Happy birthday, dude!

This all hit me in the gut, but this part especially "buy a t-shirt from the band that everyone walked out on because I wanted them to feel like somebody listened. "

If I might share one of the things I hold in my core at every show: no matter who I'm there to see, I give every band attention. Maybe not always full, but I'm not going to hold full on conversations, I'm going to listen, I'm going to watch. Because 1) other people might be trying to listen to *their* favorite band and like you said 2) If you're putting yourself out there on stage, I think you deserve to feel like you're being listened to.

Again, I'm just really happy that this digital zine exists.

Solid read. Please let that picture of the comp be foreshadowing.