Anxiety Asking

In spite of hardcore's enduring quest to erase the line between audience and artist, parasocial interactions are inevitable—especially in the internet age. There's still a lot of room to improve them.

I.

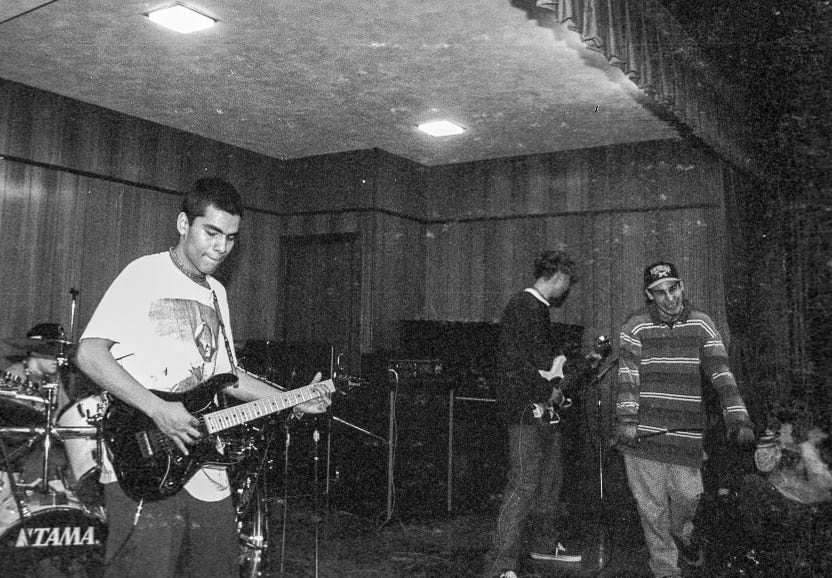

It was never my intention to put myself out in front of people. It was never a childhood dream; it was never a professional ambition. When hardcore told me that the kids on the floor were no different from the kids on the stage, I took that at face value—and in my mind, that’s what made participation viable. Whether on stage or on the floor, I only wanted to be a kid. In fact, I wanted to go through life avoiding detection. Because for a long time, that impulse was all I ever knew about myself. Some of that is a well-tread queer instinct—using invisibility as a strategy to deflect awareness from that secret—but the rest of it can be chalked up to a more universal reality: Being an object of attention makes me feel vulnerable in ways that, quite frankly, I still do not enjoy.

I grew up the youngest of three boys. By the time I was born, my mom and dad were already in their forties and fifties, respectively—which is to say that, as far as parenting went, they were over it. I wasn’t doted on, at all, but I also didn’t really act out for their attention. By and large, I kept to myself. I listened to music. I read books. I did well at school because I knew that meant everyone would leave me alone. I avoided social functions in general and found comfort in solitary pursuits. Writing was one of them. Playing guitar was another. I specifically gravitated to these activities because I didn’t need anyone else to do them. They were sources of personal expression, first and foremost. They were mine.

Therein lies the paradox of forging a creative path. You do this work, at least initially, for yourself—and by yourself—until you begin to feel the part that’s missing. Anyone who has ever made anything knows this. If every band who has ever said they “only make music for themselves” and “don’t care what anyone else thinks” were actually telling you the truth, they would be tucked away in their basements and writing songs in seclusion—their names intentionally (and perhaps, righteously) languishing in obscurity. If they were telling you the truth, they would admit that there comes a time when the work we do naturally evolves into more of a conversation and less of a monologue. At some point, we need other people.

Opening that door does, of course, entail giving up some level of obscurity. I discovered that as soon as I started putting myself out there. But as the work I did became more popular—and in spite of the rhetoric I believed about kids on stage and kids on the floor—I began to feel that I was, in fact, being treated differently. Not simply in a manner of admiration, which is natural and sweet and appreciated, but more so in terms of expectations. There was an assumption being made, over and over again, that I was a kind of person that I am not. That I was an extrovert who thrived under intense social conditions. That I was somehow predisposed for the public scrutiny, punishing criticism, and personal intrusions that sometimes go with growing up in front of people—and if not, that I was at least strong enough to handle it. These are the kinds of things that will continue to push many kids to give up participation and even more of them to refuse to try altogether. Meanwhile, the rest of us will be told, “You asked for it,” when those deeds come to pass—even if we didn’t. Even if we landed in this position because the things that we made literally resonated with people by articulating how alienated we felt and how crushed by expectations we already were.

II.

The story of this week’s interview with GEL goes back exactly one year, to September of 2023, after a run of shows that we played together. At the time, I was curious how they might go over with a typical Thursday audience, but night after night, they forcefully animated the crowd without pandering. GEL just did exactly what GEL does: They played their songs, one after the other, without any bells and whistles and with hardly any banter, and they connected with people purely on the strength of such a raw presentation. Honestly, it was inspiring.

At the end of that tour, somewhere in Virginia, I pulled vocalist Sami Kaiser aside and told them we should set up an interview for Anti-Matter. Without hesitation, they agreed to it, and I went on my way without sensing anything peculiar about the exchange. So back in April, when the band announced the release of an upcoming EP, Persona, I didn’t think twice about mentioning to their publicist that I’d like to set something up. When he came back to tell me that Sami wasn’t doing any interviews, I was perplexed—and in the way that I tend to do, I somehow took that personally. But we just talked about it, I thought to myself. Did I do something wrong? As it turns out, I was doing the same thing that had been done to me. I’d made an assumption that Sami was a kind of person that they are not.

“Being in a band and being a frontperson has been a very opening experience for me, as far as branching outside of my mind and my social anxieties,” Sami explained to me, in a conversation that will be published in full on Thursday. “I’ve never been comfortable with perception—let alone on such a large scale, you know what I mean? It’s always been something I’ve struggled with.”

This was Sami’s first attempt at explaining how GEL’s newfound attention has forced them to reconsider their own sense of self—and how even becoming a singer in the first place began as a site of internal conflict.

“It was the beginning of Sick Shit,” Sami says, speaking of their first pre-GEL band. “There was an old singer, but things didn’t work out with him, and the band needed a singer. There was resistance on my end. But something clicked. I was like, ‘Wait. I want to do this. I can do this. This will be good for me to try to do this.’ So one day I went down to the basement of the house we were living in at the time in South Jersey and I put my headphones on. I had a cup of tea, a glass of wine, and a Monster [Energy Drink]. I had a bunch of beverages. And I just started screaming. I had to make sure no one was there. I didn’t want anyone to hear because I was cringing at myself and I didn’t want anyone else to cringe. I actually gave myself a nosebleed doing that, just from the stress and the buildup. But I just ripped the Band-Aid off and started going for it. And then I started writing words. Only a few weeks after doing that for the first time, we recorded fifteen songs in that same basement.”

For Sami, even doing this interview was a big step forward. It was a conscious attempt to adapt to the band’s currently developing situation, at a juncture when certain demands might be made of their time and attention in a way that feels counterintuitive to the kid in the basement who felt a release from screaming their head off, but whose anxiety almost didn’t allow anyone else to hear it. We sometimes take for granted the stereotype of the attention-hungry artist as an incontrovertible fact—so much so that it’s difficult to allow for the outliers, those of us who fell into our situations and discovered a joy in creation that we’re trying to hold onto in the face of a chasm between who we are and who we are expected to be.

III.

A couple of weeks ago, the pop star Chappell Roan wrote an open letter to her fans. It was a particularly honest letter about having to deal with what she called “predatory” or “superfan” behavior. It was about setting boundaries with her fans to protect her own safety and mental health. Her requests were not particularly entitled or egregious. “Please stop touching me,” she wrote. “Please stop being weird to my family and friends.” And yet much of the public response was still spiteful: “Chappell’s been famous for ten minutes and she’s moaning about her fans wanting a picture with her,” wrote one person on Twitter. “She doesn’t know being famous comes with lots of sacrifice?” asked another.

While the scale and culture attached to Chappell Roan’s experience is dissimilar to the scale and culture of the hardcore scene, I still recognize the response. Sometimes, even in our community, we can fail to treat each other as individuals with individual struggles. We can still treat the kids on the stage like they’re on the stage and not the floor. It’s in the way we refuse to give someone the benefit of the doubt when they make an honest mistake, rushing to shred them in the comments. It’s in the way we call someone “a rock star” if they come off short with an admirer, unwilling to consider what they might be personally going through that day. It’s in the way an artist can be made to feel guilty for sometimes having to prioritize their own mental health over the expectations of their audience. We, too, can be unkind.

Over the years, to do what I do, I’ve come to embrace ways of being that often feel at odds with my more natural inclinations. I’ve learned to be more outgoing, I’ve adjusted to being subject to critique, I’ve developed strategies to cope with some of the more awkward and occasionally unwanted social interactions that go along with the territory. But this kind of growth isn’t a one-way street. I’d like to think that we, as a community, can continue to reconsider our parasocial relationships with a more critical lens than, say, the fans of a pop singer. And I’d hope that we can find the compassion in knowing that none of us came to hardcore fully calloused from judgment and rejection. If people like me and Sami are still out there making things, it’s only because of a grace that has been extended to us—just enough, perhaps, to keep our anxieties at bay long enough to continue.

Coming on Thursday to Anti-Matter: A conversation with Sami Kaiser of GEL.

Anti-Matter is an ad-free, anti-algorithm, completely reader-supported publication—personally crafted and delivered with care. If you’ve valued reading this and you want to help keep it going, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. ✨

Thank you so much for this, Norman.

I sometimes joke that you are going to get sick of me because I am a particularly present fan, both of Antimatter and Thursday.

But to be serious for a rare moment, I believe that the relationship between artist and audience is one that should be built on mutual respect and understanding.

There are simple steps that fans can and should take to provide support for the artists they admire. Essentially: don’t be creepy and don’t make it weird (mileage may vary, everyone has different definitions, after all).

I think it’s important to minimize the time I take up during interactions so others get a chance to say hi, and so folks can get back to their jobs. At shows, I try to give back as much energy as I receive when the band is on stage.

Live music is a collaborative effort.

🖤

"...none of us came to hardcore fully calloused from judgment and rejection."

— Well said.