In Conversation: Vic Dicara of 108 & Inside Out

In the '90s, Vic DiCara helped set the tone for what became Krishnacore. Since then, he’s had some second thoughts—and a few regrets. But today he feels more like himself than he's ever felt.

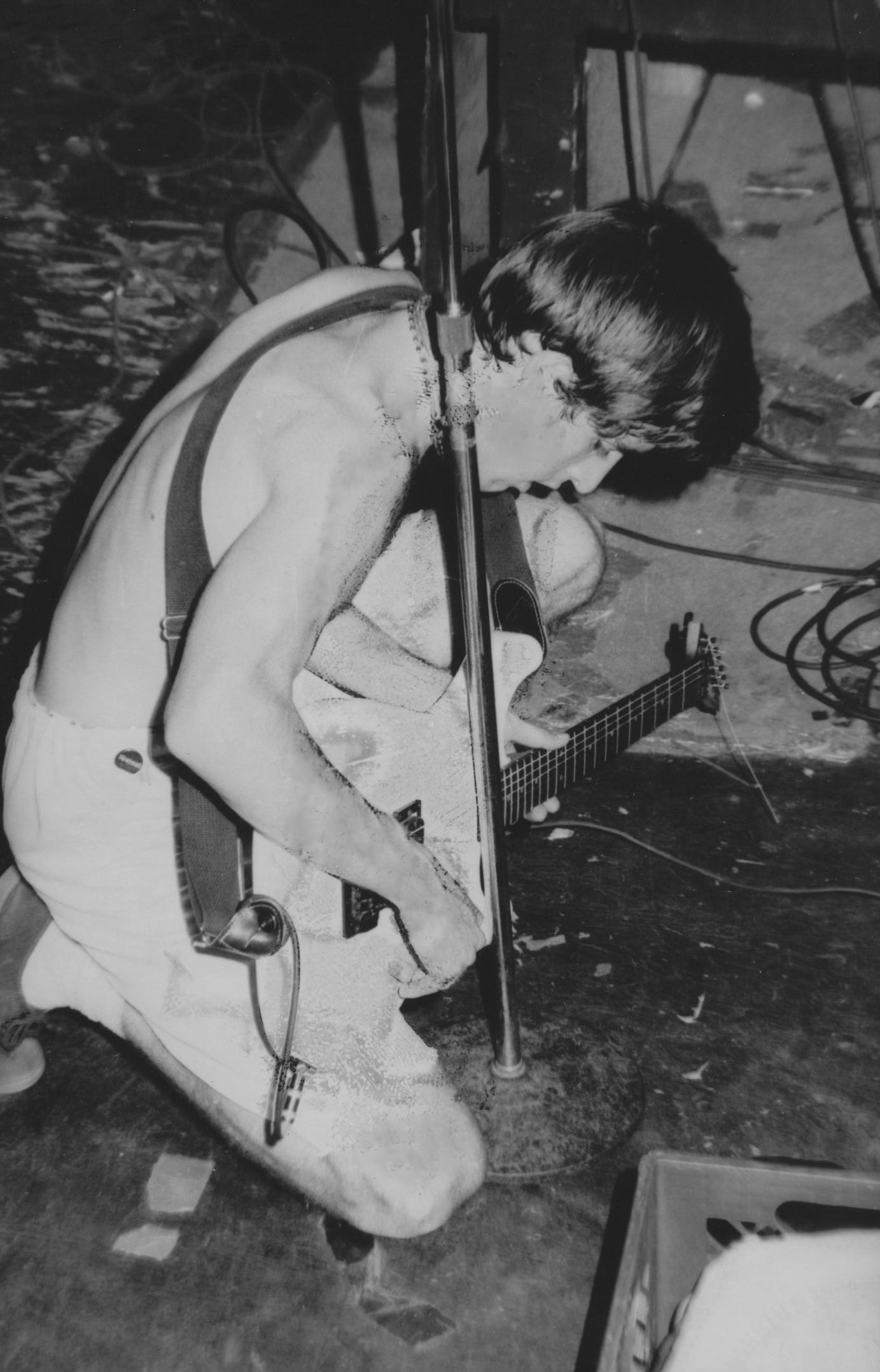

There’s a lot that can be written about Krishnacore’s historical moment in the ‘90s, and although time has rendered most of that moment into a tiny mark, the era will still be remembered as a major part of hundreds of people’s lives—not the least of which includes Vic DiCara, the former Inside Out and Shelter guitarist who went on to form 108 and become one of Krishnacore’s most vocal agents. But after the wave, there was a washout: Vic contentiously left ISKCON, the institutional body best known in the West for being “the Hare Krishnas,” and was forced to rediscover and recreate himself after almost a decade as a monk. These days, Vic lives in Japan and is both a Vedic astrologer and a translator of ancient Sanskrit texts; he hasn’t completely renounced the substance of the tradition he discovered back then. But while he looks back on his role in the Krishnacore movement with some regret today, he’s also finally at peace with his present. It’s a hard-earned calm.

In full disclosure, I’ve known Vic for the better part of the last 34 years, and I actually spent a couple of years playing with both 108 and Shelter between 1992 and 1994. It’s this shared experience with him that I believe makes our conversation so deeply personal. In fact, unlike any interview I’ve ever done before, I came to this one without any agenda or prepared questions. I wanted this to be a conversation that only the two of us could have, and I believe it is.

The first time I ever heard of you was at some point in the ‘80s when I got a copy of Shred Fanzine, which was a zine you did that I’d say was very true to Long Island culture back then—music, skating, BMX. So I think I want to start there. Before Krishna, before Beyond even, where was your mind at?

VIC: It’s hard to start, isn’t it? It’s hard to pick a place to start. But I think let’s start with this: One of the first things I think I knew about myself back then is that I wasn’t a jock—whereas compared to the rest of the kids around me, the boys around me, they were all jocks. So I felt like, “I wonder who I’m going to be friends with?” My alternative to that was that I fell in with these guys that were doing BMX. At first it was dirt-bike, BMX racing, and then after that I got into freestyle and all the tricks. It was kind of a sport, but it wasn’t a jocky kind of sport, you know? It just appealed to me.

At the time, music for me was just what my parents liked—and they liked cool stuff. My parents liked Led Zeppelin, The Doors, some weirder stuff like Tom Waits. So I wasn’t really hungry for anything else. But then I met these skateboarders. And these skateboarders were into punk, so by watching skate videos, I got exposed to Agent Orange and that poppy kind of punk, which I liked. I also think puberty happened. Girls were on my mind, and I thought girls liked musicians and bands, so I thought, “Maybe I could do that”—like that was my in [laughs]. I knew how to play piano because my mom put me in piano lessons, so at first I tried to play synthesizer for this garage band, but they kicked me out. They said, “Why don’t you try to learn the bass?” So my parents bought me a bass for my birthday, but it was this awful Gene Simmons model. It was more embarrassing than good. I was just like, fuck. But my dad had a guitar lying around, and he had a Gorilla amp in his room, so I plugged it in one day and I put on a Metallica record and I just tried to play along. I think it was “The Thing That Should Not Be.” And somehow I could play along with that song! I was like, “God, this is so cool. I know how to play guitar!”

During that time did you feel more like you didn’t fit in or more that you were actually sort of countercultural?

VIC: I felt confused. Like, one of my early memories is just crying for no reason. It’s not typical, I think, to do that [laughs]. Just feeling like all of these people in my grade or in my class, they all had things they wanted to do or places they wanted to go, but I didn’t give a damn about any of that stuff. Like, what motivates me? I don’t know. I don’t know where I fit in. I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. So I think I just kind of fell in with BMX, and that led to falling in with skateboarders, and that led to falling in with the metalhead-crossover-Anthrax-type people that were around Long Island. And that led to winding up in Beyond.

Long Island was really into crossover. Sundance was the crossover capital.

VIC: That was my first place. My first show was at Sundance.

Mine too. What was yours?

VIC: I think it may have been Agnostic Front. Or maybe Corrosion of Conformity.

Mine was Crumbsuckers.

VIC: Crumbsuckers, for me, were like gods.

When you started going to shows there, did you feel a sense of difference in that suburban hardcore experience?

VIC: I guess so. I mean, my first-ever memory of New York City is, again, crying [laughs]. My parents took me to New York City and I started crying because I saw graffiti on the walls and I thought it was the most awful thing in the world. Like, why would somebody do this? Somebody took so much time to make this beautiful building and you just sprayed your name on it. That made me cry! So I sort of knew there was such a thing as a city, but it wasn’t big on my mind that there was a city and I wasn’t in it—at least until I met Tom Capone and Kevin Egan. They took me to CBGB for hardcore shows, so I went to the Bowery instead of going to my parents’ [version of the city on] Broadway. I went to the Bowery and I was like, “Oh shit. This is urban” [laughs]. I didn’t know if I was going to get killed in this corner or what was going to happen, but I liked it.

I think I had the opposite situation, where my parents moved to Long Island and I was like, “Oh my God, what the fuck am I doing here?” There was never a sense of belonging for me there. I knew the city was my place and I went back as soon as I could. Did either of those places feel like “your place” at the time?

VIC: Yeah, that’s the real question for me: Has any place ever really felt like my place? That’s kind of my problem. In hindsight, I understand why traditional cultures put a taboo on traveling or leaving your country—because it actually sucks. Uprooting myself, moving myself all over the world like a million times over, I can see why it’s not good. Because, like, where are my friends? The kids that you go to school with, the kids I was in grade school with, that bond is really deep. And now where are they? I have no idea. Whereas if you stay in one place, you maintain relationships, and I think that’s really healthy. But for me, I don’t have any of those lifelines. Somebody that you could just talk to or hang out with and they just understand. You don’t have to explain a million things and give 50 pages of preface before you can start the book. So yeah, I feel like my roots are on Long Island because that’s where I grew up. And I like the food; I can relate to the eggplant parmigiana [laughs]. But on the other hand, the kind of person I am, you can just put me in a place and I’ll make it my home. I’ll try my best to put my roots in any place that I wind up.

Did you feel anxiety moving to San Diego? Because it felt like you had just created a moment for yourself in New York with Beyond. Things were happening. And then you just picked up and left.

VIC: I guess my priorities are not really on the same page with most people’s priorities—or maybe it’s kind of difficult to understand my motivations. Because at the time, my motivation was that I wanted to get into Krishna consciousness. I wanted to learn more about Krishna. I wasn’t so interested in the fact that I was in a good band or anything like that. So the problem with getting into Krishna [in New York] was that these people that I knew since junior high school, these friends I had, they don’t know “Bhakta Vic.” They know Vic, the skateboarder, or the BMX guy, or the guy who plays Metallica and Anthrax songs on his guitar. So to switch over, it was really difficult. Our relationships define our identity, and when I’m in this situation with these people who are defining my relationship as “the old Vic,” I can’t really transform into “the new Vic.” So I really wanted to go. I wanted to restart my identity. I welcomed moving to San Diego.

That’s interesting to me because, on some level, that’s how I felt when I moved to Chicago in 1998. Texas is the Reason had just broken up, and everyone was expecting me to start a new band, and my only concern at that point was coming out. I needed to worry about this part of my identity that was being underserved, and I believed going into a new physical space would hopefully transform whatever I needed for my interior space. Did it work out that way for you?

VIC: It entirely did.

At the same time, it feels like there must have still been a conflict. Because if you moved to San Diego to become more of a devotee, you still started Inside Out, which wasn’t exactly a Hare Krishna band.

VIC: I think my “Krishna hardcore” thing went through three phases. The initial phase was the end of Beyond and the Inside Out era. And then the second phase was the Shelter era. And then the third phase was the 108 era. And I think they’re really different actually.

The characteristic of the first phase was that I was oblivious to [the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, the largest institutional organization of Hare Krishnas also known as] ISKCON. I was oblivious to the idea of a preaching movement. That wasn’t a part of it all. I just thought, these are really cool ideas. They put all of these other ideas that I really liked—like vegetarianism or sobriety or equality—in one context, and they gave it some kind of common foundation. That worked for me. And that’s why it worked in Inside Out with people who weren’t Hare Krishna devotees. Because I wasn’t either, really. I was still just me, and Krishna was a part of what I was, and they were into that.

But then, as a result of exposure to Ray [Cappo], and then with Shelter coming, Ray was really influenced by ISKCON. So his version of Krishna consciousness was, “Let’s preach and let’s refill the temples and bring people back to ISKCON and make ISKCON great again.” That became my second phase. It was about preaching: Let’s make people devotees. But that was sort of short-lived because I didn’t really get along with it so well. And then there was the 108 era, which I think I would characterize by saying, “This is my bhajan [devotional song].” This 108 thing is my bhajan. It’s not my preaching; it’s an expression. I think that’s what it was in my head, but functionally, I think it was still like a Shelter preaching kind of thing. Practically speaking, what I was doing was arguing with people.

You’ve always had an arguing spirit. Even in [your old Krishnacore fanzine] Enquirer, you had that “I Wish I Was There Interview” thing, where you focused on using a debate model. I went through a phase of that, but it became very tiring very quickly. I was just like, “I don’t want to debate anybody anymore, this is dumb.” Did you ever have that moment?

VIC: I’m 52 years old and I am still having that moment. That’s my nature. I’m a debating person. It’s hard on my wife. You know, it’s like, we don’t even have that many normal conversations. It’s usually me reacting to her idea or telling her how—what’s his name?—Tucker Carlson is not to be relied upon [laughs]. I just immediately analyze, super-analyze, and debate things. I can’t get away from that. It's hard-coded into my mind. It kind of sucks, but it’s probably less exhausting for me than it is for you because, for me, it’s sort of natural. It’s the way I think and move and breathe.

Did you feel that way as a young person?

VIC: Certainly. From the beginning. If you look at my father, I’m a carbon copy of him. That’s the way my dad acts too.

I remember watching you over those first bunch of years—definitely when you were in Shelter, and then later, in the early 108 era—when it felt like you were philosophical to a fault. Like, everything had to fall into some sort of philosophical shape or you just didn’t engage.

VIC: It’s obsessive. I think maybe I’m obsessive with this.

Which is funny because it felt at odds with the creative person that made all this music. That’s where I felt the “emotional Vic” lived, although every now and then I’d get to see him in real life.

VIC: Yeah. I don’t know how to respond, but that’s me in a nutshell. Sometimes people think that I oscillate. But I don’t oscillate. I just have two very different extremes in one person. I’m a very lovey, gushy, gentle kind of person, but I’m also a fucking pain in the ass that likes to rip things to shreds and criticizes everything. They coexist in the same person.

I want you to take me into your brain in the ‘90s for a second. You had this reputation for being a Krishna fanatic back then—this didactic, very by the book, almost hardline kind of devotee. Did you feel like that’s what you were?

VIC: That thing was me wanting to be good. You know that “good boy” thing you told me about? That book?

“The Best Little Boy in the World.”

VIC: Yeah. I think it was that dynamic. I wanted to be Krishna conscious, and I had ISKCON telling me that if I wanted to be Krishna conscious, you have to do X, Y, Z and A, B, C. So I would do X, Y, Z and A, B, C, and I wouldn’t add E or F or G. I think it’s that simple.

That’s where you and I really differed. My experience with Krishna consciousness was more like, if you told me to do X, Y, Z, I’d say, “OK. I’ll do X, Z, G, and D” [laughs]. And I think I infuriated some people. I think there were times I infuriated you.

VIC: You mean the potato chips?

For one thing, yes! Like, I was sitting in my room [in the temple], eating some potato chips because I really hadn’t acclimated to eating temple food at all and I was starving. And instead of just asking me, “Hey, is everything OK? Why are you eating potato chips?” You freaked out on me and threw them out the window [laughs]. I remember walking out of the room and being like, “Where the fuck am I? What the fuck did I join? This dude is seriously going to get that mad at me for eating potato chips?” But also, at the same time, I was empathetic. You were doing something you believed in, and I don’t know what the potato chips triggered in you.

VIC: I mean, my personality is like a mudslide. It might not move for a while, but when it decides to move, it moves and you can’t stop it. It just goes all the way in a certain direction. I never really do things mildly; I do everything intensely. So with Krishna, it was like, “Yo, let’s fucking go back to Godhead!” I didn’t want a church with a nice social addition to my life with a spiritual community, I wanted fucking liberation. It was like, you want me to fast for six days? Let’s fast. Get these fucking potato chips out of here. What are you going to ask for next, a pillow? [laughs]. I think that’s where my head was at, Norm.

I think that I’ve always been skeptical of rules for rules’ sake—even when I lived in the temple. I’m OK with guidelines. I’m OK with rules even, but it needs to make sense to me. I’m not just going to say yes, yes, yes.

VIC: I think, in a sense, maybe you’re smarter than me with that. And also maybe you had less of a need to please these people. I have a people-pleasing problem, too. Believe it or not, I don’t like to get into conflicts with people. I like to get into conflicts with people on ideological things, but I don’t like to on other issues. I don’t want to make people upset with me. I want people to like me. So I think I was trying to please these leaders in ISKCON.

Knowing what’s an implementation of a rule versus what’s the essence of a rule, that takes intelligence. And it took me a while of trial and error to realize what the essence of this thing was. So I didn’t stay like that guy for the whole time. The guy that was in Philadelphia ISKCON, getting mad about your potato chips—in my defense, that was me in my first year in a temple.

And also, to put this into more context, I think one thing people neglect to talk about when they talk about Krishnacore and this whole thing we did in the early ‘90s is that we were all kids back then. I was literally a teenager. You weren’t much older. Ray wasn’t much older than that. So in some sense, we were still growing up.

VIC: Yes, definitely.

When you think about that growing up now, is there an example of anything where maybe you look back and think, “This wasn’t the best thing”—like, is there somewhere you think that you should have turned left instead of right?

VIC: I mean, everything. Just joining ISKCON. I shouldn’t have turned in that direction. ISKCON is fucked up in every possible way. That’s the thing. The stuff that I’ve done, the music I did and the creativity I had, I’m proud of it. And I’m also embarrassed by it. Like, it’s embarrassing to say that I fell prey to a cult. I joined a cult. What the fuck did I do? And I convinced myself that it wasn’t a cult. It’s like when a person is in an abusive relationship and they convince themselves that their partner is not abusive. They’re like, “It’s OK, they’re a nice person!” I didn’t want to admit that I had gotten myself into this cult because that would have proved that I have no judgment, or that my judgment is bad. I think it’s the same thing in abusive relationships where it’s embarrassing to the person to admit their partner is a shithead because you picked this partner and you attracted this partner. I feel the same way about ISKCON.

Although I think it’s important to say here that in both of those cases, I would not necessarily cast some sort of blame on the person who is embarrassed. That person did nothing wrong. It’s more like the analogy of the frog in boiling water. That’s more how I felt. You may have been attracted to the people-pleasing aspect of it, but I was interested in the surrogate family aspect of it. Like, I needed a family and I didn’t have one. That was my reason. And that’s a legitimate reason that I think people join cults. Were you looking for something when you found Krishna consciousness or did you stumble into it?

VIC: Very much looking. I wasn’t necessarily looking for a religious thing. But I think the same thing that got me interested in Dungeons & Dragons is the same thing that got me interested in ISKCON. And that’s not to cast dispersions on either one, but it’s just to say that I felt like, “This world that I can see in front of my eyes, and what I have access to with my senses is boring me. Isn’t there something else?” Yeah, there’s something else. Let’s play D&D. Or it could have been drugs. But it turned out to be Dungeons & Dragons and then punk rock and then came Hare Krishna.

You mentioned earlier that you may have some complicated feelings towards 108 and the music you made at that time. What can you tell me about that?

VIC: One thing I regret is that getting into Krishna isolates, right? It isolates an individual from others. In later 108, I wasn’t isolated from the rest of the band, so the creative process was so much more interesting because it’s not just a mirror of my own self. It’s bouncing off other people’s crystals and they’re adding their own colors into it, and it’s coming to be this unique thing that I wouldn’t have come up with myself. But post-Shelter, especially in the first two 108 records, it was like, I was doing every fricking thing—even the drum fills. I did everything, and I don’t like that in retrospect. It’s boring. It’s always too much of something or too little of something else. I regret that.

The other thing I sort of regret is that people would hear or connect with 108 stuff—with our message or whatever it was, our spirit through 108—and then that would impel them to go to a temple or something. I regret that because even though we were trying to be people-pleasers and everything, still, if you look at it objectively, 108 was really rebellious to what ISKCON is. The Krishna consciousness that a hardcore listener would get by listening to our band would be completely different from what you would get from going to a temple. So I feel like we kind of pushed some people over the cliff who wanted to go into a temple and who became a part of it, and then a couple of months later were like you, thinking, “Where the fuck am I? What is this? This isn’t what they were singing about.”

There’s a point where 108 becomes inactive and you are in your last real role in ISKCON, as a temple president in New Jersey. And then you get married and you leave and you’re just living in the “real world,” quote-unquote, for the first time in many years.

VIC: I don’t think I’ve ever been in the real world [laughs].

OK, then, you are outside the cult! What is that acclimation process like for you? How much did you struggle with the fact that you dedicated so many years to that mission?

VIC: It was a lot. I think also that [former Inside Out singer] Zack [de la Rocha]’s success with Rage Against the Machine also exacerbated things. It was difficult for me to deal with the fact that this guy that I was making music with before I started this whole thing is, all of the sudden, A. doing this really good music, and B. very financially successful—which is now an issue for me because I could use some money. So it was sort of difficult to process that. The acclimation process, I think it took a long time. It was very slow. And then I had to deal with trying to figure out who I was besides a Hare Krishna. Besides being a Krishna devotee, who am I? I’m also this weirdo, an intense weirdo, and it took me a while to explore that kind of stuff too.

We talked earlier about moving to San Diego as an “identity reset” of some sort. Did you look at moving to Japan in a similar way?

VIC: Moving to Japan was sort of an emergency reaction to a nuclear bomb. There were a lot of practical things that were going wrong at that time. 108 had started going again in 2005, and that was good and bad because it’s like when you give a kid access to the candy store: It might not be good for their health. I was very needy for people’s attention and love and everything, so if you give me access to a stage or a position of respect, you might want to keep a close watch on me. My behavior was not ideal, romantically speaking. And that put a pretty bad injury into my marriage around 2007. On top of that, we owned a house, and if you remember 2007, there was that subprime mortgage crisis. We were literally two days behind the back of the down wave, and we had to declare bankruptcy. When you declare bankruptcy, there is this seven-year penalty [on your credit] or something—and in America, it’s pretty difficult to live with a seven-year credit penalty. So we wanted to go somewhere we could restart ourselves.

We had been visiting Japan a lot over that past couple of years and we loved it. [My wife’s] family is here. We really liked her grandfather, who died at 98 a couple of years ago. He was this Buddhist priest and he was just a really nice guy. So we thought, let’s give it a try for a couple of years. Which is insane—I mean, you can see, I have no roots. Like, I had two kids in elementary school at the time and I just picked them up and moved them to Japan. It’s not even another English-speaking country.

It’s arguably the least English-speaking country.

VIC: Yes! But I don’t know. There’s good and bad to everything. So anyway, we all came here and everybody liked it, actually. And then three years turned into five and five years turned into ten. And then all of the sudden we inherited land from the family and now we have this land.

What did that move wind up doing for your sense of self?

VIC: I think it was pretty healthy because it let me be me. I mean, I’m so isolated now. I can’t even make new friends here because my [Japanese] is so bad. Like, I can barely talk to a first-grader [laughs]. So I can’t really make new friends and my old friends are in a completely different time zone. But I think that worked out in my favor because now I can sort of say: This is me without any outside influences. This is me when it’s just me. This is the Vic straight out of the box without the additives and not plugged into any other Legos.

Do you think you could have been the devotee you were without 108?

VIC: I thought I could. That was my thing. But then as soon as I left Shelter and I tried to do 108, it wasn’t really so easy. You’d remember that because you were a part of 108, actually. And then I went to Vrindavan [for Krishna devotees, a holy place in India] for the first time and I was like, “This place is great. This is where I want to live. I want to live here and die here. I love this place.” But the gurus [in ISKCON] were like, “No. You’re not allowed to do that. You have to keep preaching.” So that was the 108 dynamic back then; it wasn’t something I actually really wanted to do, but I had to do it. I always kept thinking I would actually be better off if I could stop doing this hardcore stuff and go live in India as a real monk. I was like, “Why aren’t they letting me do that?” I always thought it was because they’re running a cult and they want people. But I also think there was a part of it where after a while, I think it was in 1996, they finally said, “All right, you can stop now”—and I don’t know if it was a coincidence or not because a lot of other stuff also happened at that time, but it was a very short time between 1996 and 1997 when I was out of there [laughs]. I just said goodbye.

I think once I stopped doing 108 [in 1996], I realized right away that this isn’t right. I don’t fit here. And I had this huge moment in my life where I had to figure out which way I was going to turn: Was I going to turn left or turn right? Should I basically kill myself in India or should I take this totally different path and wind up having kids and a house and everything? I’m not really sure what convinced me. Maybe my hormones convinced me, like: You’re not going to make it over there in India. You’re going to be frustrated. It’s going to be bad for you. You just need some genuine loving.

It’s funny because I remember having these conversations with you in like ‘97 or ‘98 where it felt like you were at a place, maybe for the first time since I’d known you, where you like, “I feel like I need friends. Friends are good” [laughs].

VIC: Friends are so good! I wish I had more contact with you and Rob [Fish]. But even the people before you, like Kevin Egan and some of the people who came to our last New York show—those are people I remember playing Star Wars figures with. That’s like mother’s milk or something. It’s so comforting to have those people around. It’s difficult not to have that. But then again, that’s the person that I am and I wouldn’t be the other things that I am if I did have that.

OK, then. Speaking of friends, I have to ask: Were you aware of that Inside Out “official” Instagram post that went up earlier this year?

VIC: The whole “What’s the lineup for 2024?”

Yes.

VIC: Oh, Norm. This is a problem. This is another problem. I don’t want to be rejected again! [laughs] No, actually, I’m so out of it that I think I became aware of that post for the first time yesterday or a couple of days ago. I don’t know. But to be honest, it’s kind of a good question because that is a big sore spot for me. That’s a huge sore spot. Like, why did I leave Inside Out? I was so fucking stupid, right? To become a Hare Krishna. So [doing something together again] would be great. That would be healing. That would be fun. But it would kind of suck if it makes me realize that I burned my bridges so badly that these people don’t actually want me to be a part of their thing. I would hate that. That would be a sad moment.

Did you perceive that to be a messy split?

VIC: I think it was. You know how oblivious I can be. I can just be really oblivious to people’s feelings. I think I was almost entirely oblivious to what Inside Out meant to Zack or what it meant to the other people in the band, and I didn’t give a shit about that because I knew what I needed for myself. It was selfish. Even in my entire obliviousness, I could tell that they were emotionally upset. It was at the Vic Theater in Chicago, where I said, “After this tour, I’m not going to be in Inside Out anymore.” And they were just sitting at the table and… you know what it’s like when faces go blank. Like, the person looks like they could kill you or something without feeling anything? Not hateful, but just entirely blank. They just shut off.

I think when I dig into it, I really need to forgive “Bhakta Vic.” I was 21 years old. I think I’m allowed and expected to do immature things at that point. I made a dumb move, from an artistic standpoint—leaving a creative partnership with Zack in favor of a creative partnership with Ray—and also very likely from a career standpoint. But 21-year-olds make dumb moves. It’s how we learn to be less dumb later.

As it stands, 108 seems to exist in this sort of ambient way. Never fully gone, never fully present. I wanted to get your take on that. Is there some sort of comfort in having an “ambient 108?”

VIC: I think that “ambient 108” is an influence of [bassist] Trivikrama. People like Rob and me, we’re very clear cut. That whole thing of, like, are we a band or are we not a band—whenever we try to call it quits, Triv is always like, “No, no, no. It’s OK.” So it’s OK [laughs].

But the thing is, I had an interesting conversation with Rob a couple of days ago, and it’s like, I don’t feel like playing in 108. I don’t feel like doing it. And I think part of the reason is that I’m not upset anymore. I’m not angry at much and I’m not upset with much and I don’t have money problems. And therefore it doesn’t feel like there’s a need for me to go play these songs, which are confrontational, and that music, which is confrontational. Maybe this is a bad thing to say to a hardcore crowd, but it’s not like I feel inspired to wake up and put on Agnostic Front like I used to. I mean, if I put it on, I feel great. If I put on a Crumbsuckers record or something, I get a surge of energy and I feel great. But I just think 108 isn’t necessarily the band that I’m motivated for anymore. Honestly, I kind of think being happy is not good for 108.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is CRUCIAL to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

Norm <3 u so much for doing this, and doing it so well.

This was awesome! I particularly connected to the analogy of involvement with ISCKON and embarrassment over attracting or choosing an abusive partner. I have definitely experienced both and have never really thought about that correlation.

There was one copy of Monkey on a Stick in my high school library that 4 of us shared. In 1991 it was not easy in suburban Long Island to access a book like that. We agreed no one would check it out so we could read it during breaks at school. By reading and knowing all of the details, I could always defend that I was going in eyes wide open.

Personally, 108 may have validated or made my attraction and interest in Krishna feel cooler, but it was never the impetus. As with most things I have been interested in and engaged with in life, I was always kind of on the fringe. One foot in, one foot out-definite personality flaw, but I don’t have any regrets about it in this case. Thanks for having and sharing this thoughtful and engaged conversation ❤️.