True Trans Soul Rebel

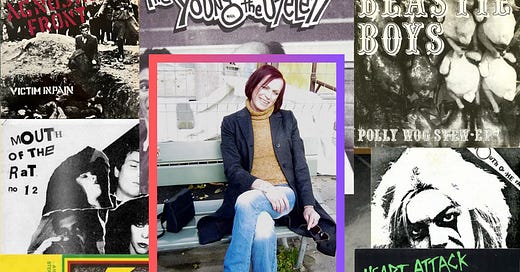

In 1982, she introduced the hardcore scene—and the world—to bands like Agnostic Front and Beastie Boys. Your introduction to Donna Lee Parsons is long overdue.

I.

It was on the front page of her personal website that Donna Lee Parsons chose to begin her story with a short vignette about a boy.

“I sit on the sofa in the parlor and ole Dave Ratcage has just gone out the door,” she wrote. “Moments before, I had told him, ‘You were a wonderful boy, but much as I do so love you, David, we just cannot be. There are things that I must do… without you.’ And so he is walking away down the sidewalk hunched over with that walk of his, looking a little downtrodden. It’s true we had lots of fun together. He would buy me clothes, and he really enjoyed it when I got dressed up for him, and he was so loving and appreciative. I watch him go. Soon he will be out of sight and I must watch him until he disappears around the corner.”

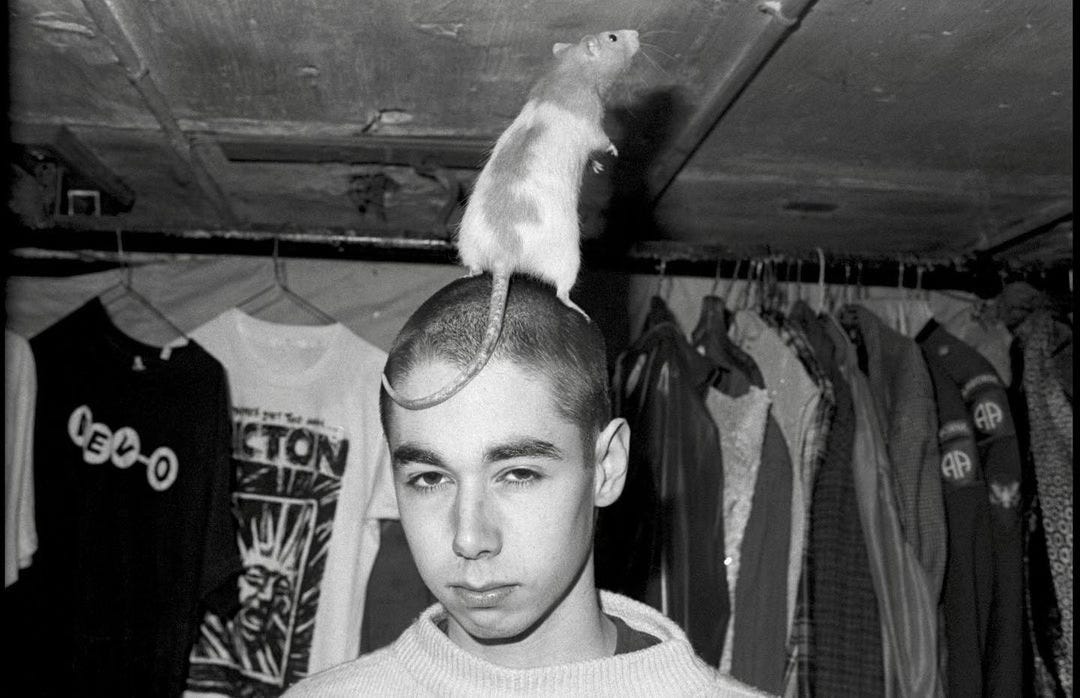

That “wonderful boy,” Dave Parsons, was both a friend and an obstacle to Donna. He was also a consequential figure in hardcore history. Dave started publishing his South Florida punk fanzine, Mouth of the Rat—cheekily named after his hometown of Boca Raton—as early as 1979. By 1981, Dave and his girlfriend Cathy left Florida for New York City where they opened a record store called Rat Cage Records. It quickly became a local hub and a hangout for New York’s emerging hardcore scene. (In a recent Instagram post, the Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan shared a photo of himself “tripping on acid,” laid out on the sidewalk in front of the store.) A year later, Dave saw the need to create a record label to document this burgeoning scene, and Rat Cage expanded to fill that void. Over the next couple of years, Rat Cage released Agnostic Front’s seminal Victim in Pain album, the final Heart Attack EP (featuring a young Jesse Malin), as well as the first two Beastie Boys records, among several others. And if that weren’t enough, Parsons is also responsible for—and almost never credited with—designing the Bad Brains’ iconic “lightning bolt” design, which first appeared on the packaging for their debut ROIR cassette.

“The guy from ROIR supposedly won an award at a design congress for Best Cassette Package, which I designed to the last detail,” Parsons recalled in a 2002 interview. “Even including the idea of alternating green, red, and yellow colored cassettes. If you wanted [them] all, you had to buy three! I never made one cent off that one. But a goal was achieved and I’m very proud of that cover and drawing.”

Simply put, without “Dave Ratcage,” everything we know about hardcore today would be wildly different. Perhaps even unrecognizable. When Donna Lee Parsons wrote that brief eulogy for him in 2002, she didn’t necessarily want you to forget him, but she did want you to know that his time was up. Finally, after so many years, it was her turn.

II.

I’ve often said that the history of LGBTQ+ people in the hardcore scene is like the history of LGBTQ+ people everywhere: We are sometimes hidden and often erased. These days, it seems almost normal to start one’s public life as an out queer or trans person, but for most of recorded history, this was simply not the case. Whether we struggled in private or in front of the world, the outcomes have varied to the extent that there will always be some things we may never know about the people who came before us. That’s because while many of us did eventually come out—as queer, as trans, or in some other way—many of us didn’t. Some of us had “traditional” marriages and kids. Some of us struggled with gender dysphoria our entire lives. Some of us died naturally. Many of us killed ourselves.

As it turns out, Donna Lee Parsons was always hiding in plain sight. Kenny Klein, an older New York fixture who was there, describes Donna as “a brilliant character, who became well known in the East Village scene not only for Mouth of the Rat and Rat Cage Records, but also for wearing his girlfriend’s dresses while recklessly skateboarding along Avenue A, narrowly avoiding drag queen death under the wheels of speeding cars.”

Similarly, in his recent memoir, Agnostic Front’s Roger Miret writes: “When we mastered Victim In Pain at Frankford Wayne, Dave showed up wearing a dress and freaked the shit out of the engineer. We didn’t have any problem with that. Anything goes in New York. Plus, Dave was cool. So what if he liked to wear silky panties and a bra? To each his own.”

This tracks with Donna’s own description of that era. “I was deliberately trying to look like a woman in public,” she wrote on her personal blog in September 2002, “although I still clung to the ‘shock’ element of punk as a protective buffer. I had a very long way to go.”

Part of it, of course, is that Donna didn’t have a language to describe her experience, and in fact, she says that it wasn’t until January of 2002 that she first heard the word “transgender.” As soon as she read about it, Donna saw herself—perhaps for the first time—and began transitioning almost immediately. (“I saw the light at the end of a very dark tunnel and I ran straight for it,” she wrote.) Tragically, not long afterwards, Donna was diagnosed with colon cancer. She had an operation to remove the cancer that year, followed by six months of chemotherapy, but the cancer came back.

“My understanding was that she was pretty much dying, and that she wanted to live out the rest of the little time she had left in the body of her choosing,” recalls Beastie Boys’ Adam Horovitz in Beastie Boys Book. “So [Adam] Yauch took care of it. He organized it so we gave her the money for the [gender-affirming] operation, but it was under the guise of reimbursement and unpaid back royalties for the Polly Wog Stew record from 1982. Donna got the operation, and then within a year passed away.”

Donna Lee Parsons died on September 23, 2003.

III.

When Laura Jane Grace came out as a transgender woman in a Rolling Stone article in May 2012, you would have been hard-pressed to name any other out trans people in punk bands that held the same scale and stature of Against Me! There would be public scrutiny waiting for her, and the potential for high-stakes personal and professional consequences after coming out was very real. But like Donna, Laura saw the light at the end of a very dark tunnel and ran straight for it. In retrospect, she tells me, “I had this ultimate sense of fuck-it abandon where I just didn’t care. I didn’t care what happened because I was at the edge of being like, ‘I want to die.’ So anything after that was almost a bonus.”

As someone who quit my own band in 1997 rather than come out as a gay musician and make an attempt at becoming whole, I watched Laura’s experience play out almost fifteen years later with both envy (for the strength to do it) and concern (for the way becoming a public trans figure almost overnight could affect her). I was elated by the success of Transgender Dysphoria Blues, which incredibly turns ten this year, but I was also curious about how the pressure and attention was affecting her own ability to process coming out, and more importantly, grow into the person she was becoming. One of the greatest misconceptions that people have about coming out is that simply doing so is an end of some sort when, in reality, it’s a humble beginning. As I say to Laura in our conversation, which will be published in full on Thursday, “it’s more like once you do it, you’re staring at a fucking group of broken pieces all around you, trying to put yourself back together, and trying to figure out what was real and what was not real.” For her part, Laura looks back on that moment knowing that she had just reached a place where—for better or for worse—there was simply no other choice.

“Ultimately, I don’t think it’s healthy to come out in the public eye like that. You should not do that, really!” she laughs. “But in a way, it’s almost like sobering up—where you can sober up and you may not be ‘fucked up’ anymore, but you’re still fucked up. And then there’s all this work that needs to be done. One of my therapists told me, very early on, ‘You need to understand that the person you think you’re becoming is not who you’re going to be.’ I think, subconsciously, I realized that before they said it, but that was what’s so ultimately terrifying. I realized that I had no idea what was about to happen, really.”

Fortunately, Laura is still in the middle of her story. She has a new solo record out, called Hole In My Head, and she recently married her partner, Paris Campbell. Coming out didn’t direct the flow of her life as much as it made her life possible.

“To be married now, and to have another shot at that, but to know that you don’t have those things that fucked you up in the past as an issue is pretty fucking awesome,” she tells me, almost joyfully.

IV.

Laura Jane Grace’s legacy in punk history is assured, but it has always bothered me that the legacy of Donna Lee Parsons—both in hardcore and queer history—is still unsettled. The major difference between their stories is stark: Laura came out while she was still a public figure, whereas Donna retreated from the scene in 1986, long before her transition, leaving most of New York’s first-generation hardcore kids with only whatever stories and images that “Dave Ratcage” had left behind. Putting her hardcore story all in one place, the way I hope I did here, is personal to me. If we are to understand where we come from—as hardcore kids and outsiders alike—we cannot allow for only half of Donna’s story be told.

There seems to be a temptation among many of the people who have shared memories about “Dave Ratcage” to speak about Donna as if she isn’t actually the person in those stories—as if, somehow, her pre-transition accomplishments and innovations do not belong to her. But it was, in fact, Donna who founded Rat Cage Records. It was Donna who designed the Bad Brains cassette. It was Donna who had the incredible imagination and foresight to ask Beastie Boys to make a record for Rat Cage at their first show ever. So if you’ve ever worn a “lightning bolt” t-shirt or listened to Victim in Pain or found yourself fondly recalling a Beastie Boys show you went to, you have a transgender woman to thank for that. And we should know her story. If you call yourself a hardcore kid, Donna Lee Parsons touched your life.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Laura Jane Grace.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is crucial to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

Thank you so very much for this essay on Donna. Until the Beasties' book I knew nothing about Rat Cage other than it was a store and it put out the best hardcore record ever. My youngest child is trans masculine and is only just becoming who they are in appearance to reflect who they are mind and soul. I am vwry happy to share this piece with them. They are also digging their dad's hardcore punk records and I think the articke will hit home.

I love all of these essays, don’t get me wrong, but when you write about queerness in hardcore — with reverence and purpose and beauty — I do feel like pieces of myself knit themselves together. All of these facets of ourselves are not only allowed to co-exist, they are often foundational to the things we love most. Thank you for this 💕