What Price Happiness?

For some, social media provided a platform for hardcore kids to treat each other like soulless ones and zeroes. The joy in hardcore shouldn't be this hard to find.

I.

Before Friendster first launched in 2003, the act of marketing yourself inside of a neatly organized container to be submitted for public audit had been reserved almost exclusively for composing a résumé—a necessary evil, if ever there was one. There is simply no easier way to show your qualifications for work without taking a written inventory of your interests, your skills, and your accomplishments. Still, résumés have a hyperspecific function, and more importantly, they are designed to be expanded upon, in person and with conversation. There has never been a sense that a résumé is a document charged with expressing who you are as much as it is simply meant to show what you’ve done. The most relevant parts of a résumé are objectively measurable; the most relevant qualities of a human, in contrast, are not. We understand this. Or at least we used to.

There were personal ads and bulletin board systems before Friendster, no doubt. There were also early dating sites and niche proto-social networks like Makeoutclub, whose creator, Gibby Miller, went on to become the cofounder of Dais Records—home to High Vis and Trauma Ray, among others. But Friendster was the first social networking site to sweep up folks from almost every social circle I had, or at least enough of them that I felt compelled to join despite my initial resistance to the idea. It was there that I created my first social media “profile” ever, and it was there that I realized I was being asked to define myself with a level of granularity that I never cared to think about before.

Of course, in the years before social media, we were still often tasked with identifying ourselves. We were mainstream or punk, liberal or conservative, theist or atheist, urban or rural. But we also held the luxury of being able to walk around largely blissfully unaware of each other’s every little detail. When I moved to Chicago in 1998 and started DJing in house music clubs, most of my New York friends had no idea what I was doing. Hardcore kids who weren’t in my immediate friend group told me they didn’t hear I’d come out as a gay man until well into the new millennium—years after the fact. At several points in the nineties, I would just take off to India for three months, completely free of any obligation to give anyone an update. There was a freedom to experiment on yourself, and to report back only if and when you felt like it, and it was incredible. What Friendster asked us to do, however, was to make our complex identities byte-sized, and the only way to do that was to reconcile the inevitable contradictions that make up our lives and to update the people around us, frequently, with every minute change to that makeup. Friendster (and later MySpace and Facebook) required us to make choices and take sides, and in doing so, it created an obligation—and a new source of anxiety and discomfort—that did not yet exist.

It may be that you are young enough to have never experienced this exact moment, but if you are old enough to have come of age without the internet—and especially without social media—then it’s quite likely that you, too, remember the first time you were asked to flatten yourself into a single attractive, cohesive, and impossibly consistent avatar of yourself. There was a mass schism and we felt it. It happened at precisely the same moment that we all unwittingly agreed to bear the psychic weight of public scrutiny as a rule, and not an exception.

II.

I will never be the guy who tells you “hardcore was better” at any one particular moment in time. I will never say it because I don’t believe it. But the emergence of the internet—and social networking specifically—have certainly changed the dynamics of how this community talks about each other and even how we talk to each other, and I can’t say it’s been an improvement. Part of this is a symptom of being extremely online: Go on Reddit or inside of the comments section of any band’s social media pages and you’re more than likely to see hardcore kids talking about other hardcore kids as if we were all nothing but flattened avatars. They’ll say things to each other that they’d never say in person at a show, and more often than not, they’ll say it from behind a cloak of anonymity. There can be a lack of empathy involved, for sure, but there is also a distinct lack of joy in these exchanges—and this lack of joy is contagious to everyone who reads it, even if we don’t publicly engage. Because for as much as I say that “I’m not one to click through to the comments,” I almost always do sometimes, and I almost always regret it. If you ever want to feel like hardcore is only a tiny microcosm of the greater world of despair and dehumanization—that same world that many of us came to hardcore to escape—there’s an app for that.

Hardcore joy, I discovered by accident, is offline. But how do I know?

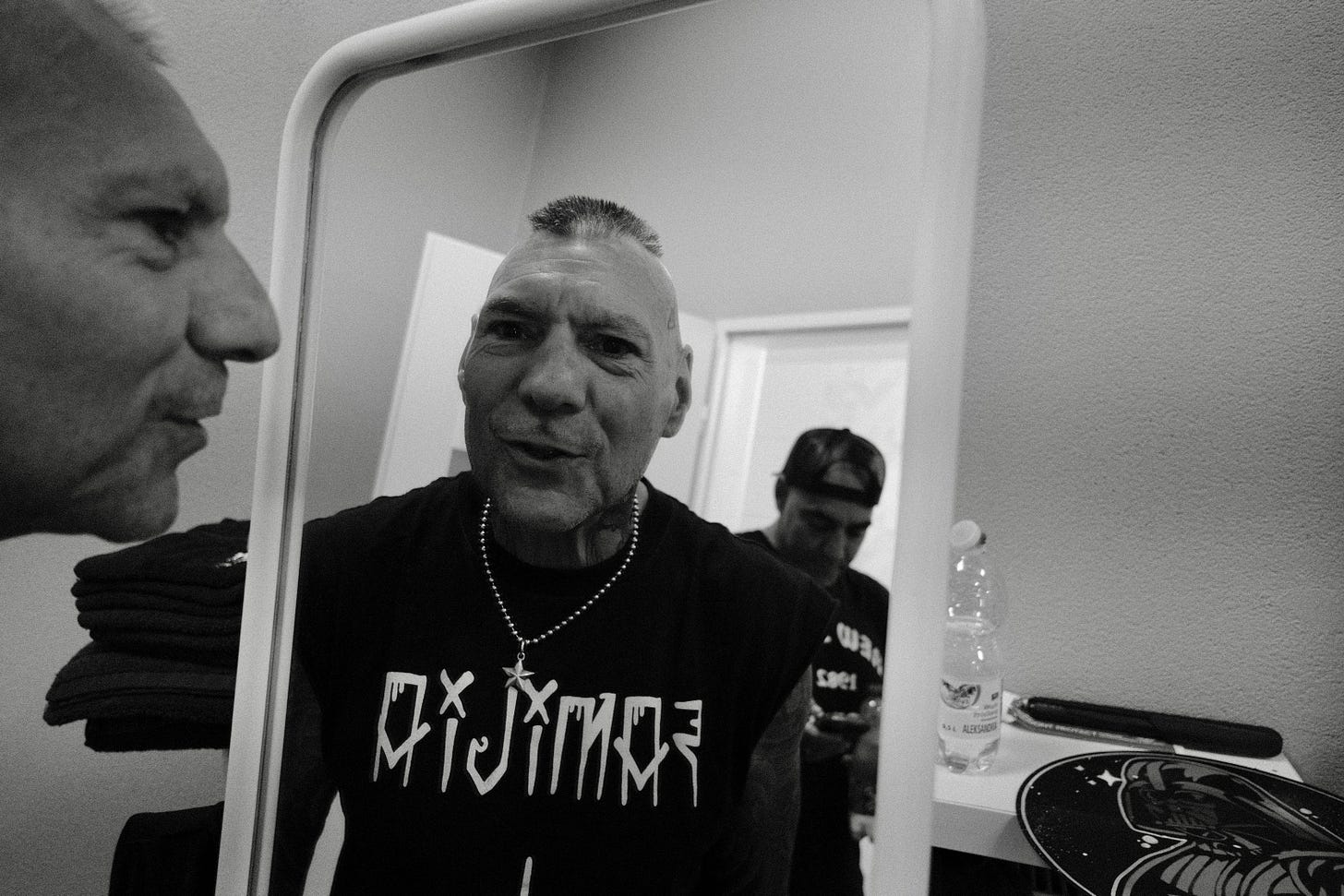

If you speak to almost anyone who has known Vinnie Stigma on a personal level since he founded the legendary Agnostic Front in 1980, you’ll get different versions of the same assertion: This man is not bothered by anything. Stigma’s primary and perhaps only concern, they say, is that everyone gets along. He cares about respect for each other and he cares about community—whether it be the hardcore scene he helped to pioneer or the Lower East Side block where he has lived his entire life—and everything else, goes the assertion, just rolls off his back.

You’ll forgive me if I arrived to my interview with Vinnie Stigma skeptical of this claim, but in 2024, I know very few people who live free from the anxieties of modern life—and even fewer of those people play in bands. If you’re a regular reader of Anti-Matter, in fact, you are probably well-acquainted with many of the anxieties that so many of us contend with in order to do the things we do: the artist-unfriendly economics of streaming, the fear of saying the wrong thing on stage or online to alienate a fanbase, the seemingly never-ending barrage of professional and amateur online criticism, and the pressure of feeling like you must constantly feed the content machine, among several other things. These are all very recent concerns for hardcore bands, but they reflect the reality that hardcore lives as much on the internet as it does in the real world—and the internet, much to our detriment sometimes, is always on. Surely, I thought, Vinnie Stigma cannot be immune to this reality.

Yet the more he and I spoke, the more this assertion came to life. Whenever I attempted to bring up a topic that might have ostensibly bothered almost anyone else, Stigma treated it with all of the fuss of taking a pebble out of his shoe. And whenever he did show genuine worry or concern, it was never about himself. It was about his longtime bandmate (and best friend) Roger Miret’s health challenges or for a fan he met who served in the military during the Iraq War. The bulk of our conversation was, in fact, conspicuously worry-free. “I went to the doctor one day for a checkup and I had perfect blood pressure,” he laughed at one point. “The lady said, ‘I have never seen anybody with such perfect blood pressure.’ And I was like, ‘Yeah. It’s because I don’t give a fuck.’”

The reason for this, as far as I can extrapolate, is because Stigma doesn’t care about things. He cares about people, and throughout our conversation—which will be published in full on Thursday—you can actually sense the almost tangible joy that his relationships bring to his life. Every memory, attached to a person.

“There was a lady, Lily Caggiano, she lived underneath me,” he told me. “I seen her when I was forty-something years old and I was like, ‘Hey Lily, how are you?’ And she said, ‘Hey Vinnie, how are you? You’re such a good boy’—because I used to see her coming up the block and I’d run up to her and grab her groceries. She says, ‘I’m going to church right now. I’m going to light a candle for you.’ I’m not even fucking dead! I’m not dead and they’re lighting candles for me because I show respect. And this is the way I get it back. I live my life like that.”

Whatever cynicism I had going in, I left this conversation convinced that everything I’d ever heard about Vinnie Stigma was true. The only question left, then, was the obvious one: As he approaches his 69th birthday in December, how has Stigma managed to protect himself from the stress and anxiety that keeps the rest of us awake at night? The morning after our conversation I chanced upon something that, I believe, sheds some light on this.

I already knew that Vinnie Stigma doesn’t really do social media; his Instagram presence, for example, is largely mediated by a third party. But what I didn’t know was that he doesn’t even bother to have Wi-Fi at home. Which is to say that Stigma is quite literally as unplugged as you can be in this day and age. He is almost always situated deeply inside of the present, inside of a real-world-with-real-people moment. It defies reason to believe that his nearly carefree way of being is wholly unrelated to this fact.

III.

We often associate hardcore with struggle and strife and anger and even melancholy, but its association with happiness has been somewhat elusive—regardless of the fact that some of my happiest moments have been at a hardcore show, in a puddle of sweat, on stage or singing along to whoever is on stage, huddled together with a group of likeminded people sharing a moment. I know I’m not the only one with this experience.

Bringing Anti-Matter to the internet always felt like a risk to me because I didn’t know how I could avoid the way hardcore music discourse tends to devolve online. I certainly didn’t want to provide another platform for hardcore kids to treat each other like soulless ones and zeroes, and I’m relieved to say that hasn’t happened. But that doesn’t mean I haven’t remained vigilant. Barring a couple of random trolls who came and went, I feel incredibly grateful to have found a community of readers who seem to understand this fanzine’s original premise—which, perhaps not so coincidentally before the internet, hoped to prioritize people over almost everything else. I’ve only ever wanted to unflatten each other, to bring each other as close to three-dimensional as we can using language, and to celebrate our always-evolving selves. To exist on the internet for me, both with this zine and as a person, has always been an uphill battle.

In one of only a handful of hardcore songs I can think of that mentions happiness outright, Youth Brigade’s 1984 song “What Price Happiness” asks a particularly relevant question in this regard. “They say that love’s the only way to find true happiness,” Shawn Stern sings. “So why do we keep fighting for a life that makes no sense?”

In other words, go wherever the love is. That’s where the joy lives.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Vinnie Stigma of Agnostic Front.

Anti-Matter is an ad-free, anti-algorithm, completely reader-supported publication. If you’ve valued reading this and care to ensure its survival, please consider becoming a paid subscriber today. ✨

"To exist on the internet for me, both with this zine and as a person, has always been an uphill battle."

I hear ya and can't imagine what it's like for someone like yourself—with a net cast wider and amplified farther.