What Was I Made For?

We've had countless debates over what "is" or "isn't" hardcore. But maybe it's time to ask: What are we actually trying to accomplish?

I.

There’s an old VICE article from 2016 that I think about from time to time, and its author, Jeremy Allen, clearly penned a title that was designed to be a stick in one’s craw: “Punk Was Rubbish and It Didn’t Change Anything: An Investigation.” Once you get past the title, though, it becomes clearer that Allen’s grievance isn’t directed so much at punk in general, but rather, towards the first wave of British punk: the Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Damned. He contends that this era of punk was somewhat of a broken promise at best, and while some of his assertions are beyond incredulity (the idea that X-Ray Spex “arguably haven’t stood the test of time” is an absurd hill to die on), his primary argument—that “punk’s political influence was relatively minor”—does, on the surface, have some merit.

“Sure, it might have got record companies to finally wake up to a few grotty upstarts doing it for themselves with glue sticks and badge-makers,” Allen writes, “but nothing in the grown-up world changed. The Tories still got elected in 1979, the baby boomers still got rich and fat, and there were still three million unemployed in the ‘80s, even if some of them were singing ‘no future.’”

Where his argument begins to fall short is that, in order for these charges to stick, the reader is forced to make several assumptions about the intentions of these bands—as well as create an arbitrary deadline to evaluate the so-called success or failure of these assumed intentions. To do this, we’d need to actually know: Was punk deliberately conceived to be a catalyst for substantive social and political change outside of the movement? Or did the early punks just see it as an opportunity to forge a parallel society as an alternative to the mainstream culture that expelled us? As for whether or not punk “changed anything,” we’d also need to know exactly how much time our social experiment is allowed to evolve before it’s reasonable to concede, in good faith, that the revolution isn’t coming.

Of course, none of these are answerable questions. For all we know, many of the early punk bands just wanted to ruffle a few feathers, make a few bucks, and then ascribe some sort of meaning to it after the fact. We only have to take their word for it. But these questions are also not particularly relevant today. They say nothing about the 40 years that followed punk’s first wave, and they offer no real insight into the way that we, as punk and hardcore kids, have since then collaborated to create a culture that is meaningful to the way we live now. Even so, we can still use these questions as a springboard to think about our lives and our work in hardcore. After all, we have endlessly debated over what “is” or “isn’t” hardcore over the years. But have we ever truly tried to work out what it is, if anything, that we are trying to accomplish here?

II.

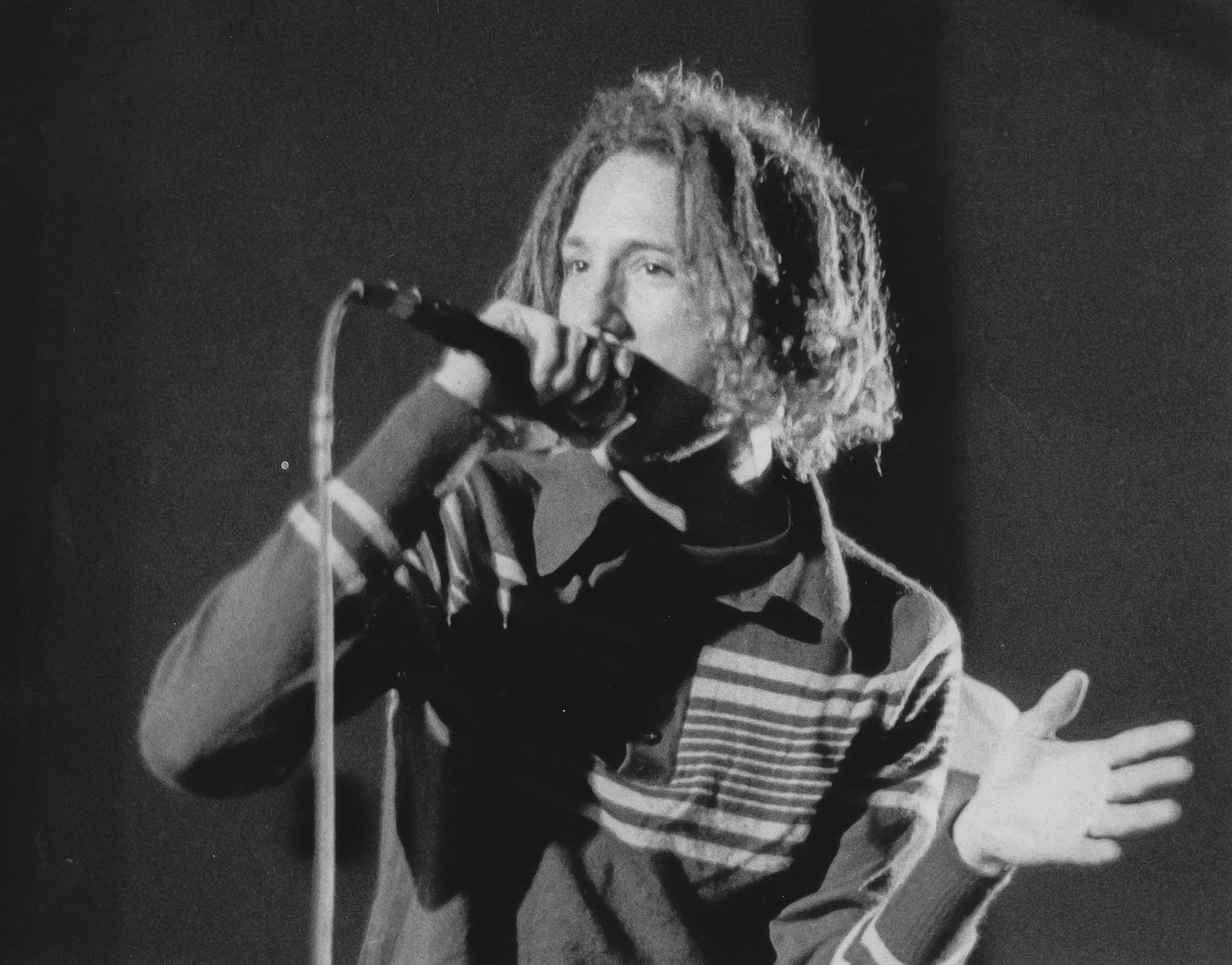

In the Winter 1993 issue of Anti-Matter, Rage Against the Machine’s Zack de la Rocha compared the way we use hardcore to the function of music in early indigenous cultures. “What music was used for back then was to organize, to settle tribal disputes, to communicate and get together spiritually, to uplift and just have that peaceful relationship with the earth,” he said, adding, “Hardcore is stripped of the bullshit. Hardcore is stripped to its purest form.”

What strikes me now as I think about his answer is the way that Zack prioritized community objectives like organizing, reconciliation, and empowerment as embedded functionalities of hardcore—and this is close to how I see it, too. Whenever I speak about hardcore as an ideal, I am speaking about its potential to bring people together, to celebrate our differences, and to give us the space to be (and to celebrate) exactly who we are. That was the promise of hardcore to me as a young kid in the ‘80s, and that’s still the promise I hope to pay forward. In order to do that successfully, though, we have to acknowledge where we fall short. We have to want to get better. And we have to do something about it.

The most obvious advancement that we’ve made over the last 40 years in terms of achieving such community objectives is clearly how far we’ve come in the areas of diversity, visibility, and representation—but it was a slow and hard-won process to get here. This was an issue that I personally struggled with for years.

I often recall the time Nazi skinheads attacked the audience at the very first show I ever played with Fountainhead in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. Forget the fact, just for a moment, that there were enough white power skinheads in 1991 to overtake an entire hardcore festival and just consider the personal calculations I was being forced to make to protect myself in that scenario. I remember thinking: “There are only two people of color in this room—me and Ken Olden from Worlds Collide—and I am not going down.” So when skinheads blocked the exits with two-by-fours in their hands, I made a snap decision to literally jump out of a second-story window and into some bushes to flee the scene. Once the police arrived and the show cleared out, however, I couldn’t believe how many of my friends responded to my escape by making fun of me. I laughed it off in public, but inside I was furious. I knew that anyone who had ever been targeted for the color of their skin before would have related with the very real fear I had for my own safety, but that wasn’t the kind of camaraderie I had access to in the hardcore scene at the time. Having hardcore in common isn’t always enough.

I’m telling you this story now because I did not feel like I had a right to tell this story—in exactly this way—back then. I chose never to share this angle because I wanted to spare other people’s feelings. Because I didn’t want to criticize the scene. Because I didn’t want to be seen as a victim or a buzzkill. But I’m telling it now because I’ve come to appreciate that telling the truth of what happened is not a judgment or a criticism, but an opportunity for introspection and community improvement. I’ve also come to appreciate that I wasn’t being fair to myself: In the hierarchy of feelings I hoped to protect, mine came in dead last.

III.

I hesitate to call Life’s Question a “new” band—on a very technical level, a band by that name with members of the current line-up actually played its first show in 2014—but with the release of a remarkable self-titled EP for Flatspot coming out this week, it certainly feels like they are about to have a moment. For guitarist and co-vocalist Abby Rhine, it’s been a mostly gratifying ride. But as a woman in hardcore, she has also felt compelled to “say out loud what is happening,” as she describes it, and this tendency has been sometimes met with resistance.

“I feel like people get defensive about it because they think, ‘Well, no one is doing this on purpose,’” Abby tells me, for a conversation that will be published in full on Thursday. “But even if you didn’t do it on purpose, it’s like, OK. You still did that. So maybe you should take inventory of why that happened. I don’t want things to be like a checklist of virtue signaling or a checkmark on a diversity box; I don’t want hardcore to reach progress by doing that. But sometimes it feels like someone has to do that for themselves because they are missing it. Like, you could choose to put this in writing or not, but LDB [Fest] this year had no women on the line-up. I mean, that fest is awesome. I totally support that fest. I hear nothing but good things about that fest. But it’s also just true that there were no women on the fest and that’s just weird. It’s an example of how a lot of people didn’t realize that. But it’s just true.”

It’s important to say here that there’s a difference between “call-out culture” and acknowledging a fact to create an awareness or a consciousness that may not be otherwise present for whatever reason. When Nazi skinheads stormed into that venue in 1991, most of my white friends saw a generic threat—a riot not unlike other hardcore riots that we’d seen before. But as one of only two people of color in that room, I felt a heightened and particularly targeted threat. Just because that threat was imperceptible to my friends doesn’t mean it wasn’t real. Still, it was up to me to speak that truth for the community’s benefit, and I failed to do that. The fact that Abby, in 2024, prefaces her comment about LDB Fest by saying “you could choose to put this in writing or not” only goes to show that we both know that—as women, as people of color, as queer people, or as people of other marginalized experiences—there are still risks of being misunderstood or even punished by our community for acknowledging our own imperfections. That simply pointing something out can still be a liability. That for as far as we’ve come on this issue, when it comes to our community objective of empowerment, we are still not quite there yet.

IV.

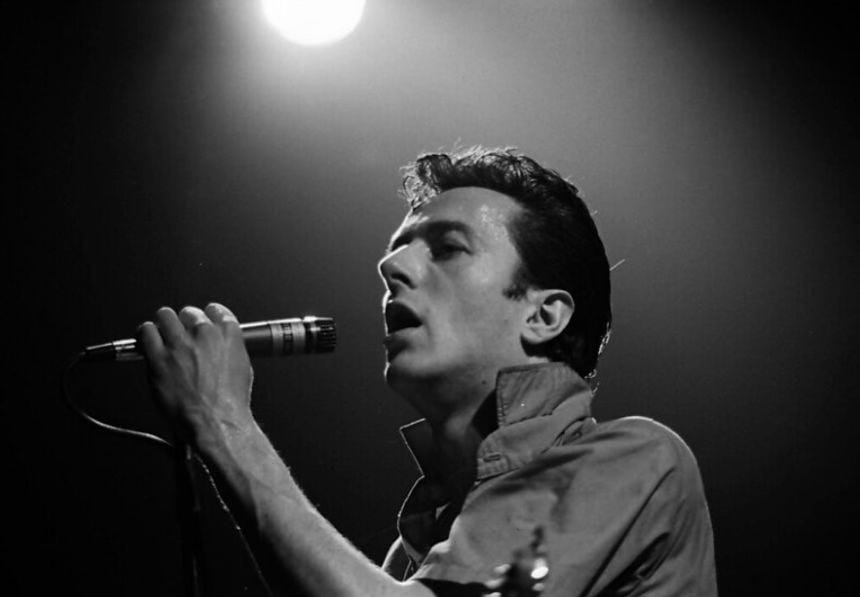

I don’t know what the Sex Pistols’ intentions were. I’ve never spoken to anyone in the Clash or the Damned either, and I have no idea what they thought they were doing in the late 1970s. But if you ask me whether or not I think punk “changed anything,” I can tell you wholeheartedly that I know it did. Because while it didn’t prevent the Tories, or Reagan for that matter, it did have a much longer lasting effect that continues to reverberate in my life.

Punk gave me the confidence to believe that I had something valuable to contribute to the world. Punk gave me a family, and despite our occasional differences, our loyalty to each other has spanned well over three decades by this point. Punk introduced me to vegetarianism, which is something I’ve held dear for 36 years now. Punk gave me a unique point of commonality with my partner of the last eighteen years. It put a guitar in my hand. It took me around the world. It put this zine in front of you. It has practically made my entire life possible.

At the same time, hardcore punk is an ongoing project. We are constantly succeeding and repeatedly failing all the time, but we stay because we believe this community is worth constantly trying to become better people—if for nobody else but each other. To judge our culture based on its failure to make some sort of sweeping gesture to change the face of an entire political system misconstrues our long-term vision, and is arguably missing the point entirely. Because while Johnny Rotten’s early intentions might never be known, other punk pioneers have been more thoughtful and forthright about a kind of personal and social change that begins with our own self-critique. To that end, Ian MacKaye once noted in 1985, “I’m not into political protest, but I do consider my life a protest.”

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Abby Rhine of Life’s Question.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is crucial to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

As always a very thoughtful piece. I really like the line "having hardcore in common isn't always enough." After reading that line I was reminded of the awful year that was 2016 when "The Donald" was elected president and to my horror how many people who were "into punk" loved him. What happened to people's youthful idealism? In a related note about the crumbling of idealism I remember reading in 2019 the New York post's (my guilty pleasure) article about Johnny Rotten's rant directed towards the homeless in L.A. well he was promoting of all things the museum of arts and design's exhibition "to fast to live; too young to die" (I can see now why Deafheaven when they covered Mogwai's song "punk rock" cut out the "sample" of Iggy pop from a 1977 cbc interview praising Johnny rotten that appears in the beginning of the mogwai original.) But as the lyrics in the oasis song "Don't look in anger" said, "Please don't put your life in the hands of a rock and roll band because they will just through it all away."

"Punk gave me the confidence to believe that I had something valuable to contribute to the world... a family... put a guitar in my hand... took me around the world... put this zine in front of you... practically made my entire life possible."

So well said! In my case, Punk also gave me wonderful, real and heavy conversations that my peers in junior high and high school weren't having.