In Conversation: Brian Cook of Botch

When Botch reemerged with a new single two years ago, they signaled the start of a reunion tour that was two decades in the waiting. Now that it's all over—again—Brian Cook is ready to reflect.

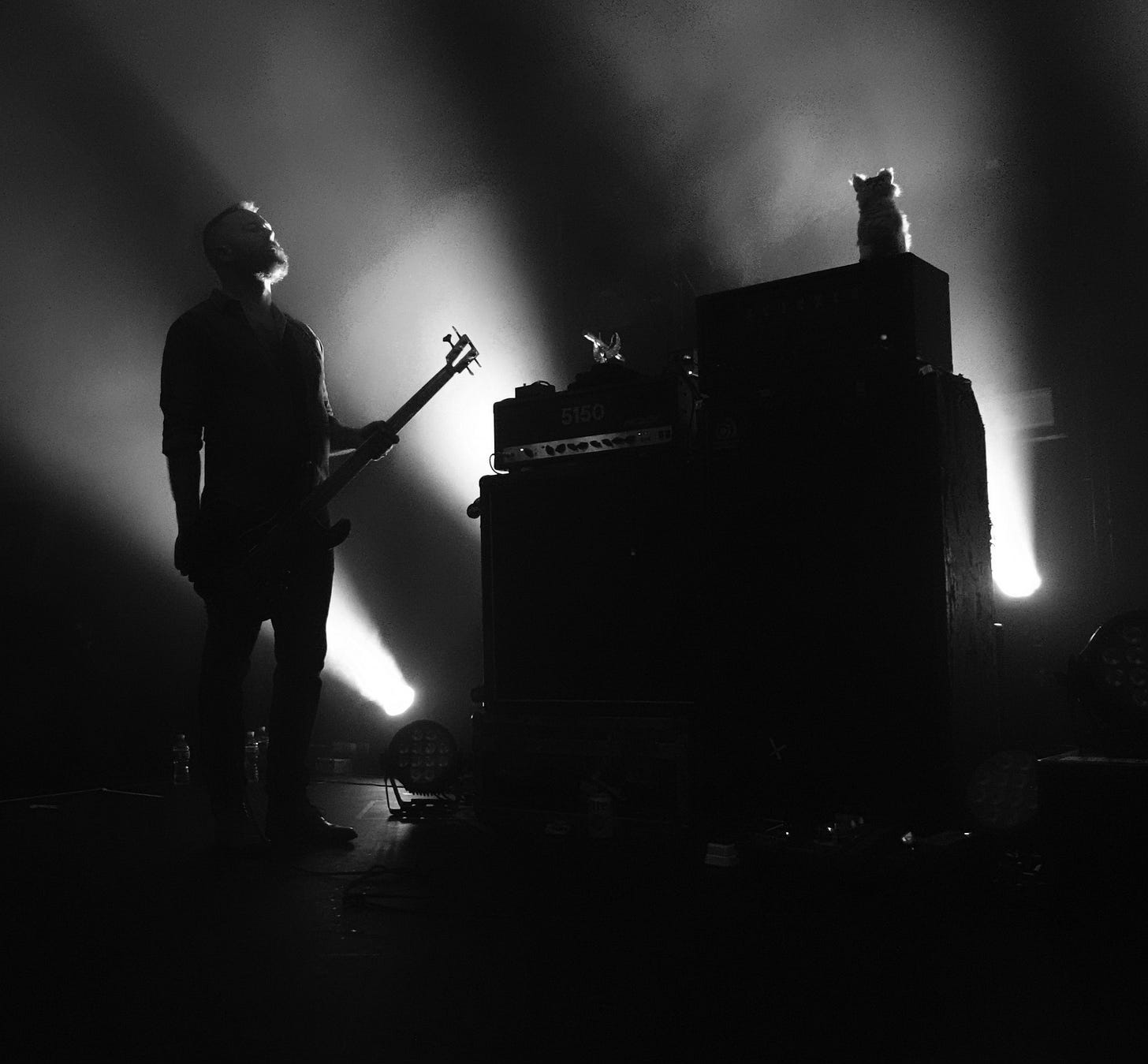

By the time you read this, Botch will have played their final reunion show at the Showbox in Seattle—almost 22 years to the day that Botch played the final shows of their original run as a band, also at the Showbox. It was a thoughtful ending for a band that truly put thought into everything they did, even if it was impossible to predict the scope of their enduring influence on hardcore and metal in the decades between. It’s easy to get cynical over reunions, but after seeing Botch play last year at the New York City stop of their tour, I remember telling a friend that they seemed to be honoring the songs as much as they were playing them. The love was palpable.

As the band prepares to wind down again, this time for good, I asked bassist Brian Cook to sit down for a retrospective—not only about his life with Botch, but with respect to his own personal journey before and after the group. The love, again, was palpable. “I think a lot of my music career, I really owe to Botch,” he tells me. “I owe it to those guys.”

I know you were a military kid, and that before you landed in Washington, you actually grew up in Hawaii—which, if you are coming from the mainland, can definitely feel a little isolated from the rest of the country. I wanted to start by asking you to tell me something about who you were when you got there, and how you acclimated to that change.

BRIAN: Well, I was born in Kansas, and I spent like six months in Kansas City, but I have no real memory of that. After that, my family moved to Washington state, where my dad was stationed at Fort Lewis. And then we were stationed outside of D.C. But that was all before I was five. We moved to Hawaii when I was just ahead of starting kindergarten, so I didn’t really have that much of a frame of reference about the mainland.

My formative years, from 1982 to 1992, were all on Oahu, which is unusual because people in the Army usually get moved around every two to three years. But my dad is a doctor in the Army, and at right around the time that we were two or three years into living in Hawaii, he went high enough in rank that we were able to stay put for a longer period of time. In the end, we were there a total of ten years. Hawaii is where I first heard punk music, and it’s where I first started playing in bands, and it’s where I went to see shows. It was all on Oahu.

How much of your socialization there was rooted in your family’s religious background?

BRIAN: My family is very religious. My grandfather on my mom’s side was a Baptist minister in Colorado. But they are also pretty progressive in a lot of ways, particularly for rural churchgoers. Maybe not compared to the mores of today, but like, my mom helped her college roommate pay for an abortion and things like that. So we were a lot more laid back than most conservative Christian military families, but I still had to navigate that.

I think being in Hawaii was really good for me, though, because it’s such a mix of cultures and perspectives. You very quickly learn that there are a lot of different ways of living when you’re out there; you learn about a lot of different cultural values. Most of my friends growing up were Japanese. We lived in Kailua, which at the time was just a tiny little beach town with predominantly Japanese kids in my classes. It led to a headspace of being open-minded, for one, but also—and I know this is weird to say—it made me used to being a minority in some weird way, because I didn’t have any white friends. That stigma of being a haole, especially as a kid, was real. Like, I got called “ape boy” in grade school because I had hairy arms and no one had hairy arms in school [laughs]. But I do think being exposed to a lot of different things made me a more open-minded person than I could have turned out to be.

The first time I went to Hawaii was in 1998, which was still before the ubiquity of the internet. You left Hawaii before the internet was even a thing, so I would imagine that the version of punk that you discovered had to have some kind of unique regional flavor, in the way that a lot of small towns before the internet had their own unique versions of punk.

BRIAN: I mean, it really was a very culturally removed place. I didn’t even know about the culture of zines until I moved to Washington. So for me, the only way I really got to know about music was through Thrasher or through skate videos. After that it was word of mouth and maybe some cool record store clerks. And also the catalogs that would come with records back then—like, how if you bought something on SST, it would come with a whole SST foldout catalog inside of it. One of the big early exposures for me was Firehose and Minutemen, who I thought must have been these enormous punk bands… Until I moved to Washington and realized no one cared about those bands up there [laughs]. But the SST stuff was really big in Hawaii, whether it was, obviously, Black Flag or Descendents, but even Hüsker Dü and Dinosaur Jr. They were all considered huge, huge bands. Hardcore wasn’t really on my radar in Hawaii, outside of, you know, Minor Threat or Gorilla Biscuits or Bad Brains.

Were you excited about the move to Washington?

BRIAN: I was, just because by the time I was fourteen, I was already sort of aware that Oahu was a really tiny place that was separated from a lot of the things I was interested in. But there’s a real dramatic change in the way people socialize between Hawaii and Seattle. Like, Hawaii is very friendly. It’s island life, so everyone knows each other and everyone is friendly and invites you to do stuff. And then you move to Seattle where there’s “the Seattle freeze”—where it’s just very Scandinavian, and everyone is polite, but everyone keeps you at arm’s length. It’s really hard to crack into social circles in the Puget Sound area. Being on a military base, you’re at least surrounded by other people who are transplants and maybe not as closed off in that regard, but it was still a tough adjustment. And I think just the scope of how big America is can be daunting when you go from living on an island that you can cross in 40 minutes to seeing the I-90 ramp and being like, “Damn, that goes all the way to the other side of the country.” That’s fucking insane [laughs].

At the same time, I think I was also aware that I’d be closer to all this music stuff that I was excited about. You know, I went to the same school as Aaron Stauffer from Seaweed. His dad was my swim coach. But for as big of a cultural epicenter as [Washington] was for underground music at the time, there was also the Teen Dance Ordinance, which meant that it was almost impossible to host all-ages shows in Seattle. I knew cool shit was happening, but most of it was either 21-and-over or I just had no way of getting there because I didn’t have any friends and I didn’t have a driver’s license. So I just had a solid year of isolation where my exposure to punk music was just going to the mall and buying Circus Lupus tapes or whatever I could find.

You could also say that Botch is your high school band. You all went to the same high school.

BRIAN: Yes.

But you weren’t all even necessarily hardcore kids to start with, right? Like, it just seems like you wanted to play loud music.

BRIAN: Right. It happened really quickly because I met [guitarist] Dave Knudson in math class, in junior year. I’d overheard him talking to another classmate about trying to find a bass player to start a band, so I chimed in. Dave’s reference points were more towards the heavy end of alternative music—like Faith No More or Soundgarden, and then, you know, some straight up metal like Metallica and whatnot. But he also knew Dead Kennedys and things that were in my zone of interest, and I was just excited to find anyone that wanted to play music, period. Because I’d spent a year trying to find people that wanted to play punk music and I couldn’t find anyone. So that was exciting.

He’d already been playing with Tim [Latona], our drummer, and Tim liked a lot of heavier stuff, but he was also still more of a classically trained jazz guy. He is the actual musician in the band who knows theory and can talk about all that stuff. And I have no idea what Dave Verellen was into, but he was excited to be a part of it. So that all came together in October of 1993. I want to say that Dave K. would have just turned sixteen, so he had just gotten his license. He was the first person that could drive us to shows. One of the first shows we went to was Undertow at a local community college, and I think that was kind of the moment where we were all like, “That’s what we need to fucking do. That’s fucking cool.” We all kind of immediately started listening to Undertow and Strain and Unbroken and anything that seemed adjacent to that. We were all really excited about that new world, but there were a couple of hardcore kids who were a little older than us at school who were like, “Oh, a month ago they were playing fucking Helmet covers and now they’re covering ‘Firestorm.’ Like, this is pretty suspect.”

I was reading an interview with Dave [Schneider] and James [Bertram] from Lync the other day. They were talking about being young and going to shows in the general Washington area, and how—they didn’t say this exactly, but—it basically felt like one big scene. Meaning that one night they’d go out and see Beat Happening, and Calvin Johnson would be dancing around in an “Art Fag” shirt, and then the next night they’d see Undertow, and then, as they suggested, everyone loved Brotherhood. The idea was that there weren’t enough shows and bands to really musically segregate Washington too much at the time. Is that how you experienced it?

BRIAN: I mean, if you were only into hardcore and you only wanted to listen to hardcore, then you had one option, and it was Undertow [laughs]. You had to be a little more open-minded. Some of it also goes back to the Teen Dance Ordinance thing, where it was like, you couldn’t play an all-ages show in Seattle, so you had to play teen centers on the East Side, or you had to play the Capitol Theater Backstage in Olympia, or you’re doing house shows. It wasn’t unusual for us to have to drive an hour to go see a show in a basement, but it was worth it because that’s all there was. Seeing a band like Lync? That was exciting. If it was seeing Ten-O-Seven? That was exciting. It definitely felt like it was all under the larger banner of punk, and that’s what mattered.

There’s a famous story that [Undertow vocalist] John Pettibone once told about how a couple of unnamed members of Botch came up to him as kids and basically asked him if they could be straight-edge [laughs]. Fact or folklore?

BRIAN: I have no memory of that, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen [laughs]. I feel like there might be a little stretching of the truth there because I don’t think we were quite that naive, but who knows. We were certainly young and certainly very green and definitely very much in awe of Undertow. I know there was definitely some awkward fan-boying going on. But they were always nice to us. They were approachable people who hung out in the crowd until it was their turn to play.

How did starting the band and trying to get Botch off the ground intersect with your own coming of age, especially in terms of your sexuality and being in the closet? You must have known by that point.

BRIAN: You know, I was a late bloomer. At that point I was already aware that the feelings that my friends had towards the opposite sex just weren’t happening for me. At the same time, it was the early nineties, and I hate saying this because it sounds narrow-minded, but my perception of “what it meant to be a gay person” at that age, and in that time period, it felt like, “I can’t possibly be gay because I don’t like dance music. I don’t like show tunes. I don’t want to dress that way. I like skateboarding and hardcore.” Even in terms of what I realized I was attracted to… It was like, I’m not attracted to Calvin Klein underwear models. Anyone who was an attractive pop star or a famous actor that was supposed to be attractive, that wasn’t doing anything for me. But like, the pro-wrestler I just saw? The pro-wrestler does something for me, but that must be entirely something else [laughs]. It was a lot of just not understanding, and a lot of fear of coming out, because it was just so taboo and different in the early nineties—especially coming from my upbringing. I guess part of me still thought I could grow up into being a straight person. I just didn't know what to think of it.

That said, I think punk was really important because records like Minor Threat or Dead Kennedys or Operation Ivy—any of that stuff that you first hear when you’re getting into punk music that has a very strong message throughout it—the recurring message is: No. The world around you is wrong. You being yourself is the good thing. Having to change who you are to please other people is the bad thing. Having that notion ingrained in me over and over again was probably the reason punk meant so much to me. And I think, subconsciously, that’s why I’ve kept at it. Because I feel like it provides a space for people to be themselves. And even when hardcore and punk so often turns into being a straight, white guy club, it’s still way more progressive and inclusive than any other sort of civic group that I could have been a part of in 1992 in Fort Lewis. It was like, no, this is the progressive shit. This is the radical shit.

Did you have any specific fear about coming out as a member of Botch?

BRIAN: A little bit. But Botch was the first place where I came out. The guys in the band were the first people I came out to. And they didn’t care. Tim was even like, “Oh I’ve been telling people that for the last six months. Anytime a girl would start asking about you, I was like, ‘Don’t even bother, he’s gay’” [laughs]. I do think there was a little bit of fear that people would treat me differently, but I didn’t worry about losing friends or anything like that. I worried that coming out would change the way people behaved around me or that it would create this awkward tension where they felt like they had to atone for any gay joke they had told in years past. I didn’t want to have to navigate all that. But in terms of the broader punk and hardcore scene, I think I was really proud to be out—just because there were still a lot of knuckleheads and a lot of macho posturing and whatnot. I mean, I remember playing shows and making speeches about being gay, and that just felt like the right thing to do. I had no issues, really.

Well, this wasn’t Botch, but there were those issues with Underoath when you were touring with These Arms Are Snakes.

BRIAN: Which was weird. I was really “anti” any of that Christian hardcore stuff in the nineties because, for me, punk and hardcore was a place where I felt like you could be queer and not feel threatened. And to all of a sudden have a bunch of church kids come in… It was like, come on. You have your youth groups, just stay the fuck out of this. It was only by meeting people like David Bazan [of Pedro the Lion] and this guy Jeff Suffering, who was part of the Tooth and Nail [Records] family, that I could see that these guys who were Christian and they were progressive. They were progressive radical people who just happened to have faith. And it seems like their faith is a very genuine thing, where they can still be critical of the church and analyze their own feelings. I’m cool with that because it seems like an examination; it’s reflective and not bigoted.

The only reason we did that Underoath tour is because all these people vouched for them. We had done a random one-off with them on tour once, and they seemed like nice people, so we signed up to do a U.S. tour and it was like, night one, you hear these guys who were skirting around using any sort of swear word—like they wouldn’t say damn or hell or shit or fuck—but then they’ll just say faggot, no problem. I had a shirt that said QUEER on it and I would wear it every night and they still didn’t get it. They would just say “faggot” around me. And I wasn’t mad because I would take the Lord’s name in vain around them [laughs]. The context of how they used the word wasn’t actually aimed at gay people, it would be like, “Oh, I want to talk with the fans after the show. I don’t want to sit on the bus and have them think I’m some sort of faggot that’s too cool to talk to anyone.” But it was like, Why does it have to be that word? Our booking agent got word about it, though, and she got mad. She called their tour manager, and then their tour manager pulled me aside and gave me this really long apology. I appreciated the gesture, but it’s not like he was the one using the language.

I thought everything was cool for the rest of the tour, but then on the last three or four days they had to hire a new merch person. And their new merch person had been talking to our merch person, and he was like, “Oh yeah, [Underoath] mentioned that I had to be really cautious about how I talked around you guys because you guys are really sensitive about gay stuff. Those guys were like, ‘Brian is cool, but it’s people like him that are the reason we vote for Bush. So people like him can’t get married.’” No one told me that until the last day of tour, when we were in the van driving away, and I was like, “Motherfuck, they fucking said that?” I thought we almost got through this whole tour without me hating these guys. But it was like, wow. Fuck you.

It’s interesting to me, because as we talk about this, I’m thinking about how Botch were peaking at the end of the nineties, which definitely felt like the decade of “the big message”—and I guess Christian hardcore was part of that. But the big message was also something Botch seemed to reject, and even mock, on “C. Thomas Howell [As the ‘Soul Man’].” Was that a deliberate kind of thinking at the time or was that just how it rolled out?

BRIAN: For me, I liked songs that were about things. Even before punk music, I remember hearing Michael Stipe from R.E.M. saying how he hated writing love songs because every pop song is a love song, so it felt like the most played-out, insincere thing. To hear punk bands sing about issues, that was really meaningful. It felt genuine. They’re angry and this is what they’re fucking angry about. That had a huge appeal. I would have loved for Botch to have been more of a message band, but it all goes back to: Where are your actual strengths? I would have loved to have been Los Crudos, and to be able to have these speeches between songs that were super powerful and meaningful, but, like, none of us are public speakers. None of us can do an off-the-cuff inspiring message-to-the-people between songs, you know? [laughs] Every once in a while, I’d help write some lyrics, and I actually wrote the lyrics to “C. Thomas Howell.” There’s a few songs in the catalog where I felt like I’ve got something to say. But I don’t think that was Dave Verellen’s real interest. I think he liked stuff being a bit more abstract and open to interpretation.

We were also coming into the scene at the same time that there was stuff like Unwound and Karp and all the Gravity Records stuff that was really exciting to us. And there was almost an absurdist quality to a lot of that. Antioch Arrow just seemed like they were trying to piss off the punks by deliberately not saying anything and throwing around words that had no loaded content to them. There was something about that that felt very subversive, even towards an already subversive subculture. But what I think it came down to [for us] was that no one wanted to be preachy and bad at it. So we just kind of skirted around it.

I almost feel bad about “C. Thomas Howell” because I think that song came across as a mockery of bands caring about things—which wasn’t the intent at all. Me and Dave Verellen wrote it, and for me, the whole point was that I remembered a few friends going down to Goleta Fest in ‘98. First of all, I love that whole Ebullition and Goleta scene. I love Struggle, I love Econochrist, I love Iconoclast. I love how all those bands wrote songs that had strong political stances. But I was talking to my friend after he played it and he was like, “God, every band was like five minutes of talking about animal rights, then a two-minute song where you can’t understand a single word, then five minutes talking about how the cops are bad, and then a song that was just indiscernible noise. It was just so uninspiring.” Hearing that, and seeing how that scene was already leaning, it just didn’t feel like anyone was really doing anything new. And it’s really disappointing because this music can get real tired, real fast if you don’t pepper it with other things. And if it’s really bound up in all this ideology, then you can get cynical towards the ideology as well as the music, and that’s even worse. I don’t want to be a cynical person. But it seems like there’s a risk of that happening if all my worldviews and beliefs are tied to this weird style of music that you can very easily get burned out on. That was what “C. Thomas Howell” is about, and I don’t think I translated that very well into the song.

I was actually going to say that the two bands that get associated with that song most in the press have been Racetraitor and Earth Crisis. But then I found something you wrote in The Stranger about Earth Crisis in 2008 where you basically said, “‘Firestorm’ is one of the best straight-edge songs in the world ever.’” I was like, wait. Was there a change of heart? Or were you just being contrarian?

BRIAN: At no point in time have I ever not liked the Firestorm EP! At the time that it came out, I thought it was the heaviest thing I’d ever heard. It was so intense. There’s plenty of things about Earth Crisis that could be easily criticized, of course, and maybe even poked fun at. But to me “Firestorm” has always been just fucking sick. Even if, in reflection, there’s something dodgy about singing a song about rounding up a “chemically tainted welfare generation”—I don’t know how I feel about that, but great song [laughs].

Are there times where you maybe wish Botch weren’t as contrarian as you were?

BRIAN: I think being contrarian in some aspects made us a stronger band, because if you wanted to piss off the hardcore kids and you wanted to make a song like “Dali’s Praying Mantis” where the beat keeps getting displaced and you can’t actually even nod your head to it, all that kind of shit was its own brand of contrarianism against doing easy, flashy chug music. But I do think there’s a certain amount of contrarianism, musically speaking, that was also our undoing. There’s something really unifying about having something that you’re pushing back against; bands tend to flourish when they’re united and pushing against something. At a certain point, though, if your artistic vision is based on just negating something, then you’re not really being a creative person. You’re sort of just taking an idea and dismantling it and trying to recontextualize it, but nothing is coming from the well of your creative spirit. It’s like you’re just deciding what you don’t like in modern music and then slowly eliminating options.

Honestly, I feel like what you’re saying in some ways reminds me of my experience with Texas is the Reason, because we actually created a lot of self-imposed restrictions on what we were doing. And I think the more rules and restrictions that we created for ourselves, the harder it actually was to function creatively and personally. It was almost like, yeah, of course we weren’t built to last.

BRIAN: I think there’s a very similar parallel with Botch. I mean, one of the big things with us was that melody, in general, was pretty verboten. Every once in a while, there’d be something that felt like a conventional melody in the music, but in general, we wanted to avoid that as much as possible. But once you take melody out of the equation, you’re already eliminating so many possibilities for things that you could do. We just handicapped ourselves in a lot of ways, and we ultimately broke up because we weren’t feeling creatively inspired. We put too many rules on ourselves.

This is a good segue, because I wanted to talk about the reunion and also these rules that we put on ourselves. You’ve said a lot about reunions over the years, and one thing in particular that you said was: “‘Reunions equals bad”’ was ingrained in my head from very early on.” This is not an uncommon position. Historically, even in the eighties when bands reunited, punk kids would talk shit. That’s what we do. There had to be a level of deep deprogramming that you had to get through to change that ingrained position.

BRIAN: Sure, well, I think to start with, it’s important to know that Botch broke up because we weren’t getting along and we were struggling to be a functioning creative band. But we were still popular. We arguably broke up at the peak of our popularity. And from the second we broke up, there was just a constant stream of reunion invitations. It was constantly being introduced as an option.

Dave [Knudson] was doing Minus the Bear, and I was doing Snakes. I had no issue with Snakes being presented as an “ex-members of Botch” thing because I was proud of Botch and I felt like Snakes, on some level, was a continuation of what Botch was doing—without being afraid of throwing some more conventional rock tropes in with it. But I know Dave K. was really hesitant to ever attach Botch to Minus the Bear because he wanted them to sort of flourish on their own merits. I think for the two of us there was a thing where we had current projects going. There was a degree of appreciation for what we had done in the past, but we didn’t really need to continue on with it. Botch had its own kind of closure; the last show was great. As far as ending a band goes, it felt very tidy and complete to me. But over time it became apparent that even though I felt a lot of closure and felt good about it, Tim and Dave [Verellen] didn’t necessarily feel the same way. There was a feeling that we could have done one last tour or done a few more shows or at least have gone to Europe. They felt like there was some unfinished business.

Even though we broke up with some hard feelings, those guys are still my friends. They’re still important people in my life. A lot of it for me was just that I always had current bands and I was always busy. I was proud of what we’d done, but I didn’t want to rest on my laurels and continuously do victory laps for something that was no longer active. I just thought people should go to shows to see bands that are still creating something. So that really weighed heavily on my personal decision.

But you know, Snakes broke up. And Snakes basically broke up because I quit. It got to the point where I had way too much band debt on my personal credit card, and it was just a self-sabotaging band where I knew going forward it was just going to be more messy and more financially ruinous. I still wanted to do some final shows, or maybe a final tour—I wanted that same kind of closure—but the other guys were just so upset by me leaving that they were like, “No. We’re not doing anything.” And so, for me, it always felt like that chapter wasn’t finished. Now fast-forward twelve years later and there’s an opportunity for Snakes to do these reunion shows [in 2022]. We did them, and I got that sense of closure. I was like, “Oh. We’re finally not just a bunch of like drunk dudes that are stumbling around on stage, barely getting through these songs! We can actually be somewhat of a functional band and actually have people at the shows that are excited to be there!” That was a very rewarding experience. And I think that kind of made me realize that I was kind of withholding that experience from two people who have wanted that for twenty years. It was kind of a tough realization. I really had to rethink things from that angle.

There’s also one last thing, and this might not translate very well, but I think a lot of my music career, I really owe to Botch. I owe it to those guys. And I have no qualms in saying that Tim and Dave Knudson were much better musicians than I was, and I’ve learned so much from those guys, and I took things that I learned in Botch with me into Snakes and into Russian Circles and into Sumac. I wouldn’t have had those opportunities without Botch. But at the same time, I feel like at least a little bit of the reason there is a continuing dialogue about Botch is because people in the band continued doing music. So there’s this weird thing to grapple with in terms of how much of this do I owe to the guys and then how much of this is a thing that I’m having to grapple with just because I’ve continued to play music?

You’re about to head into your final shows for this reunion, and I know you must be thinking about everything that’s happened in the last year, so I kind of wanted to end with this. Can you think of an experience or moment in this final year of Botch shows where you really felt like getting the band back together was the absolute correct decision?

BRIAN: Yes, but I think that moment probably wouldn’t even be a show. It would be the four of us hanging out in a room, talking shit with each other, and working on something together. I think the most valuable aspect of it, for me, has really been reconnecting with old friends. And I realize that might sound sentimental, or maybe even disingenuous given the scale of how big the tour has become, but you know, I’ve had that real rush and joy of playing music constantly for 22 years since Botch broke up. Playing a good show hasn’t been something that’s been absent in my life. Doing it with Botch is fun and validating in a lot of ways, but the most valuable part of it really has been hanging out with the guys and enjoying each other’s company and seeing this friendship rekindle. All the tension that existed and all the bad feelings have drained away. So even though I’m looking forward to the last Botch shows so that I have a little more free time in my life, and I can devote more time to other projects or maybe be home a little bit more, there’s definitely been this revelation that I’m not going have this hangout time with those guys every few days—and that’s something I’ll really miss.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Your support is CRUCIAL to Anti-Matter’s continuation and growth. Thank you, friends. ✨

Really enjoyed this interview. This bit really resonated with me:

"...it just didn’t feel like anyone was really doing anything new. And it’s really disappointing because this music can get real tired, real fast if you don’t pepper it with other things."

Botch was never my thing, but I certainly appreciated that they were pushing the envelope and doing something pretty unique. That quote also represents how interesting so much of current hardcore and punk is, and how open kids are to various sounds these days. Seeing Ceremony seamlessly go from fast hardcore blasts to dancey synth-punk and the crowd being just excited for all of it is really inspiring. Seeing shows with bands as diverse and genre-pushing/bending/mixing as Angel Dust, Candy, MSPAINT, Gumm, and Miltarie Gun, and kids going off for all of them equally is so exciting.

It makes me think of all the bands that felt new and exciting, either musically or lyrically, when I was coming of age that now really feel like milestones in this music (Earth Crisis, TITR, Refused, Botch, Deadguy, Lifetime, 108... the list goes on).

Thanks for the interview, great to get to know a little bit more about the band and Brian after all these years. In like 94 or so I remember driving down from Vancouver Island to go see them play in a basement in Seattle with Integrity also playing. Such great memories of PNW hardcore at the time. I loved the Botch / Undertow / Excursion sound and style, particularly after what he's saying about the Goleta Ebullution sound, which I loved but kind of grew tired of. Anyway, thanks for sharing.