A Lull in Traffic

The fall of Pitchfork won't directly rattle the hardcore scene, but there's a bigger story here about why so many music media models fail—and it should concern all of us.

I.

Look up. Wherever you’re reading this, you should see something about Anti-Matter being “a reader-supported publication.” In its current form, this is 100 percent true. What fascinates me now, though, is that the original Anti-Matter fanzine in the ‘90s was not exactly that. The lore about how I once “made a living”—and that’s a generous description of it—from publishing a fanzine is also true. But reader support was only one part of the puzzle back then.

Over the years, I’ve been asked a lot: How the hell did you pull that off? The answer was almost always: math. The first thing I did was invest every last cent I had into publishing the first issue. That came to roughly $2,500, which was a lot of money for a nineteen-year-old in 1993. There were no ads in the first issue, so I was counting solely on point-of-sale revenue to recoup and recover. The first issue sold 2,000 copies, and fortunately, I was able to sell the majority of them at the full two-dollar cover price while on tour that year. Another fraction of those zines were sold to distributors (i.e. kids who set up distro tables at shows) at a one-dollar wholesale price; the rest were given away. All in, I probably grossed a little over $3,000 with nothing but reader support. Again, that was not nothing for a kid my age. More importantly, I got myself out of the red and into the black.

By the next year, however, I realized the model had to evolve. Selling 2,000 copies of a fanzine was amazing, but it took a lot of work to do that just to break even. If I wanted Anti-Matter to continue and grow, I knew I’d need to find a way to cover my most basic overhead with it. Coincidentally, and I’ve told this story before, Maximum Rock’n’Roll stopped taking advertising money from any label they deemed “not punk” at that time. So I took this as an opportunity to adopt a hybrid reader/advertising-supported model. One by one, I started calling some of the affected labels and I asked them to give me the ads that MRR wouldn’t run. Revelation, Equal Vision, Doghouse, Epitaph, Victory, Watermark, New Age, and Overkill, among others, were all shut out by the MRR purge, and they all signed on. That’s where the math comes in: I figured that if I could calculate how many ads I needed to sell in order to pay for the entirety of my printing costs—in addition to creating a budget to pay photographers—then any sales revenue, starting with the first zine sold, would be “profit.” Some version of that equation allowed me to “live from doing Anti-Matter” for a couple of years. I felt like I had cracked some kind of code.

Which is to say that while the print version of Anti-Matter was significantly supported by readers, the hybrid reader/advertising-supported model is what really afforded me the opportunity to continue; it was the only way I could create the financial headroom to live and work on the zine. Back in 1994, I did not feel at odds with that reality. Punk and hardcore businesses needed someplace to connect with punk and hardcore kids, and I loved being able to help make those relationships. There was an ad rate for literally every size of business, and whenever a smaller label needed help, I was not above selling ad space for as low as 20 dollars. As long as I continued to do it myself, I felt good about it. As long as Anti-Matter stayed independent, I felt good. But I won’t lie: I published some ads for music I didn’t care about. And I probably wouldn’t have privileged a few releases for space in the record reviews section had it not been for a label’s ad support. (The actual content of the reviews, I’m relieved to say, still ran unaffected.) I cared about the integrity of the zine, but had it kept going, I might have started to worry more about these cracks.

II.

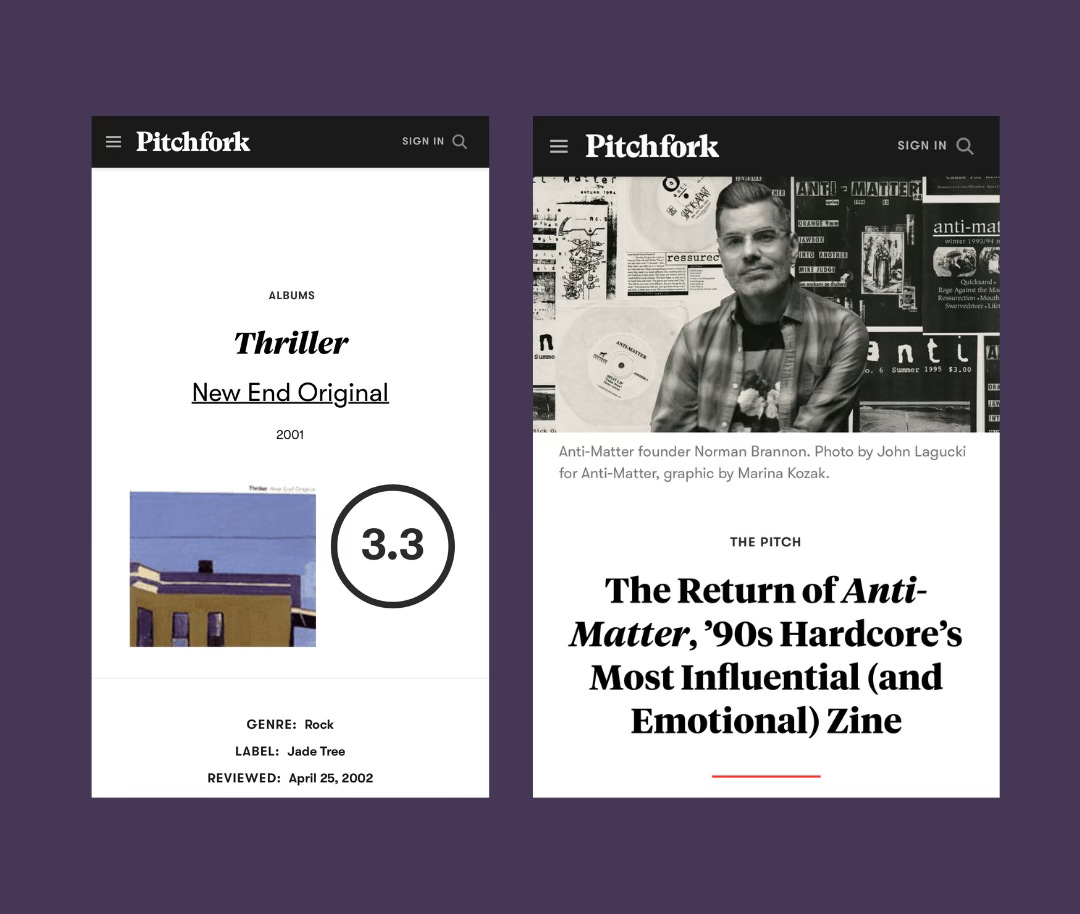

I should begin here with the caveat that my own personal history with Pitchfork is mixed: Twenty-two years ago, a now-uncredited writer for the site declared that I was in “an overtly emotional” band playing “sub-par renditions of whatever Mark Kozelek threw into his dumpster yesterday evening.” But as of three months ago, I have since graduated to becoming the celebrated author of “nineties hardcore’s most influential (and emotional) zine.” History, as they say, is the great equalizer. Even still, when I read the headlines last week—“Condé Nast is Folding Pitchfork Into GQ, With Layoffs”—I approached the story with sadness, not schadenfreude.

I’ve never really been a part of Pitchfork’s key demographic, so even at its cultural peak, the site never held much influence on my musical taste. However, for a long time, I still acknowledged that it was independent and it was good. That a random kid could start a bedroom blog in 1996 and build it out to become the most respected name in music writing is a seriously big deal. Up until their sale to Condé Nast in 2015, Pitchfork was an entirely independent entity; there was never a single outside investor. Whether you agreed with their scope of coverage or not (see: this Triple B Records tweet), a near 20-year run as an indie publisher is an incredible accomplishment by any measure, and even if it wasn’t my beat, I still took that as a personal victory for indie publishers everywhere. In my mind, then, the more distressing headline was the one from nine years ago: “Pitchfork Acquired by Condé Nast.” Last week’s news, in contrast, seemed like it would always come to pass. But that one? That was a surprise.

I don’t know why the creators of Pitchfork felt compelled to make that deal. What I do know is that we live in a culture that propagates (and even fetishizes) the myth of exponential growth, and it’s possible that after 20 years, Pitchfork believed that they, too, could grow exponentially. If that’s the road map you’re following, being acquired by a legacy publisher like Condé Nast might seem like the only way forward. But there’s a wide spectrum of existence between the opposite ends of obscurity and ubiquity, and somewhere in that spectrum is a place where growth is not assumed and “peaking” is OK. Part of that is identifying what makes you special, and holding onto that—even if it’s impossible to scale up.

Let’s not forget that the album review that drove the first major spike of traffic to Pitchfork featured the following sentence: “The butterscotch lamps along the walls of the tight city square bled upward into the cobalt sky, which seemed as strikingly artificial and perfect as a wizard’s cap.” I still don’t know what the fuck that means, but I do know the guy writing it was really trying to connect with this record in a way that legacy publishers will never understand—and readers, in turn, connected with that. Legacy publishers keep fucking up because they can’t accept that people actually want the thing that makes you different.

III.

Anyone who has ever spoken with Ian Shelton from Militarie Gun and Regional Justice Center will tell you: He’s an extremely open person, and although he’ll probably cringe when he reads this, I might even go so far as to say that he’s a softhearted person too, deep down. Our conversation for Anti-Matter, which will appear in full on Thursday, was fairly effortless because we both tend to have higher levels of comfort when talking about uncomfortable things. But over the last few years, as Militarie Gun’s profile has been raised, I’ve noticed that many of the interviews that Ian has been sitting for have felt almost designed to have him share personal details about his life not out of genuine human curiosity or connection, but as a signifier for depth or vulnerability. Some of these interviewers have come off like box-checkers, and it is perceptible. In one such exchange, things got tense.

“There was one interview where it was straight up me and the interviewer kind of arguing for an hour,” Ian recalls. “That one felt terrible because they were basically implying that my traumas were made up for the press. Like, they asked me what the album was about, and then at the end of that block they were like, ‘Is that what it’s really about? Or did you just come up with that at the end for press?’ I was like, ‘What is this combative bullshit?’… I will say, though, with Regional Justice Center, that’s where it starts to feel really bad because people basically go, ‘Hey, tell us that story about why this exists again,’ and that’s when it feels really insulting and terrible. It’s like, you just want me to do my interview that I’ve done for everyone else with you. That doesn’t feel good.”

That’s the other side to any story about publishing models: No matter how much you try to resist it, your model molds the content. Any zine or website that even partially depends on advertising money to exist is going to have to throw its faithful advertisers a bone at some point. Any website that depends on pageviews and unique hits to generate revenue from digital advertising is eventually going to come to the conclusion that sandbagging the singer of Militarie Gun in an interview might be a short-term boon for the click business. And any publication that is acquired by a legacy brand will inevitably submit to the hard financial agenda set by their new publisher—even if by fiat, as we saw with Pitchfork last week.

IV.

There are reasons that I make it a point to let you know that Anti-Matter is “reader-supported.” For one thing, I am not interested in simply collecting as many gawkers and clicks as I can. I am trying to build a model where I can generate trust and relationships with people that I like to call “engaged readers.” Engaged readers are those people who have identified what makes this weekly dispatch special, and who actually come here for that, regardless of whether or not they recognize the names from week to week. Some of my engaged readers, I have since discovered, don’t even identify as “hardcore kids.” That is one of the most exciting developments yet. A recent note that arrived with a paid subscription articulates the sentiment best:

“Hardcore really isn’t even my genre, but everything I have read so far is just really transcendent of genre. I mean, it might help if I knew more about all these bands and scenes, but it is far from necessary. It is all so professional and yet very personal. Great work all around.”

I’ve always considered what I do as a writer to be as much about humanism as it is about hardcore, and this reader was able to glean that from their direct experience with the work. That’s an incredible arbiter for the future. But for as much as I’d love to see exponential growth for Anti-Matter, I know that what I do is niche—and I hold onto that because it’s the thing that makes this different. I live inside of a model where “peaking” is, on some level, an expectation.

The other day I was chatting with a friend about an upcoming career change for him, and somewhere in the conversation, he asked me if there was ever a way that a legacy publisher could convince me that Anti-Matter was a “brand” worth acquiring. I told him the question was moot, really. This has always only ever been a piece of personal expression; it’s not really journalism or documentarian or even archival work. It is simply the way one person experiences the hardcore scene through a very specific set of lenses with which I navigate the world. It will always be only me—it’s me, I am “the thing that makes this different”—and only a finite number of people are ever going to relate to this. So Anti-Matter will grow until it can’t grow anymore, and if I find myself unable to sustain its existence with the reader support I have when the time comes, then it must cease to exist—because there is no other model that will allow me to write about the things I want to write about, in the exact way that I want to write about them, and without any outside interference. That’s the unspoken trade-off of the reader-supported model.

This, too, can be a tightrope to walk. I never said one tightrope is more foolproof than the other, and I truly hope everyone who was affected by the layoffs at Pitchfork land on their feet. But this is the tightrope I have chosen for us, and for now, we are still up in the air.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Ian Shelton of Militarie Gun.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is crucial to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

Thank you for the way that you've chosen to share anti-matter with the world! I decided to subscribe after seeing Thursday in September last year. Pretty sure there was a postcard or something on the merch booth. Anyway, despite growing up in the DC area, and my mother being friends with Ian MacKaye's father, I'm quite new to the ~hardcore scene~ as it were. But I've absolutely loved reading your posts. I've found myself becoming more integrated into the local music scene where I'm at, as opposed to *only* attending big-name stadium shows, and I've had a lot of fun and actually feel connected to the community around me for the first time maybe ever. So thanks for inspiring people and sharing your stories!

"...as much about humanism as it is about hardcore", well said.