Constantly In-Between

I became a skinhead in 1987 because, unlike the rest of me, it felt like a simple identity to manage. It would have been more hardcore to embrace the chaos.

I.

Hardcore became a major concern of mine between 1987 and 1988. I had gone to a couple of shows before then—my first was an all-ages Crumbsuckers show on Long Island at the end of 1986—but it took some time before I began to see hardcore as my identity, and not simply as a weekend activity. The clues were in the language: We never asked someone if they “listened to hardcore,” we asked them if they “were a hardcore kid.” That’s not the same thing.

I was only in junior high school in 1987, which is to say that whatever identity I was wearing at that age was an identity of circumstance. I was a New York City native, a second-generation immigrant, a childhood Pentecostal. None of these were chosen; none of them inborn. What should have been my most obvious source of identity and belonging—a connection to family culture and ancestry—was somewhat mysteriously taken away from me by my father, who refused to speak about it. None of this made sense to me. My mother was happy to discuss how she grew up in Barranquilla, Colombia, and how her family were the descendants of Spanish and Portuguese immigrants. But my father, when asked, only ever said one thing: “I was born in Santiago, Chile.” If you pressed him, he would only repeat it. Like a captured soldier—trained to give his captor only his name, rank, and serial number—my father held onto that answer and never let go up until his death. I heard him say it so many times I can still hear it.

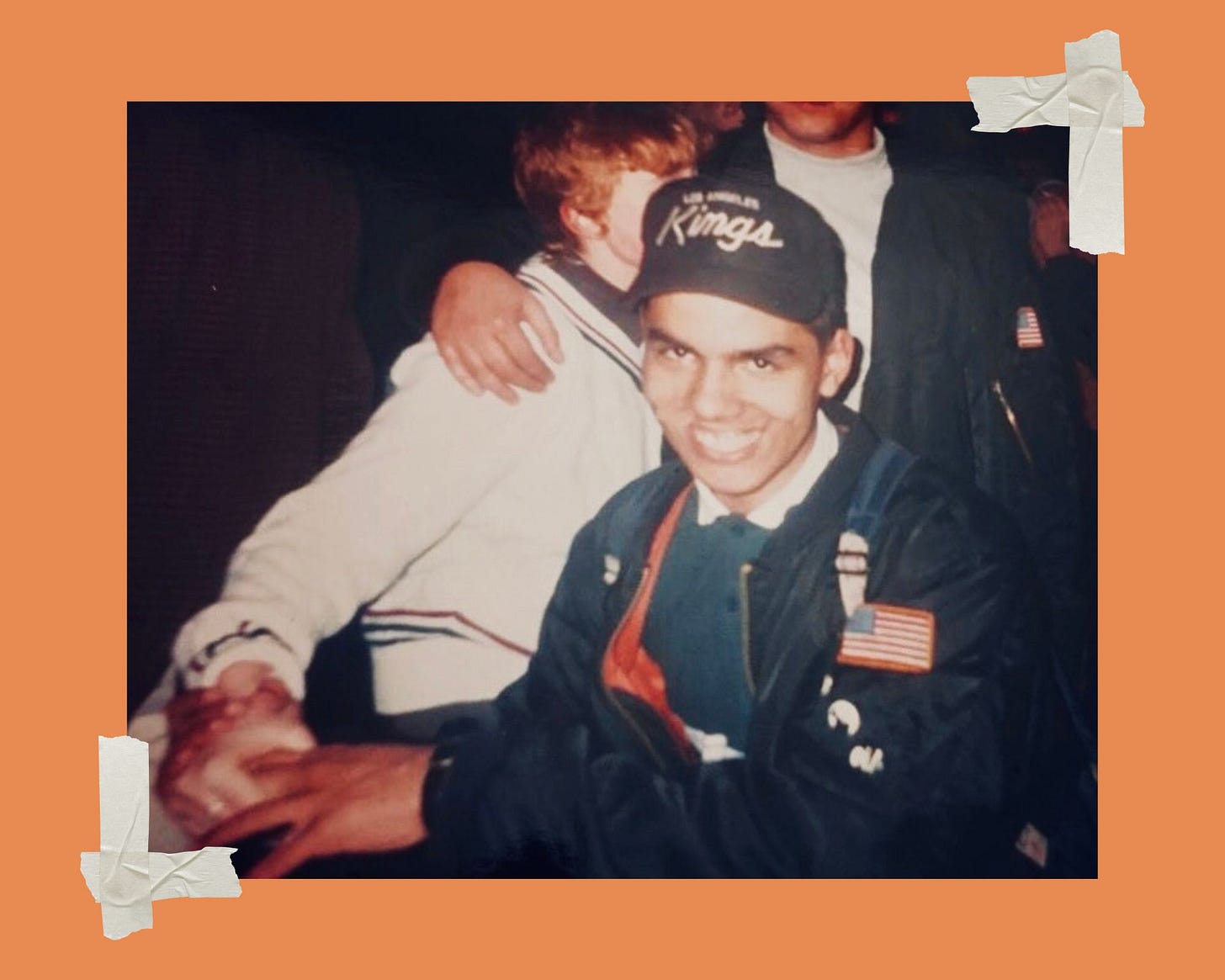

I came into the hardcore scene, then, with an even cleaner slate than most. I was ready to try on a new identity, and I was ready to commit myself to all of it. The majority of kids going to shows at that time were skinheads—or at least they dressed like skinheads—and that seemed like the best place for me to start. Skinheads had a clear visual identity, a haircut and a uniform. Skinheads had a national identity, which is why patriotism in the hardcore scene was a thing back then. Skinheads had a social identity, although I would have probably described my family as more “working poor” than “working class.” And of course, skinheads had an artistic and cultural identity—the music we loved, whether it be hardcore, Oi!, or ska. These were all fairly easy prescriptions to fill.

During my skinhead years, I didn’t have to think so much about the unresolved question of my ethnicity. I had always viewed skinhead culture as a hybrid British-Jamaican phenomenon; I saw racial diversity as something that was baked into its DNA. There were certainly racist skinheads who had begun making media waves in late 1988, but most of the kids in New York thought they were posers—“TV skinheads,” we called them. What I probably didn’t want to admit to myself at the time, though, was that there were lots of local skinheads who both didn’t identify as racist and yet still held what I’d call semi-racist tendencies. They bought Brutal Attack records “for the music.” They defended Youth Defense League when they thanked Skrewdriver in the liner notes for the legendary New York City Hardcore: The Way It Is compilation because “you can’t choose your friends.” In their more candid moments, they’d say things like, “I’m not white-power, but I am white-pride”—the distinction of which was never really interrogated. I grew up with some of these people, so for a long time I just let it go, thinking, “Some of this stuff feels shady, but I’m not white and they don’t treat me differently.”

But then one day I went to a party in Manhattan with one of my older skinhead friends. It was 1989 and he wanted me to connect with some new skinheads from Philadelphia that he’d just met. There was nothing different about that day and I wasn’t given any reason to think there was anything different about this party. We just buzzed to get in, and then one by one, my friend introduced me to the group. They looked like nice enough people to me.

“This is Norm,” he said, quickly adding, “He’s Spanish-Portuguese, a European.”

I had never thought of myself as “European” before, and I had certainly never identified as one. Regardless of ancestry, my mother identified as Colombian, so I did as well. It was the first time I’d ever found myself in a social situation where it felt like my darker skin needed some sort of explanation, but I didn’t correct him because it was also the first time I’d ever legitimately felt scared in a room full of white hardcore kids.

II.

For years, I resented my father for not giving me a clear cultural identity. I knew I was Chilean, but I didn’t know what that meant. Were his ancestors, like those of my mother, also European? Was my father actually indigenous? And how did any of that even matter in America, where people still randomly call me “Puerto Rican” or “Mexican”—as if the twenty-something different territories that make up Latin America are interchangeable and unimportant. To make things worse, my parents forbade me from speaking Spanish at home as soon I started school, despite the fact that they spoke Spanish to me. I grew up feeling wholly untethered—not “Latino enough” to feel fully at home with the communities of my parents’ homelands, not holding enough generational proximity from my immigrant parents to be spared from occasionally being told that I should “go back to my own country.”

As the half-Chilean, half-Korean daughter of immigrants herself, Crystal Pak from Initiate understands this sense of “in-betweenness” more than most—and it appears as a familiar sense of discomfort that presides over their latest album, Cerebral Circus. It’s something she and I really bonded over during our recent conversation, which will be published on Thursday.

“My mom had a really good tough love conversation with me once [when she was teaching me Spanish] because I would always ask her stuff like, ‘How's my accent?’” Crystal recalls. “She said, ‘Hey. The reality is that there are going to be some people on this planet who are going to tell you that you are never gonna be Spanish enough, and especially because of the way that you look’—because I'm more Asian-presenting. But the thing is, I think I know maybe ten words total in Korean. I was never fully immersed in Korean culture. So then what? I’m not really there either.”

As we were sharing our stories, I realized that the dissonance we felt was based on an expectation that identity should be tidy and clearly determined. It was based on the premise that a complex identity is inherently flawed. These were the same ideas that made shaving my head as a 13-year-old kid such an appealing proposition to me: Because being a skinhead is an easily defined way of being. It was an identity that felt simple to assert and gave me little to no psychic friction. It felt like the most uncomplicated identity in the world until the day I went to a skinhead party where being European or not seemed to matter.

III.

In 2018, a few years after my father died, I spit in a plastic tube and sent it to one of those DNA-testing sites. I needed to know what my father had been hiding this whole time, despite accepting that I’d never really know why he hid it. I needed to know, once and for all, where I came from. Even my mother, who had also died by this point, claimed to have no idea. For so long, I’d felt like half a person.

When the results came in, they confirmed what I already knew about my mother’s side: I was a descendant of Spanish and Portuguese ancestry, just like she said. But just underneath that, in an equal percentage, was a new designation. I am Native American. My father was indigenous after all.

Much to my chagrin, knowing that you are derived from native ancestry is not the same thing as being indigenous. To be indigenous is to have been raised on the land, in the tradition, and with the people. It’s not determined by blood, but by sweat. It’s not a neat-and-discrete identity I can just whimsically assume. According to most estimates, over 80 percent of indigenous Chileans belong to the Mapuche people—which is to say that it’s more likely than not that these were my father’s people. The Mapuche story is a centuries-long story of resistance against Spanish colonizers and latter-day Chilean tyranny. Perhaps there is something in that history that will explain why my father ran away to America, became an American citizen, and kept his children from knowing where he actually came from. But I’ll never know for sure.

IV.

If I’m being honest, many of the identities I tried on as a young person—both inside and outside of hardcore—were discovered while in search of simplicity. Being a skinhead was one of them, but so was being a straightedge kid (there are literally just rules to follow) or becoming a Hare Krishna (again, I really wanted rules). Growing up and not being able to embody my Latin heritage in any sort of truly deep-seated way took away a fundamental sense of belonging, and existing in that constant state of in-betweenness left me feeling more alienated than “American”—which is probably one of the reasons why hardcore resonated with me in the first place.

The thing is, I think I had it all wrong. I resented my “in-betweenness” because I saw it as an obstruction to having a single, cohesive identity, but I failed to see it as a cohesive identity in itself. When we pour an equal amount of red dye and yellow dye into a bucket of water, we don’t say that the liquid is half-red and half-yellow. We recognize its hue as orange, and we accept that color as distinct and valuable in itself.

During our conversation, I told Crystal about something I heard once that has become something of a North Star for me in this regard: There is a meaningful relationship between the word “integration” and the word “integrity.” Integration is knowing that you are everything all at once, and learning how to be as complex as you are without running away from it. Integrity is standing in the truth of that complexity, even during moments of discomfort, and knowing that you cannot separate the parts anymore when you are finally living as a whole person.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Crystal Pak of Initiate.

Anti-Matter is reader-supported. If you’ve valued reading this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and backing independent, ad-free hardcore media. Thank you, friends.

Wow. Another fantastic essay Norman. You don't hear many people talking about being Latino in hardcore and the many ways people try to identify us, the ways we self-identify, etc.

Reading this also made me think about the correlation between Latinos growing up ultra Christian/ conservative households and eventually identifying as straight edge when we discover hardcore. It was true for me, and definitely a lot of the kids I came up with in the South Florida hardcore scene.

This reminds me of Stuart Hall's 'New Ethnicities' essay from the early-90s.