In Conversation: Jason Black of Hot Water Music

As Hot Water Music turns 30 this year, Jason Black is choosing to revisit the trials and triumphs with the benefit of hindsight, none of the nostalgia, and his focus on the future.

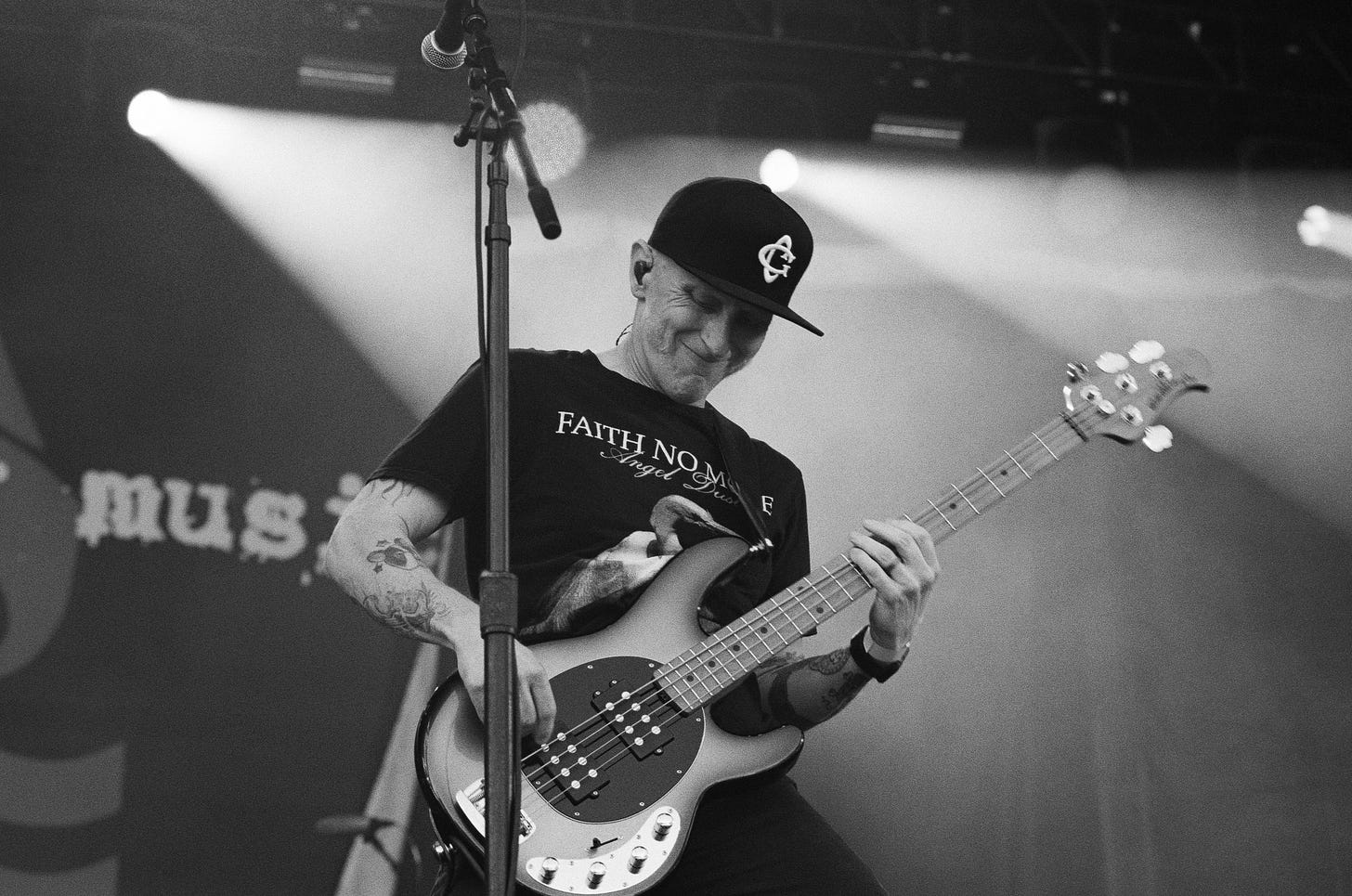

After three decades of history as a band, you would be hard pressed to land on a single narrative that could best encapsulate the story of Hot Water Music other than the fact that its four original members have all but promised that they would always do it together—or as bassist Jason Black tells me in this conversation, “It’s the four of us. We can add. We can’t subtract.”

This sense of both commitment and addition are more present than ever in 2024: They have a new album coming out in May, appropriately titled Vows. They’ve fully integrated a fifth member in Flatliners frontman Chris Cresswell—who plays a significant (and excellent) role on the new record. They’ve also invited a number of friends to feature on it: Among them Popeye Vogelsang of Calling Hours, members of Thrice, and Daniel Fang and Brendan Yates of Turnstile, who literally named their band after a Hot Water Music song. Vows is somewhere between ceremony and celebration.

But before we could get to all that, Jason and I had to address the elephant in the room: This interview marks the first time that he and I have spoken since 1996, when Hot Water Music and my band, Texas is the Reason, found ourselves in a feud that never quite resolved itself. So we begin by mending fences.

This is kind of wild, but I looked it up yesterday and our story begins exactly 28 years ago—on March 15, 1996.

JASON: I had to look it up too because I thought it was 1999-ish, but when I saw it was 1996, I just thought it was so crazy that it was actually that long ago.

What really hit me is that we are randomly doing this on the literal anniversary.

JASON: Total full circle [laughs].

Obviously you know what I’m talking about, and I know what I’m talking about, but I think most people have no fucking idea at this point.

JASON: There are definitely people who are like, “Oh, I guess that was a thing, wasn’t it?” And it was a thing for sure.

So I guess the first thing that I’m curious about is this: To the best of your memory, why are we in a feud?

JASON: OK. I don’t really know! As I say that, I should almost preface it with the fact that where this happened, at the Hardback [Café], we played there so often. Local bands would play there all the time. There were months where we would play there three or four times. So I could definitely be conflating shows. I also have a terrible memory—and I drank back then. No excuses, just facts [laughs].

But what I remember is that we played a show with you, Gameface, and Frodus. And these are the flashes that I have of it. At some point, Chuck [Ragan] was definitely drunk and he fell backwards into Gameface’s kick drum… I remember that. And I remember that when we were playing, it was like, “OK, we have to stop”—after three songs. I’m not going to single anyone out because it was probably everyone at that point, but we were just awful because everyone was so wasted. And it was probably like 12:30 in the morning because shows started late there. So that’s what I remember. But I’ve been thinking about it since we set this interview up and I’ve been thinking about us as individuals back then and wondering about other contexts. Like, George [Rebelo] has always been pretty mellow and definitely not a loudmouth. Chuck was… I don’t know if he even knew where he was, at least based on my memory. But Chris [Wollard] and I were loudmouths, so it was very possible that one of us said something totally offensive. But for real, I don’t actually know [laughs].

I completely forgot about Chuck falling into the drums. That was a fact. And it was a problem because Steve [Sanderson from Gameface] was setting up out in the parking lot because the club was too small to do it inside, so his drums all basically just hit the concrete—hard.

JASON: That was burned and seared into my memory. I remember thinking I would be so mad if I were them, totally.

I also remember Garrett [Klahn] told us that you guys were talking shit about us on stage. This is tough, because that’s not a direct memory; that’s what he told us. So as far as I was concerned, I was like, “Fuck that band” [laughs]. But then, a couple of weeks later, someone told me that I had to read a thread that had been posted to alt.music.hardcore. I don’t know if you have any memory of that.

JASON: Not that I remember, no. I’m not even sure if I had a computer at this point. Maybe I did, but I don’t know.

It appeared to be someone from the band giving their version of events from that night. And I remember some wild accusations—like someone from our band shoved one of your girlfriends, which was total bullshit. So it just got more heated. I was like, “OK, fuck you, let’s do this” [laughs]. But I think the alt.music.hardcore part is what makes it most interesting to me because it reminds me of a time when the internet was so fresh and brand new, and we could have been using it for good, but almost immediately, instead of trying to clear things up we were like, “Nope. We’re just going to fucking dunk on each other.”

JASON: God, I feel like I was just discovering Instant Messenger and Juno in like 1998. It was like finding the Matrix. But that period of time was wild for us. 1996 was maybe around the time of the second record. I was still in college, so all of our shows were either during the summertime or on winter break. In hindsight, it was a really weird time for us. Like, you guys were at a show that was a really good example of it. I don’t want to say it was a tumultuous time for the band, because I feel like bands are always tumultuous, but we were 20 and 21 years old. We didn’t know shit. And I think a lot of it was really just fighting through the questions of, “How do we do this? How do we do this band thing? Do we want to do this band thing?” I feel like most bands start with aspirations. It’s like, “Let’s make a demo tape. Let’s play this show. Let’s do these other things.” But we were in this awkward period where even putting out a record was like, “We can’t even believe this is happening.”

That’s a really interesting distinction between Hot Water and Texas because, obviously, coming from New York, most of our friends were on major labels in 1996. Or they somehow made a living playing hardcore. And that was kind of something that had to happen because living in New York is expensive, so if you can’t sort of make money from being in a band, you’re not going to have a band for that long. But you seem to be saying that there was not so much a lack of opportunity, but maybe a lack of imagination for where you could go.

JASON: For sure. In hindsight, that’s definitely something that none of us ever thought about—like, how could it be so expensive to live somewhere like that? When we first started playing in Gainesville, we got the cold shoulder, big time. There was more of an East Bay, Gilman Street vibe here. It was the kind of thing where George had a nicer drum kit than everyone because he had been playing death metal before we started, and people would make fun of him for that. Or they made fun of me for having a bass that wasn’t a piece of shit. I was like, “But I put it on layaway!” We were treated like we were taking this too seriously—because we practiced [laughs]. Also, we were more in the Samiam, Seaweed, and 7 Seconds-derivative zone than we were in the Crimpshrine, Fifteen, kind of backpatchy zone. That’s what kind of town it was until we made friends with everyone. But some of that still stuck around for a while, where people would come to our shows and make fun of us, heckle us. Even people we were kind of friends with.

There wasn’t anyone out here that had signed to a major label until Less Than Jake signed to Capitol, and the backlash here was fucking crazy for them. People just stopped talking to them. It was like, “How could you sell out?” For a chunk of time, we were living in the become-what-you-hate zone—where we were shunned when we started, and then we forced our way in the door, and then when anyone succeeded beyond us, we became the people who shunned us when we started.

My understanding is that you have never been approached by a major label.

JASON: That’s true, still.

I’m sort of wondering if you had a band philosophy about that or if it’s just something you never think about because the opportunity never came up.

JASON: I’ve probably gone back and forth like crazy on this, but I don’t know that we would have said no if it came up because that’s just one of those things where you can always think “I’ll never do that”—until someone shows you something that’s possible and you’re like, “Oh, that’s a whole new world of things I could potentially do!” Like, pay rent, even [laughs]. So it was a little bit of both. There was definitely a thing of “we’ll never do that,” and then also, it’s just kind of hard to say you’ll never do something that you’ve never had the chance to say no to.

OK, so let’s go back to this period of time that you were describing, with this reckless version of Hot Water Music running around, and it very much feels like you’re careening towards your first breakup, which was in 1998. Obviously, we are now talking about the band in the context of your 30th anniversary this year, which is wild, so we can also maybe say that this first breakup was your first brush with mortality.

JASON: Oh, definitely.

How did those few months of being broken up clarify what it was that you were doing? Did you come back from it thinking differently about the band?

JASON: Yeah, we did. That breakup happened on our first European tour, which was basically five weeks in Germany—as a lot of tours in Europe were back then. At some point in the tour, I don’t know if George quit, but that was sort of the vibe. Either he quit or he wasn’t happy, and he was like, “This sucks. We’re playing to three people in Germany, I don’t have any money, everyone is broke. This isn’t what I wanted to do with my life.” That kind of thing. Like, “This has been fun, but whatever.” So we just wrapped that tour up—with no fight or anything—and we were like, OK. This isn’t really going to do it for us. But then we got home and we were convinced to do a final show and to record it for a live album. And we started rehearsing for that and then ended up writing three new songs. It was like, “Oh shit. Maybe we do like playing music with each other and being in this band!” We just needed to learn how to do it a little better. It’s taken us 30 years to learn how to do it a little better, but that was the first… “brush with mortality” is a really good way to put it. Because we were really broken at this point. This was not sustainable. There’s no way this works. So that was an important thing to have happened—because a forced break, for whatever it’s worth, gave us a lot more energy when we started back up again. It was like, now we’re ready to really go for it.

After that, we went from kind of careening around, like you described it, to being a little more organized and methodical. That’s when we did the record with Some [Records], and when we met Walter [Schreifels] and all those guys, and when we did our first tour with Sick of it All. The only other band we had really done a good amount of shows supporting was Avail at that point, so we didn’t have a leg up on doing anything like that. But now we were meeting our heroes, and we were on their label, and we were going on tour with our other heroes—all these people we grew up listening to. We were a part of this ecosphere that was way more exciting and seemed like it had a lot more opportunity. And that kept us going for a while.

Was there a point when you were forced to start thinking about Hot Water Music as a “job?”

JASON: It was right around then when we started making enough money to slide by on rent here for the most part, or at least keep real minimal jobs when we were home. We were doing well enough that it seemed like we could kind of make this happen—which, in hindsight, is crazy because we were probably getting like $250 a night on that Sick of it All tour, but we were like, “Awesome, that sounds great, let’s go!” [laughs]. So yeah, that was right around 1999, when No Division came out. We were technically a full-time band from there on out where we would just work to some extent when we were home and then we would tour as much as we could.

I think there’s another side to this question, which is that the economy of a band changes the longer you stay together. Like, back in the ‘90s, most of us had very few expenses beyond rent. We were young, so it’s not like we had families. But as you get older, your expenses change, the cost of living changes, the overall economy changes, and your band somehow has to keep up with that. Has that ever felt like a friction?

JASON: Oh, definitely. I mean, we just felt that friction recently. Right before the pandemic hit and then again right after, we had come back into this model of doing weekend shows. We were doing record-plays—flying out, doing two nights at this club and two nights at that club, and playing subsequent records each night. That was working really well for us. We would fly out, rent backline, maybe rent a van if we were there for a couple of days, get some hotels, and do the show. But then afterwards, when things started to open back up and we put out Feel The Void, our last record, we tried the same model and we fucking ate it. Comparatively, tickets were more expensive, planes were more expensive, hotels were more expensive, and it never came back down. It just blasted that model. I feel like, for us, it’s always like, “I think it’s really going to happen this time! Things are going to be smooth!” And then it’s just like, nope! Not quite [laughs]. And that’s probably the way it is for everyone right now, to some extent, unless you’re one of the very few bulletproof bands out there.

I remember when Thursday had six members, I was always asking them, “How the hell does that work economically?” [laughs]. You guys actually added a fifth member recently, so I wonder if economics was part of the conversation at all?

JASON: No. It’s not like we have a super convoluted structure, but as far as that all works out, I think it turns out to be about the same. Because when we’re touring, we’re still only four. And then Chris [Wollard] doesn’t tour, but he still gets income from certain aspects of the tour. We have it all worked out to where everyone feels cool about everything and it’s somehow a big happy family [laughs]. But there may come a day when Chris is like, “Hey, I’m going to go back on tour”—and then we’ll have to figure out how to be a five-piece on tour. It’s just going to be what it’s going to be. I hear you on six people, though. That’s a lot of people!

Even from a decision-making standpoint! I’ve always been blown away by anyone’s wisdom of being like, “Let’s add another member!”

JASON: We were very lucky that it worked out so well. We knew Chris [Cresswell] for a while beforehand and it just feels normal now.

I think that one of my early impressions of you—and maybe this is partly related to our ill-fated first meeting—is that you guys, the original four, seemed like a very insular unit. You were kind of in a bubble. Is that something you’d agree with?

JASON: In 2012, when we kind of came back for the 500th time, we recorded Exister with Bill Stevenson at The Blasting Room. He told us, “You guys don’t sound like a gang. You need to sound like a gang of people with baseball bats that are coming after everybody.” Like, “gang” is a little bit of an aggressive description at this point, but when he said that, it kind of hit me in a weird way. I was like, “Dude, you can actually hear that, can’t you.” And it was true. That was kind of a sticky time for us because we came back to make that record and we actually weren’t in a great place as far as communication with each other. We didn’t really feel like a gang anymore. Back when we first met, we weren’t a monolith 24 hours a day, but I think once we got into the band mindset—we were, definitely. It was that way and then it sort of fell off.

You once said that the band made a “pact”—and I don’t how literal that was—but you said that you made a pact that you wouldn’t do Hot Water Music again if it wasn’t the four of you. So I’m curious how you started to process it when Chris [Wollard] shared his mental health struggles with you, and you maybe started to realize that you might be one man down?

JASON: It was definitely weird. It was right when Light It Up came out, which out of all of our records is the one that I’m like, “Ah, we fucking phoned that in.” Even though we didn’t think we were phoning it in at the time, in hindsight it was like, ugh. We decided not to do so many shows on it as well. Riot Fest was one of the shows we did. So we went [to Chicago], and the day that we were supposed to play, Wollard just seemed off. I should probably say here that George and I had already both been through panic attacks and anxiety; we were well-versed in fighting them off constantly. But we just never had any indication that Wollard had ever been fighting with this. And I don’t think he knew either. So we did those shows and we went home and that was kind of it. I didn’t think anything of it other than seeing him a little off that day.

I don’t know how long after we got back from Riot Fest, I was talking to Wollard and he was like, “Hey, I had to go to the doctor. My heart feels really weird.” He had all of the symptoms of anxiety and panic attacks, but he just didn’t know yet, so he went through a battery of exams—which I had to do, too, when I was going through it. But he still hadn’t really settled on what was going on with him. We did a couple of rehearsals for Fest [in Gainesville], with just me, him, and George, and it seemed OK. Rehearsal seemed fine. But he was still getting this kind of vibrating, dizzy, spiraling feeling if the music was too loud or if he was singing too much, and the day before we were supposed to play, Wollard called and was like, “I can’t do it.”

At first, I thought we could try to do it as a three-piece because, well, it was already happening. Chuck had flown in the day before, and in theory, Wollard’s just sick, so maybe we could just knock these shows out because we’re already here and we can collect ourselves later. We had actually already hit up Cresswell about singing one of our songs with us because we had just done a tour with the Flatliners and we were thinking that, since Wollard wasn’t feeling so great, we could take a little bit of the load off of him with that. So we wound up asking Cresswell how many songs he could learn in one day, and then an hour later he was like, “I’ve got six” [laughs]. We did half the show as a three-piece and half the show with him. We did two shows like that. And then we had some other shows already booked, so we asked Cresswell if he could fill in for those. Wollard was cool with it. He was like, “The shows are booked. People bought tickets. Let’s just do it this way and we’ll figure it out afterwards.”

Was there a sense of panic in your brain yet or did you just really believe this was a temporary thing? Like, at what point did you realize, “Wollard is not going to tour anymore.”

JASON: I don’t know when that actually hit. I mean, I could look back and think about when I would talk to Wollard and be like, “Do you want to do these shows?” And he’d be like, “No, I don’t think I can do these”—and then eventually it was like, oh, OK. This is the thing. Eventually, our booking agent or someone asked if we wanted to do something for the 25th anniversary of the band, and the conversation had to turn into, “Are you cool with Cresswell doing this?” And Wollard said, “Yeah. This is what Bad Religion does. Brett [Gurewitz] plays on the records and he doesn’t go on tour.” So we just went from there.

The only time it got sticky is when we started writing Feel The Void—because we’d never written as a five-piece before. This is just from my perspective, but it seemed like you could kind of see that Wollard was like, “What am I doing? What’s my role?” And then Cresswell did it in a way that was… I don’t want to say “respectfully” because that’s almost condescending.

I don’t think so. As someone who has stepped into a long-running band myself, I’d say that’s probably fair.

JASON: Yeah. I mean, it ended up working out. Everyone left their ego at the door.

Do you think that the members of the band were sophisticated enough to be able to approach Wollard’s situation with total empathy or were there moments of selfishness?

JASON: Oh, there were total moments of selfishness—especially because George and I had already dealt with it, you know what I mean? At one point, we were like, “You should do this or you should do that, and also, you’re fucking hanging us up here.” I’m an only child, so all of my moments are selfish on some level [laughs]. But yeah, there were definitely those kinds of moments from everyone, at varying degrees for varying reasons at varying points of time. Because things were going well! And we wanted to keep things going well. Things finally felt sustainable in a reasonable way; it just felt good. It was like, “We’ve hit a stride, and we want you to keep being a part of the stride with us, but we can’t do the band without you.” And I’m so glad we didn’t decide to try to do that. I don't know what magic happened to where it ended up with us being a five-piece and working, but it did.

The four of us did have one phone call where we just fucking let it all out, and that hadn’t happened in a while. And that, I think, is sort of what set the tone for everything being awesome moving forward. It’s just that we are so fucking bad at communicating with each other because everyone has all their built-in PTSD from being in a band with each other for so long. That phone conversation was finally the point where I feel like we finally got past that.

Was there ever a point where you thought, “Oh, so… about that pact…”

JASON: [Laughs] No, I don’t think so. I think there was always the majority bringing it back to: No, it’s the four of us. We can add. We can’t subtract.

You’re about to go out and do a 30-year anniversary tour—and we can do the math here [laughs]. So I wanted to talk a little bit about your experience with aging and especially in the context of adding a member to the band who is fifteen years younger than the rest of you. Does that secretly amplify any self-consciousness you may have about getting older?

JASON: I think that for as much as it’s amplified how old we are sometimes, it’s been mostly helpful. Even after the first two shows we played with Cresswell, Chuck was like, “Fuck, I gotta get in shape” [laughs]. But I mean, [Cresswell] was like six when we started the band! Like, I’m probably the guy out of the four original members that tries to… Well, let’s just say I’m not leaning into my age. I’m not a fan of getting older. I don’t hate it because I’m definitely a better human being, and I’m really happy about that. But I haven’t just given up and been like, “Welp, I’m an old guy, so that’s how it is now!” So for me, personally, it’s been nice to have someone around who is still so excited about a lot of things and has a voracious musical appetite.

Naming the new album Vows feels very provocative to me in light of what we’ve been talking about. Like, our bands started at roughly the same time, but I could not fucking imagine being in my band for 30 years [laughs]. Was this part of the thinking in naming the record?

JASON: Well, we’ve been working on a documentary about the band with the crew that have made all our videos for the last couple of records, and Jesse [Korman], the director, he actually came up with the title for the record. He was like, “There’s this recurring theme where it feels like you guys keep talking about renewing your vows.” Through making the documentary and talking about the history of the band, and then writing all the songs, the overall topic for the record really seemed to be about how doing what we do is like planting a seed and taking care of it as it grows—and how that’s a commitment. This is our 30th anniversary, but we’re putting out a record and we’re going on tour and we’re still going for it. So it’s kind of like renewing your vows. It felt right when Jesse brought it up, and I also liked that it was coming from someone who wasn’t in the band. I put some stock in that because sometimes it’s hard to get any perspective when you’re so deep in it.

OK, there’s a thing that Chuck said once that I kind of wanted to get your take on here, but I feel like a lot of people would give a diplomatic answer and I really want you to dig a little deeper.

JASON: [Laughs] You got the right guy then!

Chuck said, “When we came back together, we said that if one of us doesn’t want to do it, or if someone bows out and we have the blessing to continue, then there’s no reason to break up anymore.” That last line just really stood out to me, because I do think that’s a very modern idea that a lot of bands have taken to heart. Never having to break up is a real thing for a lot of bands right now. So I guess I wanted to ask you—from where you personally sit in terms of your own goals or objectives with music or your own experience with this band—at what point do you think you actually “need” to break up?

JASON: That’s a very good question because I think about it a lot. It’s an interesting time because for the past ten years I’ve had a full-time job. I started it when I lived in Brooklyn and then I took it with me when I moved down here, but I was just “downsized” or “let go” or whatever the nice version is of “you can’t work here anymore.” I’ve been working for a long time. So my answer to this is definitely different today than it would have been six weeks ago, before I knew that was the case—or at least, I think it would be.

I don’t know if I heard this from somewhere else or not, but it’s how I think about it now: Every time we make a record, we should feel like this is going to be the one. Whatever that means for each and every member of the band. It can be this is going to be the one that makes sure that we can just be this big forever. Or this is going to the one that makes us huge. Or this is going to be the one that everyone talks about in 20 years. Or you shouldn’t make it. Because there’s definitely guys in the band that are like, “It’ll be the same thing it always is. It’ll come out and everyone will seem excited and then our shows will go back to what they were before”—and that might totally be the case! But for whatever reason, I don’t ever want to buy into that when we’re doing something new. That kind of self-sabotage, self-defeatist thing, while it may be more realistic, it takes the fun out of it for me. I think that’s the thing I really like about making records: You don’t really know what’s going to happen. Because what you think about it as the person who had a hand in creating it is so different from how everyone else receives it.

That said, I kind of don’t want it to be enough. I really like playing music and I like collaborating with people. I like doing things like this [interview]. I like talking to people about music and bands and what they’ve done. This is enjoyable to me! Especially having just had a job for ten years that just felt fucking soulless—where I was like, this is great because I don’t have to worry about where my money is coming from every week, but also, why would anyone choose to do this?

But I also think something that fucks up people in bands a little bit is that sometimes we feel like we are entitled to only having a job that we somehow enjoy [laughs]. Most people have maybe never had that once.

JASON: Yeah, it definitely fucks us up for sure. That is very true. But at the same time, while it does make us have this inability to do things we don’t like, I’m kind of OK with that. Because at this point in my life I probably have less time now to be alive than I did ten years ago. So I kind of want to do something that I feel as good about as possible. As long as everyone’s down to keep pushing the envelope and doing fresh new things, I’m ready to go for more.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is CRUCIAL to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

Great interview with my all time favorite band. The Wollard insight hit me so hard. To one day not be able to do what you do and love... I’m glad he is still a part of the hot water family, even if he can’t be out on the road with his brothers.

Great interview!